This month’s blog will go over some basic music theory concepts that I have found useful in my work as a musical theatre mixer. Full credit for the title goes to Professor Thomas W. Douglas of Carnegie Mellon University, who taught a class by that name when I was an undergrad. I know that not everyone working in theatrical sound has a formal music education (and I am not suggesting that it’s a requirement) but I think that being able to understand what is going on in a score, follow along in the music, and in some cases, line-by-line mix from the score, are good skills for anyone in this field to have.

Part 1: From the Top

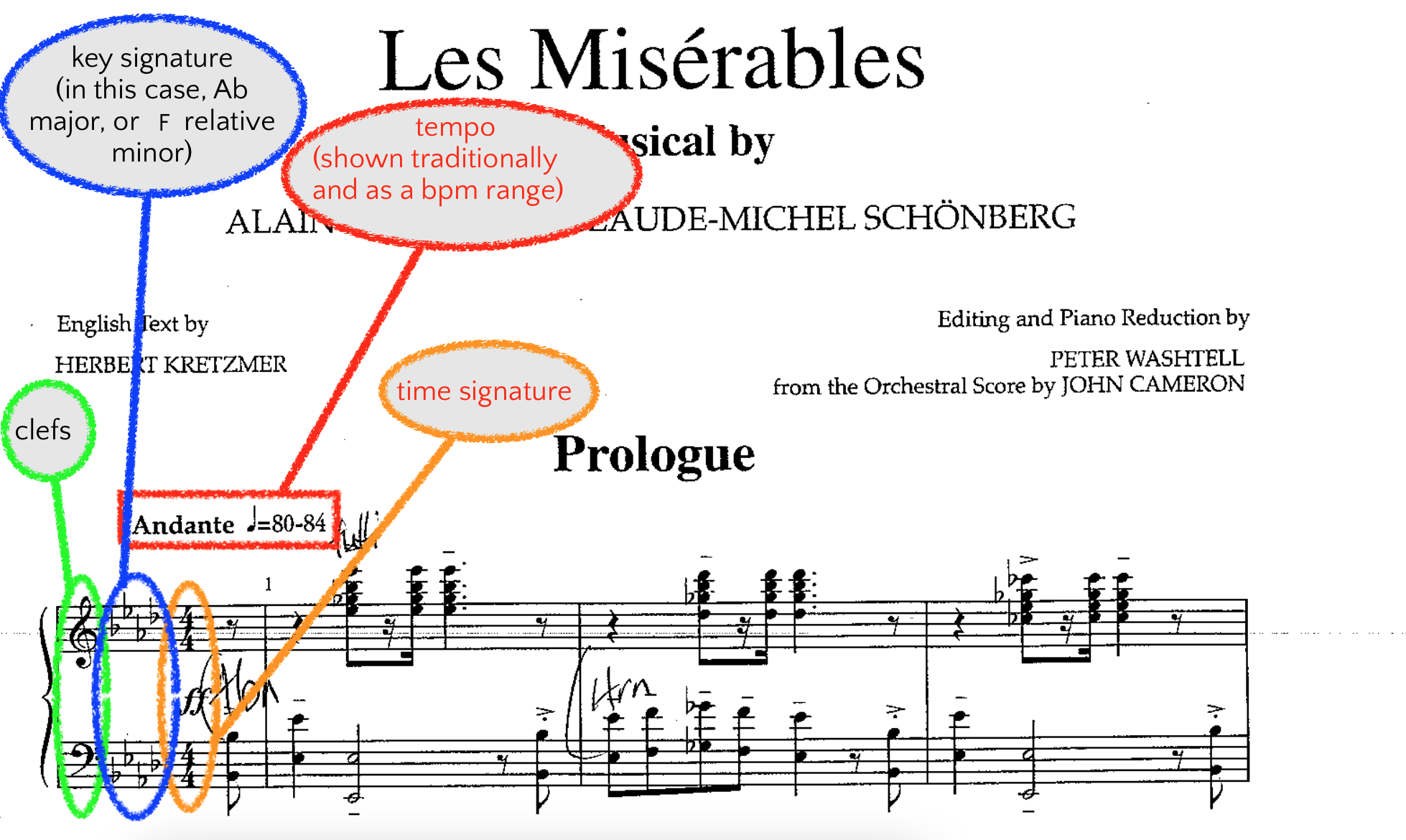

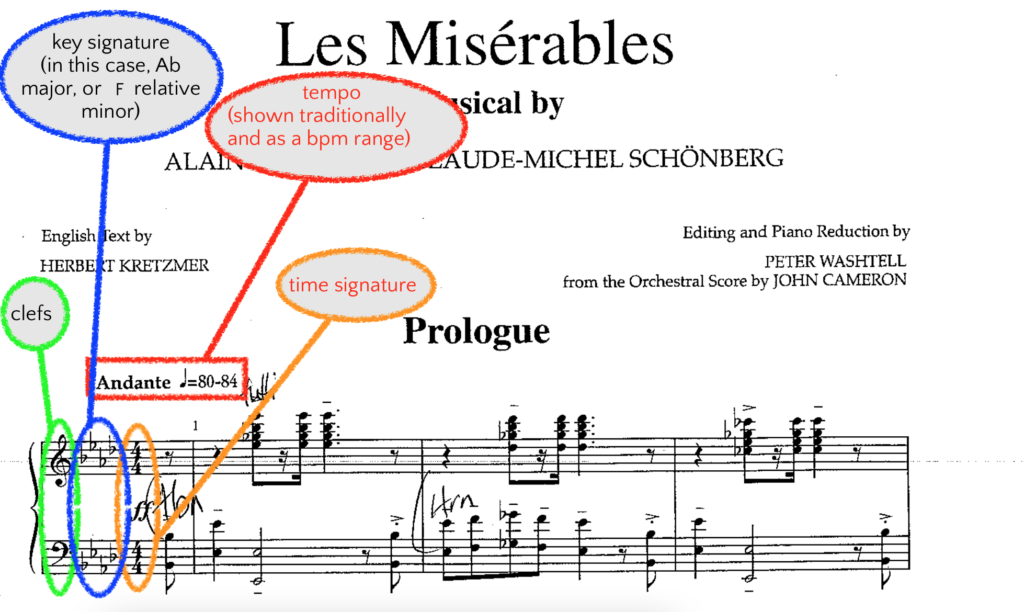

As with any piece of writing, the most important information about a score is at the top of the page. This first set of symbols gives you a roadmap for what the song should sound like and how it should feel when played. Some of that basic information includes:

