Finding that Job

As I see postings online from people asking for advice about how to start their careers just out of school or how to change their careers to join the audio world, it makes me think about the job hiring process and changes I went through about a year ago. It had been a while coming. I knew I was ready for a change, but I was waiting for the right change through finding the right job. Looking back, I’m not sure if finding the right position was the proper way to look as much as something that would be different and would challenge me, but also keep me engaged while learning new things. Overall, looking back I think I learned the most during the interview processes I went through followed by actually moving and experiencing all the change.

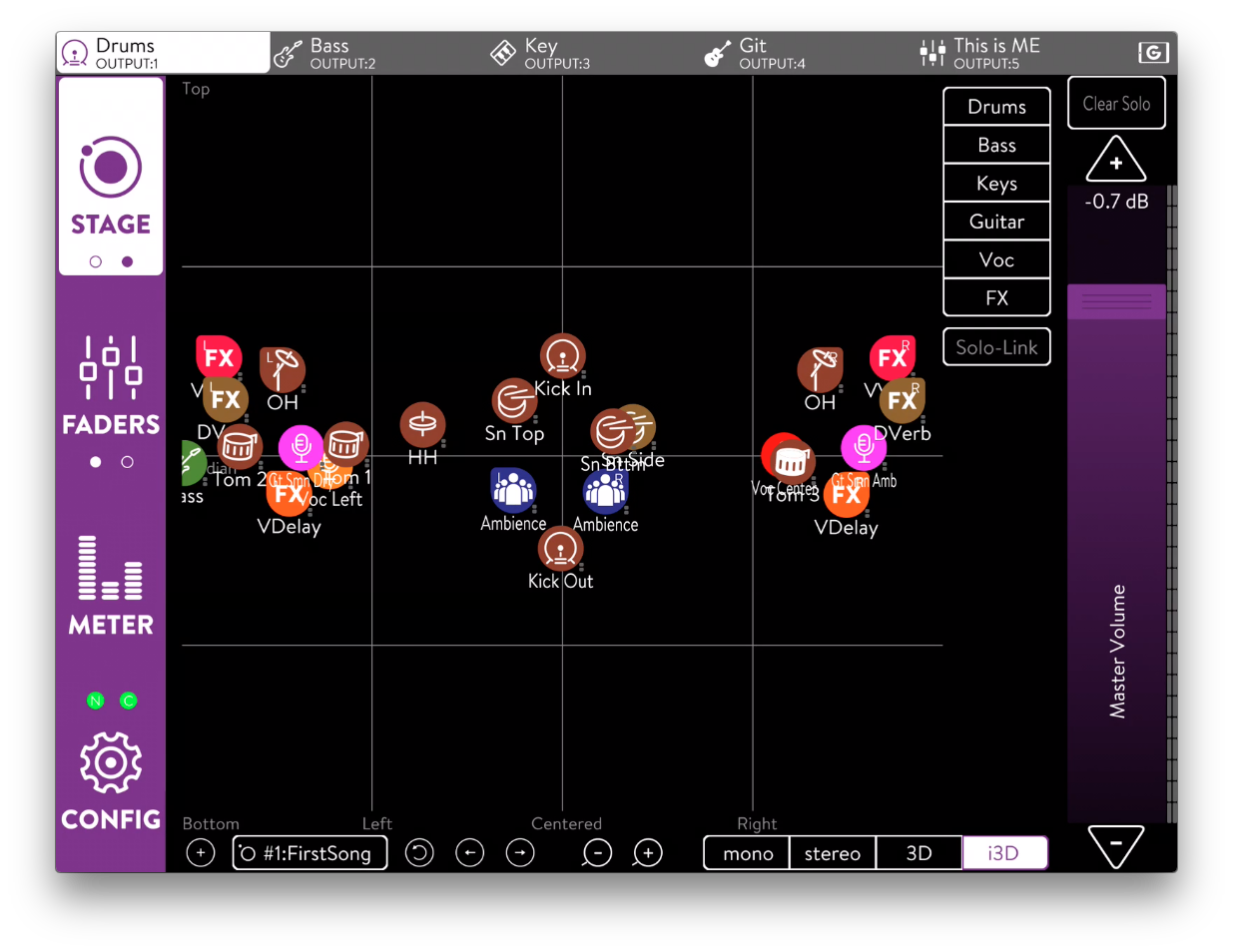

Once I made my choice about wanting to move, I then had to search for a new job. Using all the popular sites, I found it wasn’t that straightforward to find the kind of job I was looking for. In our industry, we use a unique language to get our work done. Hiring managers and job boards don’t necessarily understand that language either. Yes, there are job boards out there just for our industry, but there are many entities hiring that won’t use those boards because it is too specific to the industry for the 1 or 2 positions they have. The corporate environment will either use a recruiter to get down into an intricate area of a specific industry or will hope the keywords match on a large job board site. As you start your search, get creative with the job title words you search for. A venue manager may be listed under Facilities Coordinator, or A1 could be listed as Technician.

You will likely apply for a lot of jobs. Don’t just apply for one at a time, apply for all the jobs that interest you and that you are qualified for. Response rates can be slow, and you don’t want to waste valuable time and good opportunities hoping you will hear from one specific place. You could miss out on better opportunities. You could also miss out on valuable experience interviewing too. During the interview is where you will learn most about the organization and their expectations for you and the position. They will spend a majority of the time talking to you about your qualifications to see how you will fit in their world, but it is also ok for you to ask questions to see if you will fit in their world too. More than just skills need for a job; you need to determine if you can work for them. We spend a lot of our lives working, so I advise making sure you work for an entity that you are willing to spend a lot of your life at.

As you apply to different jobs, I recommend keeping a copy of the job description as well as the cover letter and resume you submitted. This way if you do get an interview you will have a copy of the resources you provided them since they should be tailored for that specific application.

