Whether you’re mixing for film in 5.1 surround or Dolby Atmos, it’s important to consider a key element of human auditory perception: localization. Localization is the process by which we identify the source of a sound. We may not realize it, but each time we sit down to watch a movie or TV show, our brains are keeping track of where the sound elements are coming from or headed towards, like spaceships flying overhead, or an army of horses charging in the distance. It is part of the mixer’s role to blend the auditory environment of a show so that listeners can accurately process the location of sounds without distraction or confusion. Here are some psycho-acoustical cues to consider when mixing spatial audio.

ILDs and ITDs, What’s The Difference?

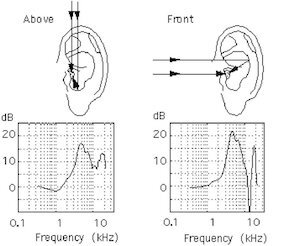

Because we primarily listen binaurally or, with two ears, much of localization comes from interaural level and time differences. Interaural level differences depend on the variations in sound pressure from the source to each ear, while interaural time differences occur when a sound source does not arrive at each ear at the same time. These are subtle differences, but the size and shape of our heads impacts how these cues differ between high and low frequencies. Higher frequencies with shorter wavelengths can move around our heads to reach our ears, causing differences in sound pressure levels between each ear, and allowing us to determine the source’s location. However, lower frequencies with larger wavelengths are not impacted by our heads in the same way, so we depend on interaural time differences to locate low frequencies instead. Although levels and panning are great tools for replicating our perception of high frequencies in space, mixers can take advantage of these cues with mixing low end too, which we usually experience as engulfing the space around us. A simple adjustment to a low-end element with a short 15-40 millisecond delay can make a subtle change to that element’s location, and offer more space for simultaneous elements like dialogue.

Here is a visualization of how high and low frequencies are impacted by the head.

Flying High

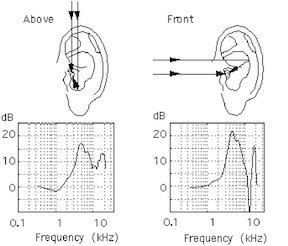

While a lot of auditory perception occurs inside the ear and brain, the outer ear has its own way of affecting our ability to locate sounds. For humans and many animals, the pinna defines the ridges of the human ear that are visible to the eye. Although pinnae are shaped differently for each individual, the function remains the same: it acts as a high-pass filter that tells the listener how high a sound is above them. When mixing sound elements in an immersive environment to seem like they are above the head, emphasizing any frequencies above 8000 Hz with an EQ or high-shelf can more accurately emulate how we experience elevation in the real world. Making these adjustments along with panning the elevation can make a bird really feel like it’s chirping above us in a scene.

See how the pinna acts as a “filter” for high frequencies arriving laterally versus elevated.

The Cone of Confusion

A psycho-acoustical limitation to avoid occurs at the “cone of confusion,” an imaginary cone causing two sound sources that are equidistant to both ears to become more difficult to locate. In a mix, it is important to consider this when two sounds might be coming from different locations at the same time and distance. While it’s an easy mistake to make, there are a handful of steps to overcome the cone of confusion and designate one sound element as being farther away, including a simple change in level, using a low-pass filter to dull more present frequencies in one sound, or adjusting the pre-delay to differ between the two sounds.

This demonstrates where problems can occur when locating two equidistant sound sources.

With these considerations, mixers can maintain the integrity of our auditory perception and make a film’s sound feel even more immersive.

Written by Zanne Hanna

Office Manager, Boom Box Post

This blog originally was published on Boom Box Post