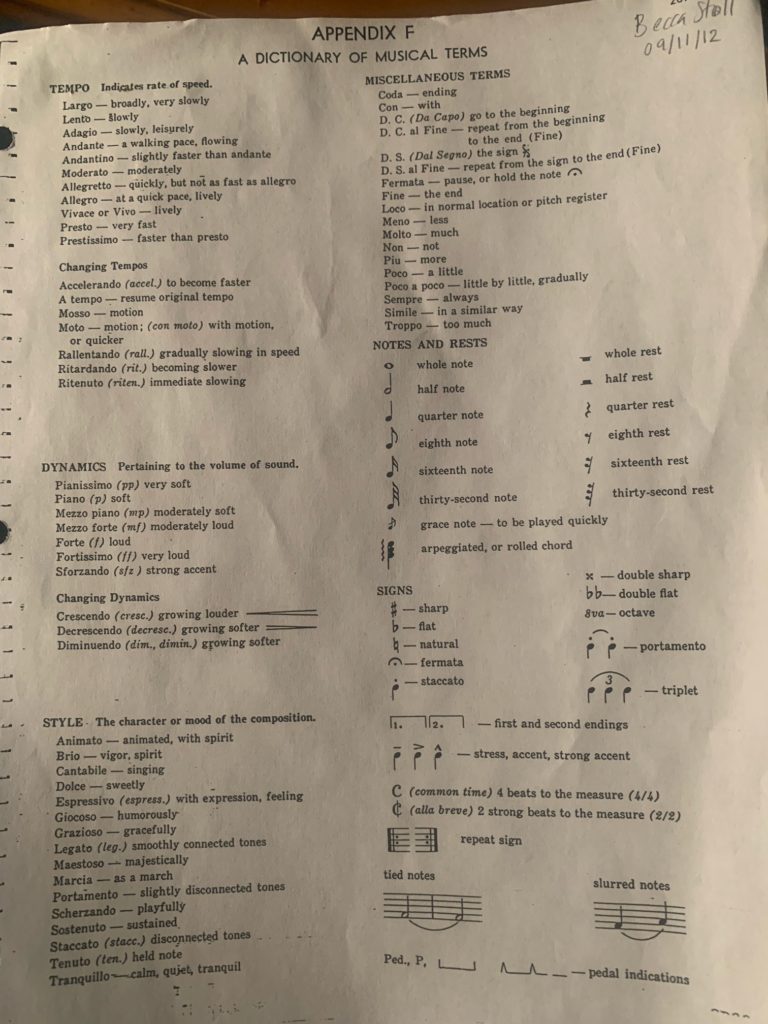

Tempo: the “speed” of a song. Sometimes delineated in Italian terms ranging from the slowest (largo) to fastest (prestissimo). Often in modern shows, and especially new musicals, you will see more descriptive tempo terms such as “steady rock beat” or “upbeat.” Some of the tempo descriptions for the new musical I am currently mixing include “bluesy protest song,” “Dylanesque,” “pop 4,” “feverish,” and my personal favorite, “Tempo di ‘Four Seasons.’” Also common in modern and new musicals is a specific bpm marking, e.g., “quarter note = 120.” This is often included even on songs that aren’t played to a click, just to give a specific sense of how the tune should feel.

Time signature: the “meter” of the song. Shown as two stacked numbers, with the top number representing the number of beats in a measure (or bar) of music, and the bottom one showing what note counts as 1 beat. So, in 4/4 time, 4 quarter notes, or any other combination of notes adding up to 4 quarter notes (such as 2 half notes), makes 1 bar of music. Since 4/4 is overwhelmingly the most common time signature, it is often abbreviated by just writing a “C” for “common time.” Additionally, time changes within the same song are more common in show tunes than in pop music, as they can be helpful ways to revisit motifs from previous songs or highlight a shift in plot, mood, or tension.

