The Magic of Records

I love discovering fresh and exciting new music. But I often find myself fatigued in the search for it and end up putting on something older—usually Louis Armstrong or Gary Davis. After years of studying and trying my hand at music production and songwriting, my brain and ears are easily distracted dissecting these parts in new music. If nothing in a record really “grabs” me, I’m unable to listen passively. Instead, I’m listening for ideas and inspiration. I imagine that people working in film and TV have very similar experiences when watching movies and television.

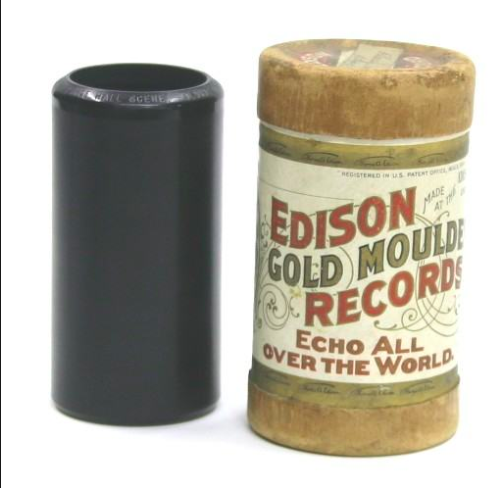

The reason older music doesn’t distract me as much isn’t because I think it’s better. Rather, it’s because the production is simple, and there is not much to dissect. Using audio technology to create records with complex auditory experiences has not always been the goal of record-makers, i.e., producers. The earliest recording we know of is a wax cylinder recording of “Au Clair de la Lune” from 1860. The record is one barely audible voice. At this point, audio recordings were literally a form of preservation—a record-keeping device.

Musical preservation has existed in many forms (including the folk revival of the 1960s and the many, many attempts made by Western anthropologists to “understand” African music), but the least retrospective of these was probably the blues recordings made in the 1920s and 30s. At this time in America, there was a huge effort to preserve the songs of the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia and other song-heavy regions, as one generation of musicians and storytellers died out, and a new era of recording technology was becoming the norm. After blues and folk came jazz recordings, which eventually led to bebop, and then (by no small force of culture, story-telling, and talent) rock came shortly after that.

Until rock, there wasn’t much anyone could do as a recording “engineer” beyond capturing the beauty of the music. There are stories about New Orleans big bands bunching together and taking turns getting closer to the single microphone for their solos during their recording sessions. For all intents and purposes, this process is a form of production but is simple compared to what was to come a short time after.

Music production can only be as complex as the technology available at the time. Thusly, we see music production shift as audio technology shifts and, like technology, exponentially. Reverb and other time-based effects, multi-tracking, amp distortion, compression as a creative tool, the speed and efficacy of computers in music production—in this shortlist we have traveled from the 1950s to today!

In trying to pinpoint the moment I started hearing production in music, the earliest memory I can find is hearing Neutral Milk Hotel’s In The Aeroplane Over The Sea. At the time I was playing guitar and singing in a band that had similar instruments that are on the album, including an accordion and saw. I had spent a little bit of time recording in a small studio outside of my small town, as a 15-year-old at-home dabbler of Garageband. The engineer, his assistant and I were re-recording four of my home demos (my guitar teacher had entered my recordings into a contest the studio was having, and I had unwittingly won the contest). I noticed how much time and effort it took to achieve a desired sound in the studio. We need to record the guitar part; are we plugging it directly into the computer? (Regarding guitars, the answer is almost always no.) Are we going to mic an amp in the big live room? Are we going to mic an amp in the isolation room? What amp are we going to use? What guitar are we going to use? How do we capture all the stuff we like about the demo, but somehow also make it better? And on and on for every sound.

The production played no small role in In The Aeroplane Over The Sea’s staying power. In the 21st century, there is a big difference between putting a microphone in a room and recording a band bunched up around it, and using multiple tracks, compression, vocal doubling, and arranging found sound noise to create an atmosphere that is reminiscent of a time and place, but isn’t literally a time or place (it’s a record). In The Aeroplane Over The Sea blends folk, noise and rock music and maintains a lo-fi quality, but is never messy or unprofessional. Also, it was not expected to be as popular as it was. The magic of this record is that the listener can experience the grittiness that songwriter and bandleader Jeff Mangum exhibited throughout all of his work and life, in the format of a record that sounds good to our ears.

The magic of records is that our ears are part of our culture, too. Even though most listeners of music are not trained in music production, their ears are discerning. They want a new perspective. They want something real. They want something fresh that can tell us a story about our world and lives.

So producers. Let’s make some magic records.

Editors Note: Folklorist Alan Lomax spent his career documenting folk music traditions from around the world. Now thousands of the songs and interviews he recorded are available for free online, many for the first time. It’s part of what Lomax envisioned for the collection — long before the age of the Internet.

Interview with Kelly Kramarik on How to Get Started

Interview with Kelly Kramarik on How to Get Started

On tour with Brittany Kiefer

On tour with Brittany Kiefer View from the Top: Maureen Droney, The Recording Academy

View from the Top: Maureen Droney, The Recording Academy