More Than Line-by-Line

Going Beyond the Basics of Mixing

When I started mixing shows in high school—and I use the term “mixing” loosely—I had no idea what I was doing. Which is normal for anyone’s first foray into a new subject, but the problem was that no one else knew either. My training was our TD basically saying, “here’s the board, plug this cable in here, and that’s the mute button,” before he had to rush off to put out another fire somewhere else.

Back then, there were no Youtube videos showing how other people mixed. No articles describing what a mixer’s job entailed. (Even if there were, I wouldn’t have known what terms to put in a Google search to find them!) So I muddled through show by show, and they sounded good enough that I kept going. From high school to a theme park, college shows to local community theatres, and finally eight years on tour, I’ve picked up a new tip or trick or philosophy every step along the way. After over a decade of trial and error, I’m hoping this post can be a jump start for someone else staring down the faders of a console wondering “okay, now what?”

Every sound design and system has a general set of goals for a musical: all the lines and music are clear and the level is enough to be audible but isn’t painfully loud. These parameters make a basic mix.

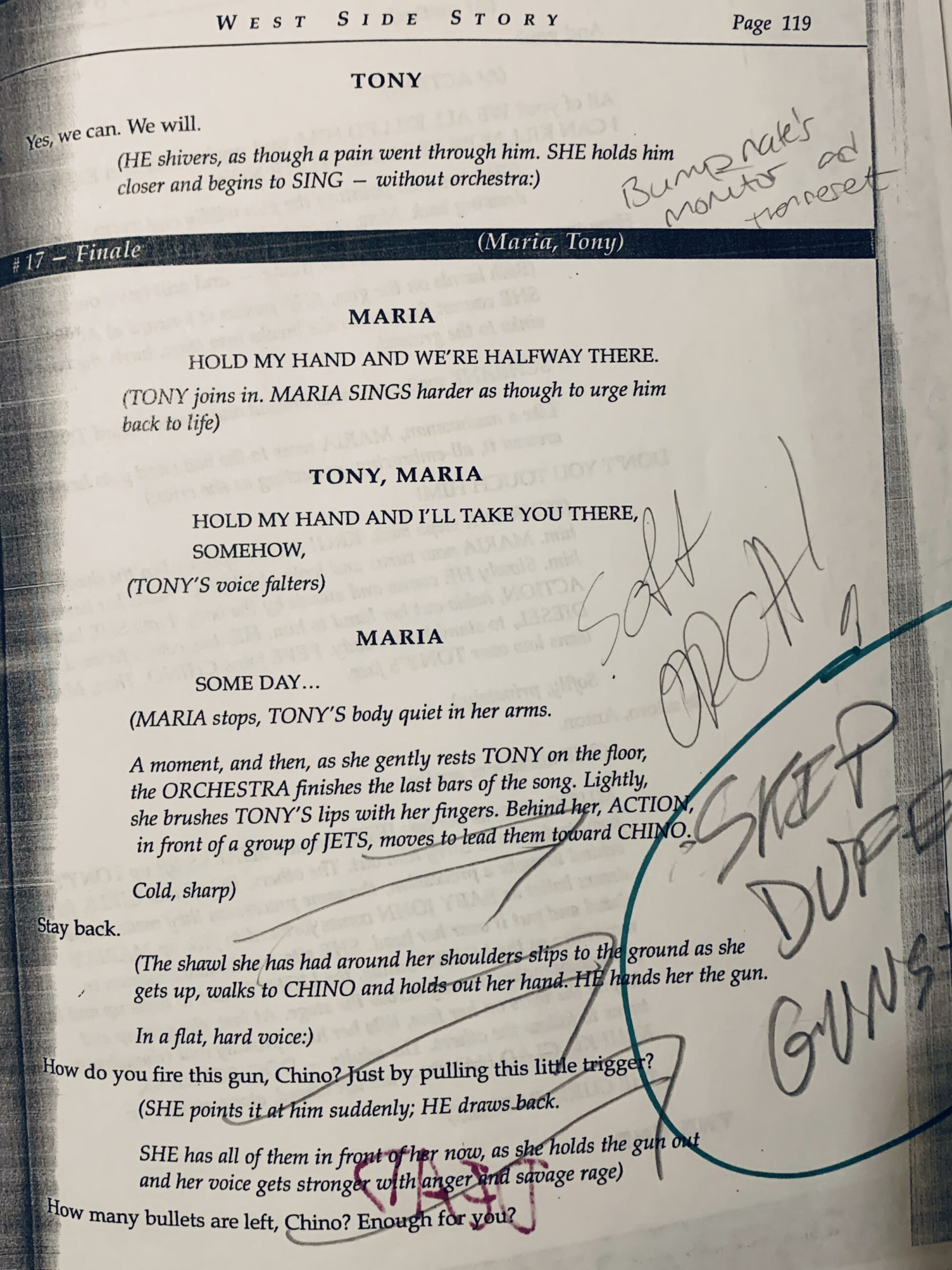

For Broadway-style musicals, we do what’s called “line-by-line” mixing. This means when someone is talking, her fader comes up and, when she’s done, her fader goes back down, effectively muting her. For example: if actresses A and B are talking, A’s fader is up for her line, then just before B is about to begin her line, B’s fader comes up and A’s fader goes down (once the first line is finished). So the mixer is constantly working throughout the show, bringing faders up and taking them out as actors start and stop talking. Each of these is called a “pickup” and there will be several hundred of them in most shows. Having only the mics open that are necessary for the immediate dialogue helps to eliminate excess noise from the system and prevent audio waves from multiple mics combining (creating phase cancellation or comb filtering which impairs clarity).