As you are interviewing watch for the positive and negatives of the organization. Ask strategic questions regarding the research you have done on the organization and learn as much as you can to make a decision later on. Some red flags to watch for are how they communicate with you before, during, and after the interview. Is it concise communication or are they sending you mixed messages? Do they call you back when they say they will? Does the hiring manager or person who greets you at the start of the interview speak positively about the organization and the environment they work in?

Watch for the red flags like managers telling you just a little too much about the organization’s dysfunction or personal information about possible future co-workers. Dodging the questions you’re asking, or interviewing a couple of times with the same person only to learn you have two or three more interview steps to go that will be scheduled over the next few weeks. Be cautious of interviews that are continuously scheduled with the same person over and over. This may be a sign the organization is not ready to hire someone, or that management is not genuinely interested in you. Don’t forget to ask about their timeline to complete the hiring process too.

I went on one interview last year where there were some red flags when they asked me what I did with downtime during work hours, and how I would handle a continuously light schedule. I answered as clearly as I could, but couldn’t help but wonder – Am I going to be bored working here? Will there be a challenge for me? During that same interview, a staff member also shared with me the ‘drama’ within the department. There will always be differences among co-workers, but if that’s shared during the interview process, it should make you wonder how much ‘drama’ is happening on a daily basis. They also shared how the organization did not support the department, which was surprising to hear. Those were all signs that working in that environment would not have been for me. So when the job offer came, I knew the job wasn’t for me.

On the other hand, watch for the positive signs such as a hiring process that is well organized, welcoming, and that you get a great vibe while you are going through the process. They provide precise information about, organization and the job in which you are interviewing for. In my opinion, the interview process should feel good, maybe a little nerve-wracking while in the process, but good afterward. Be prepared for many different kinds of approaches as you may work with recruiters or hiring managers, but you could also be talking directly with the president or owner as well. Expect multiple steps to the interview like a video or phone interview first, a general interview second, then maybe a management interview to finish the process.

Then if you’re right for them and it’s right for you get ready for your next adventure! Starting a new job can be significant and scary at the same time. No matter what it will be a great experience to add to your tool belt. Also, remember as you get your first or second job within the audio or events world, remember all of us SoundGirls are here to help along the way!

Interview with Kelly Kramarik on How to Get Started

Interview with Kelly Kramarik on How to Get Started