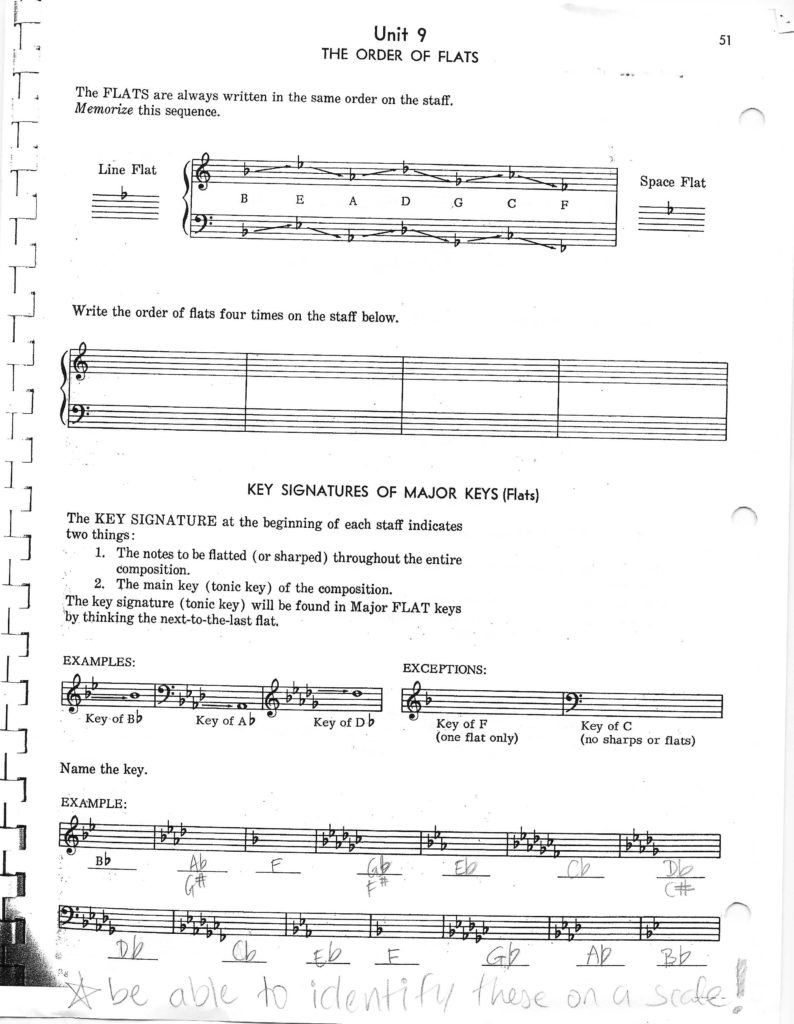

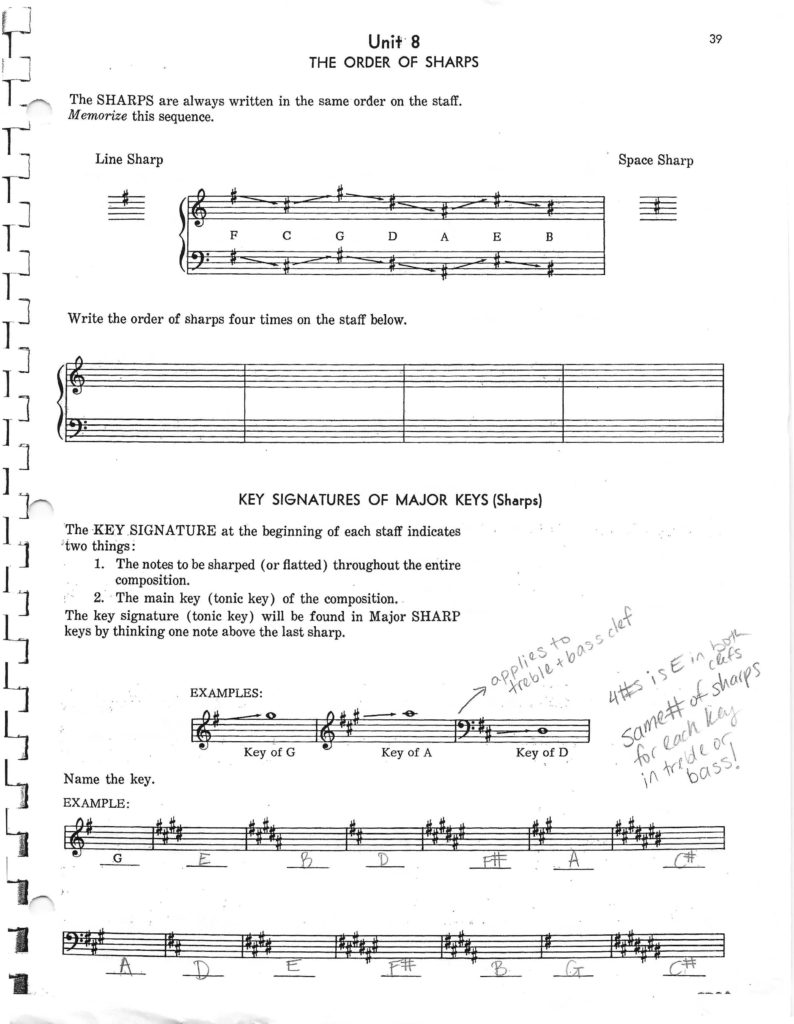

Key signature: what “scale” the piece is in (or at least, much like tempo and time signature, what key the song starts in.) A good way to learn key signatures is by studying the “Circle of Fifths” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circle_of_fifths), and learning the shortcuts to analyzing sharps and flats to quickly discern a key. The “signs” section in the graphic above shows the symbols for sharp, flat, and natural.

