Aspectos básicos sobre una mezcla de sonido en vivo

Para realizar sonorizaciones en vivo, es de suma importancia saber utilizar múltiples equipos relacionados con el sonido, así como tener claro el flujo de trabajo de los aparatos que utilizamos para trabajar. El tener conocimientos teóricos sobre los fundamentos del sonido, acústica, flujos de señal, nos ayudará a entender mucho mejor el proceso de realización de una mezcla para sonido en vivo. También debemos tener claros conceptos como estructura de ganancia, saber cómo funcionan los procesadores de frecuencia, dinámica, tiempo y dedicar mucho tiempo a cuestiones relacionadas con la fase, el diseño y la optimización de sistemas. Y, sin embargo, en ocasiones, nos olvidamos de lo fundamental: La Mezcla.

Introducción a la mezcla.

En grabaciones de estudio, la mezcla es un factor importantísimo (evidente: primero grabamos y luego mezclamos). Pero en las sonorizaciones en vivo, en ocasiones, se pierde un poco la perspectiva: Diseñamos el sistema de sonido, hacemos predicciones, se monta, se optimiza, se instala el monitoreo, se posicionan los micrófonos elegidos cuidadosamente, se hace el show y desmontamos.

Algo tan sencillo de decir como “hacer el show” o “sonorizar el concierto” es, realmente, un proceso de mezcla muy complejo que, como todo, se debe de aprender a desarrollar. Además, hay que aprender a hacer la mezcla rápidamente, pues las pruebas de sonido en vivo tienden a ser rápidas.

En estudio, podemos llegar a tener cierto margen de horario para completar la mezcla (en ocasiones, en el estudio, si no nos encontramos con el día inspirado, podemos cancelar la sesión y seguir mezclando en otro momento). Pero en el vivo no hay segundas oportunidades: hay que sacarlo adelante sí o sí.

Evidentemente, todos los conocimientos que hemos nombrado al principio del blog nos van a ayudar a hacer la mezcla (si no sabemos cómo funcionan nuestras herramientas, no conocemos los principios básicos del sonido y no tenemos el sistema bien ajustado, sería difícil sacar la mezcla adelante). Pero cuando nos ponemos frente la consola y tenemos al talento en el escenario, tenemos que ser capaces de responder a la siguiente pregunta: ¿Cómo debe sonar?, aquí entran en juego múltiples cuestiones.

La primera es que las mezclas son una cuestión subjetiva. Pon a 100 ingenieros de sonido a mezclar al mismo grupo y tendrás 100 mezclas diferentes. Algunas te gustarán más y otras menos, pero seguramente todas serán válidas, al menos para el que la ha realizado.

En un concierto con mucho público es complicado satisfacer el criterio de mezcla de todos los espectadores. Pero deberíamos intentar satisfacer a la gran mayoría. Básicamente, porque si tu mezcla (que para ti es estupenda) no es del agrado de la mayoría, normalmente no durarás mucho en este trabajo…

La otra cuestión, totalmente cierta, es que para mezclar se aprende mezclando. Cada uno debe seguir su propio proceso de aprendizaje, escuchar, corregir, tomar decisiones y equivocarse. Por mucho que leamos cuestiones teóricas que nos puedan ayudar, tenemos que pasar horas y horas mezclando para ir mejorando nuestra técnica.

En este blog, compartimos algunos aspectos importantes a la hora de plantear una mezcla.

Cómo debería sonar?

Para empezar, siempre que podamos, deberíamos tener información sobre lo que vamos a sonorizar. Saber qué tipo de música hacen, y tener cierta cultura musical.

Para empezar, siempre que podamos, deberíamos tener información sobre lo que vamos a sonorizar. Saber qué tipo de música hacen, y tener cierta cultura musical.

De nada nos va a servir que un grupo nos diga que hace jazz si no hemos escuchado jazz. Así que, el primer paso es escuchar música de todo tipo, o por lo menos tener un concepto mental de cómo suenan diferentes estilos musicales, pudiera parecer una tontería, pero es algo fundamental.

Imagina hacer sonar un bombo con mucho click (reforzando la alta frecuencia) para un grupo de jazz, seguramente no funcionaría, por otro lado, ese bombo en una banda de metal podría encajar muy bien.

