Modulation is still an impactful tool in Pop music, even though it has been around for centuries. There are a number of well-known key changes in many successful Pop songs of recent musical decades. Modulation like a lot of tonal harmonies involves tension and resolution: we take a few uneasy steps towards the new key and then we settle into it. I find that 21st-century modulation serves as more of a production technique than the compositional technique it served in early Western European art music (this is a conversation for another day…).

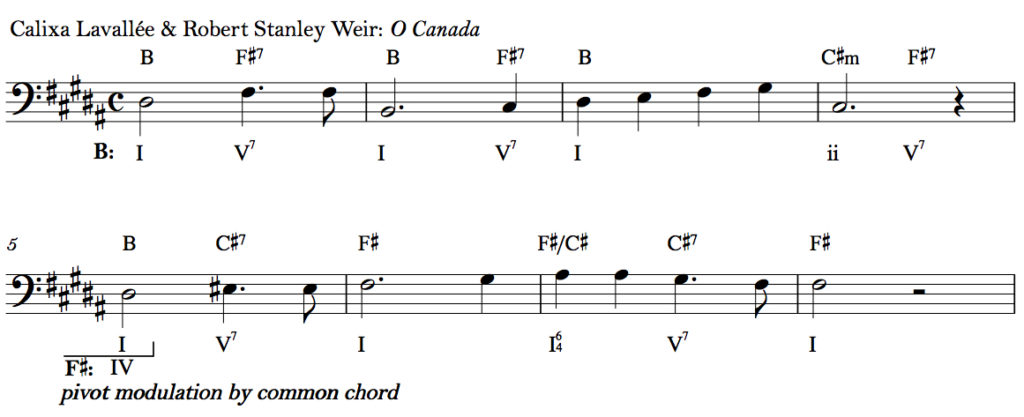

Example of modulation where the same chord exists in both keys with different functions.

Nowadays, it often occurs at the start of the final chorus of a song to support a Fibonacci Sequence and mark a dynamic transformation in the story of the song. Although more recent key changes feel like a gimmick, they are still relatively effective and seem to work just fine. However, instead of exploring modern modulation from the perspective of music theory, I want to look into two specific concepts in psychoacoustics: critical bands and auditory scene analysis, and how they are working in two songs with memorable key changes: “Livin’ On A Prayer” by Bon Jovi and “Golden Lady” by Stevie Wonder.

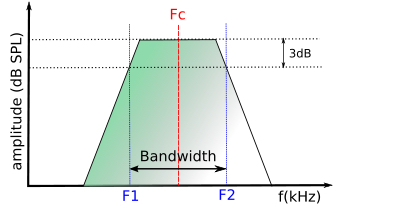

Consonant and dissonant relationships in music are represented mathematically as integer-ratios; however, we also experience consonance and dissonance as neurological sensations. To summarize, when a sound enters our inner ear, a mechanism called the basilar membrane response by oscillating at different locations along the membrane. This mapping process called tonotopicity is maintained in the auditory nerve bundle and essentially helps us identify frequency information. The frequency information devised by the inner ear is organized through auditory filtering that works as a series of band-pass filters, forming critical bands that distinguish the relationships between simultaneous frequencies. To review, two frequencies that are within the same critical band are experienced as “sensory dissonant,” while two frequencies in separate critical bands are experienced as “sensory consonant.” This is a very generalized version of this theory, but it essentially describes how frequencies in nearby harmonics like minor seconds and tritones are interfering with each other in the same critical band, causing frequency masking and roughness.

Depiction of two frequencies in the same critical bandwidth.

Let’s take a quick look at some important critical bands during the modulation in “Livin’ On A Prayer.” This song is in the key of G (392 Hz at G4) but changes at the final chorus to the key of Bb (466 Hz at Bb4). There are a few things to note in the lead sheet here. The key change is a difference of three semitones, and the tonic notes of both keys are in different critical bands, with G in band 4 (300-400 Hz) and Bb in band 5 (400-510 Hz). Additionally, the chord leading into the key change is D major (293 Hz at D4) with D4 in band 3 (200-300 Hz). Musically, D major’s strongest relationship to the key of Bb is that it is the dominant chord of G, the minor sixth in the key of Bb. Its placement makes sense because previously the chorus starts on the minor sixth in the key of G, which is E minor. Even though it has a weaker relationship to Bb major which kicks off the last chorus, D4 and Bb4 are in different critical bands and if played together would function as a major third and create sensory consonance. Other notes in those chords are in the same critical band: F4 is 349 Hz and F#4 is 370 Hz, placing both frequencies in band 4 and if played together would function as a minor second and cause sensory roughness. There are a lot of perceptual changes in this modulation, and while breaking down critical bands doesn’t necessarily reveal what makes this key change so memorable, it does provide an interesting perspective.

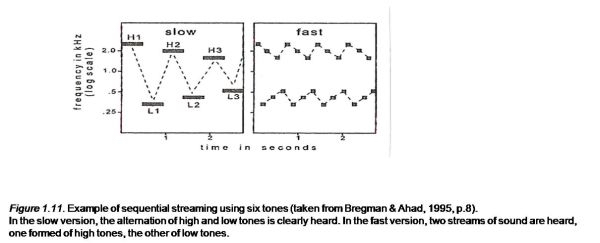

A key change is more than just consonant and dissonant relationships though, and the context provided around the modulation gives us a lot of information about what to expect. This relates to another psychoacoustics concept called auditory scene analysis which describes how we perceive auditory changes in our environment. There are a lot of different elements to auditory scene analysis including attention feedback, localization of sound sources, and grouping by frequency proximity, that all contribute to how we respond to and understand acoustical cues. I’m focusing on the grouping aspect because it offers information on how we follow harmonic changes over time. Many Gestalt principles like proximity and good continuation help us group frequencies that are similar in tone, near each other, or serve our expectations of what’s to come based on what has already happened. For example, when a stream of high notes and low notes is played at a fast tempo, their proximity to each other in time is prioritized, and we hear one stream of tones. However, as this stream slows down, the value in proximity shifts from the closeness in timing to the closeness in pitch, and two streams of different high pitches and low pitches are heard.

Demonstration of “fission” of two streams of notes based on pitch and tempo.

Let’s look at these principles through the lens of “Golden Lady” which has a lot of modulation at the end of the song. As the song refrains about every eight measures, the key changes by a half-step or semitone upwards to the next adjacent key. This occurs quite a few times, and each time the last chord in each key before the modulation is the parallel major seventh of the upcoming minor key. While the modulation is moving upwards by half steps, however, the melody in the song is moving generally downwards by half steps, opposing the direction of the key changes. Even though there are a lot of changes and combating movements happening at this point in the song, we’re able to follow along because we have eight measures to settle into each new key. The grouping priority is on the frequency proximity occurring in the melody rather than the timing of the key changes, making it easier to follow. Furthermore, because there are multiple key changes, the principle of “good continuation” helps us anticipate the next modulation within the context of the song and the experience of the previous modulation. Again, auditory scene analysis doesn’t directly explain every reason for how modulation works in this song, but it gives us ulterior insight into how we’re absorbing the harmonic changes in the music.