- Some basics about key signatures. Courtesy of Thomas W. Douglas.

- Some basics about key signatures. Courtesy of Thomas W. Douglas.

Clefs: what note range this part is written in. Most vocal parts for musical theatre are written in treble clef or G clef. A piano-vocal score (or PV) for a show will have the vocal lines in treble clef (sometimes with bass parts shown in treble clef 8vb, meaning that the notes are written in treble clef but should be sung down an octave), and then treble and bass clef lines for the piano part.

Part 2: Following Along in a Score

While plenty of music, both classical and pop, contains a common set of musical conventions, there are some things that I specifically look for when analyzing a musical theatre score. Some of those things are:

Repeats, Codas, Vamps, and Safeties

Repeats are exactly what they sound like: a section of music played through twice (or more times if indicated, but always a specific number of times). See the above glossary for a picture of the repeat symbols in music notation. Repeats can be useful when a song has a clear verse and chorus that are melodically identical, therefore the copyist can just write them into the music once (with both sets of lyrics under the vocal line) and delineate the first and second endings instead of writing the whole figure out twice.

Another thing that repeats allow for is Codas. A coda is the “tail” of a piece and is only played the last time through a repeated piece. When a piece of music says “D.C al Coda” this means “play the piece through as many times as the repeats indicate, but on the final time through, skip ahead to the Coda where the music indicates to do so.” Coda markings look kind of like a set of crosshairs and are often accompanied by the words “to coda” or “al coda”.

What about vamps? Romanbenedict.com defines a vamp as “a section of music that is repeated several times while dialogue or onstage action occurs. It is usually directed by the conductor’s cue, and as such can cope with the unpredictability of long stretches of dialogue or indeterminable theatrical machinations.” Vamps might be used when a song has a scene break in the middle of it because, while an 8-bar section of music always takes roughly the same amount of time to play, the pacing of the script (or the speed of a scenic transition) is not so precisely timed and may vary in length from night to night. The cue to move out of the vamp could be a certain line of dialogue or a scene change completing and will be clearly cued by the music director. It’s good to know where the vamps are in a musical number so that you can keep track of where you are in the song and not accidentally miss a pickup, band move, or a snapshot.

Safeties can be thought of as “optional” vamps, meaning that they could be played or skipped entirely based on timing variations from performance to performance.

Dynamics: Dynamics, as we learn in audio, are variations in loudness. Similarly, in music, dynamic descriptions tell us where this piece of music lands on the soft-to-loud, or in this case, “piano” to “forte” spectrum. In scores, you will find dynamics abbreviated using p for “piano” aka soft, f for “forte” aka loud, and m for “mezzo” or moderately (used in combination with p or f such as mp or mf).

Changes in dynamics: the Italian terms for these are crescendo and decrescendo. A crescendo is a gradual increase in volume and decrescendo means a gradual decrease. They are written either as the abbreviation “cresc.” Or, more commonly, by putting an elongated “<” or >” symbol under the bars of music encompassing the duration of the dynamic shift. There may also be an indication of what dynamic you are moving to or from (such as p<f, meaning crescendo from piano to forte), but this is optional. Crescendo markings are one of my favorite shorthand symbols to use in my mix scripts, so rather than write out “fade band up to -8” I will simply write “B<-8”. I also often use crescendo markings at the end of songs to indicate a big band build, or decrescendo markings on the first lyric after the intro to indicate a small band decrease when the vocal starts.

Changes in tempo: there are a lot of Italian terms for slowing a tempo down; the most common one is ritardando, often abbreviated as “rit.” Other terms include rallantando (rall. for short), or “moso” which means movement, and can have further elaboration such as piu moso (a little faster) or meno moso (a little slower).