You may have noticed that I’ve only talked about using faders so far, and not mute buttons. Using faders allows you to have more control over the mix because the practice of “mixing” with mute buttons assumes that the actors will say each of their lines in the entire show at the same level, which is not realistic. From belting to whispering and everything in between, actors have a dynamic vocal range and faders are far more conducive than mute buttons to make detailed adjustments in the moment. However, when mixing with faders, you have to make sure that your movements are clean and concise. Constantly doing a slow slide into pickups sounds sloppy and may lose the first part of a line, so faders should be brought up and down quickly. (Unless a slow push is an effect or there is a specific reason for it, yes, there are always exceptions.)

So, throughout the show, the mixer is bringing faders up and down for lines, making small adjustments within lines to make sure that the sound of the show is consistent with the design. Yet, that’s only one part of a musical. The other is, obviously, the music. Here the same rules apply. Usually, the band or orchestra is assigned to VCAs or grouped so it’s controlled by one or two faders. When they’re not playing, the faders should be down, and when they are, the mixer is making adjustments with the faders to make sure they stay at the correct level.

The thing to remember at this point is that all these things are happening at the same time. You’re mixing line by line, balancing actor levels with the music, making sure everything stays in an audible, but not eardrum-ripping range. This is the point where you’ve achieved the basic mechanics and can produce an adequate mix. When put into action, it looks something like this:

A clip from a mix training video for the 2019 National Touring Company of Miss Saigon.

But we want more than just an adequate mix, and with a solid foundation under your belt, you can start to focus on the details and subtleties that will continue to improve those skills. Now, full disclosure, I was a complete nerd when I was young (I say that like I’m not now…) and I spent the better part of my childhood reading any book I could get my hands on. As an adult, that has translated into one of my greatest strengths as a mixer: I get stories. Understanding the narrative and emotions of a scene are what help me make intelligent choices of how to manipulate the sound of a show to best convey the story.

Sometimes it’s leaving an actress’s mic up for an ad-lib that has become a routine, or conversely, taking a mic out quicker because that ad-lib pulls your attention from more important information. It could be fading in or out a mic so that an entrance or exit sounds more natural or giving a punchline just a bit of a push to make sure that the audience hears it clearly.

Throughout the entire show, you are using your judgment to shape the sound. Paying attention to what’s going on and the choices the actors are making will help you match the emotion of a scene. Ominous fury and unadulterated rage are both anger. A low chuckle and an earsplitting cackle are both laughs. However, each one sounds completely different. As the mixer, you can give the orchestra an extra push as they swell into an emotional moment, or support an actress enough so that her whisper is audible through the entire house but doesn’t lose its intimacy.

Currently, I’m touring with Mean Girls, and towards the end of the show, Ms. Norbury (the Tina Fey character for those familiar with the movie) gets to cut loose and belt out a solo. Usually, this gets some appreciative cheers from the audience because it’s Norbury’s first time singing and she gets to just GO for it. As the mixer, I help her along by giving her an extra nudge on the fader, but I also give some assistance beforehand. The main character, Cady, sings right before her in a softer, contemplative moment and I keep her mic back just a bit. You can still hear her clearly, but she’s on the quieter side, which gives Norbury an additional edge when she comes in, contrasting Cady’s lyrics with a powerful belt.

Another of my favorite mixing moments is from the Les Mis tour I was on a couple of years ago. During “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables,” Marius is surrounded by the ghosts of his friends who toast him with flickering candles while he mourns their seemingly pointless deaths. The song’s climax comes on the line “Oh my friends, my friends, don’t ask me—” where three things happen at once: the orchestra hits the crest of their crescendo, Marius bites out the sibilant “sk” of “don’t aSK me,” and the student revolutionaries blow out their candles, turning to leave him for good. It’s a stunning visual on its own, but with a little help from the mixer to push into both the orchestral and vocal build, it’s a powerful aural moment as well.

The final and most important part of any mix is: listening. It’s ironic—but maybe unsurprising—that we constantly have to remind ourselves to do the most basic aspect of our job amidst the chaos of all the mechanics. A mix can be technically perfect and still lack heart. It can catch every detail and, in doing so, lose the original story in a sea of noise. It’s a fine line to walk and everyone (and I mean everyone) has an opinion about sound. So, as you hit every pickup, balance everything together, and facilitate the emotions of a scene, make sure you listen to how everything comes together. Pull back the trumpet that decided to go too loud and proud today and is sticking out of the mix. Give the actress who’s getting buried a little push to get her out over the orchestra. When the song reaches its last note and there’s nothing you need to do to help it along, step back and let it resolve.

Combining all these elements should give you a head start on a mix that not only achieves the basic goals of sound design but goes above and beyond to help tell the story. Trust your ears, listen to your designer, and have fun mixing!

We just got some new merch in. Long Sleeves, Onesies, Toddlers, Gig Bags, and Canvas Totes. Check it out Here

We just got some new merch in. Long Sleeves, Onesies, Toddlers, Gig Bags, and Canvas Totes. Check it out Here