Key changes: also called modulations. These can be everywhere in musical theatre but are most common in the final verse of a song, where the music and action take a big emotional shift. You will know there is a key change because in the middle of the music there will be a new key signature that now supersedes the original key for the remainder of the song (until you get to the next key change).

Rubato: this means played freely, without a clear tempo.

Fermata: a long-held note, often at the end of a song as part of the “big finish.”

Button: Buttons aren’t necessarily explicitly defined in the music, but they’re hard to miss. A clean, 1-beat ending to a song. Here is a great thread from Lin-Manuel Miranda explaining the emotional intent of buttons and why some songs do or don’t have them: https://twitter.com/lin_manuel/status/951215051633037312

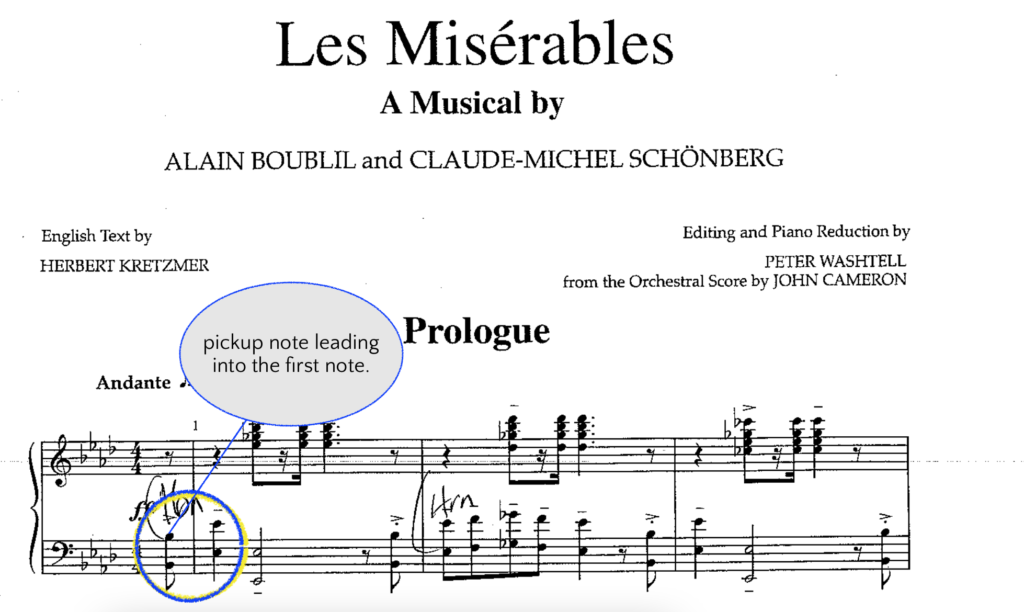

Pickup note(s): this is when a song begins with an incomplete measure of music. For an example of a pickup, we can revisit the opening of Les Misérables which I dissected in part 1. The song begins with an eighth-note pickup, such that melodically the music starts on the “and” of the 4th beat of the 0th measure.

Part 3: Putting it together

Now armed with the tools to read a score more clearly, the next step is to apply your music theory in action as a mixer!

When should you opt to mix using a PV instead of a script? The answer is “it depends.” Also, the decision to mix from a score does not have to be universal but can be decided on a song-by-song basis.

There are many reasons to use score or not, such as personal preference, designer preference, lack of access to an updated or well-formatted script, and many more. But basically, as always, it comes down to picking the best tool for the job, the job in this case mixing this number of the musical.

So, for a real-world case study, here are some example PV pages for “Finale Ultimo” from my mix script for The Drowsy Chaperone, which I chose to mix on the score for ease of clarity in making the pickups for the layered vocal parts that flow in and out as the main character, The Man in the Chair, sings the melody. This section of PV matches up to approximately 0:30-1:39 in the recording from the cast album linked below.

I hope this blog has made you a little more musically “street-smart” and as always, feel free to reach out to me with any questions or suggestions for future blog topics!