Si te encuentras en la posición en donde no conoces el genero de música que te pidieron mezclar, investiga su discografía y estilo, es una obligación prepararse lo mas que podamos, porque de lo contrario, ¿cómo vamos a poder proponer la mezcla?

Algo fundamental es escuchar la fuente que vamos a sonorizar. Acércate al escenario y escucha. El principio más importante de realizar una mezcla es capturar el sonido que ejecutan los músicos en el escenario y transmitirlo a los oyentes sin producir grandes cambios en la fuente sonora; A menos que nos lo pida el músico.

Planos y frecuencias.

De acuerdo, ya sabemos qué tipo de música hace la banda que sonorizamos, e incluso hemos escuchado los instrumentos desde el escenario. ¿Qué hacemos ahora?

Quizás puede ser un buen momento de plantearse los planos de la mezcla. Si tenemos, por ejemplo, una banda de rock con batería, bajo, guitarra y voz ¿en qué plano vamos a poner cada uno de esos elementos?

Es evidente que no podemos posicionar todo en el mismo plano sonoro. La mezcla trata, entre otras cosas, de eso: Algún elemento tiene que estar más alto y otros más bajos y en frecuencias pasa lo mismo: hay que repartir. Tenemos, en el mejor de los casos, de 20 Hz a 20Khz para distribuir nuestras señales. Si pretendo que todas compartan el mismo rango de frecuencias, se producirá nuestro querido fenómeno de enmascaramiento.

Debemos mezclar tomando diversas decisiones en nivel, así como contemplando la dinámica de las canciones, que normalmente los músicos son los encargados de matizar para generar desde la fuente estos cambios de nivel.

El siguiente paso es balancear, y ecualizar escuchando el conjunto.

La distribución de frecuencias realizando un mapa mental, donde hay que visualizar los distintos elementos sonoros, con esto se distribuyen dentro del espectro frecuencial. La experiencia te ira ayudando a delimitar dónde puede estar cada elemento con mayor rapidez y agilidad, por otro lado hay que revisar con detalle los elementos que pueden chocar con más facilidad entre sí por compartir rangos frecuenciales parecidos.

Por ejemplo, un bombo y un bajo. Sus frecuencias fundamentales comparten el rango de frecuencias bajas, por lo que se buscará conseguir que hagan un complemento entre ellos sin llegar a confundirse.

Para el balance, además de niveles, se utiliza también ecualización, dinámica y reverberación. La combinación de todos estos procesos es lo que nos permitirá crear mejores planos sonoros.

Para mayor detalle sobre los planos en la mezcla, uno de los libros que pueden consultar es

“The Art of Mixing”, de David Gibson, principalmente, por los gráficos en los que explica la distribución de los elementos sonoros en función del tipo de música.

LOS EFECTOS

Finalmente, comenzamos a preparar la mezcla con los procesadores de efectos que me permiten, en cierta manera, rematar ese proceso artístico, dándole el toque final.

Como punto de partida en cuestiones básicas, podemos colocar una reverb corta y una larga para crear planos, también se recomienda utilizar un efecto reverb plate y un delay para darle ese pequeño toque de magia, normalmente sutil y poco evidente, que sin embargo lleva la mezcla a un nivel superior.

Evidentemente, los efectos cambian en función del tipo de música y del espacio acústico donde nos encontremos o incluso en función de la canción, pues no todo sirve para todo. Antes de las pruebas de sonido, es recomendable probar los efectos con una voz o con una grabación que tengas en la computadora (virtual soundcheck), esto nos va a permitir elegir de forma más precisa el tipo de efecto que necesitamos de acuerdo del espacio donde nos encontremos, así podemos ajustar parámetros como el tiempo de caída o el predelay.

Conclusiones

Me gusta pensar que en la mayoría de las veces nuestro trabajo de mezcla en las sonorizaciones en vivo es tan sencillo (y a la vez, tan complicado) como capturar las señales del escenario de la forma más fiel a la original y transmitirlas al público con un poco (muy poco) de elaboración.

Los mejores resultados se obtienen primero pensando qué queremos hacer y después actuando y aplicando los procesos necesarios para llegar a nuestro objetivo. Puede parece obvio. Si logramos tener una imagen del sonido que queremos obtener en nuestra mente, siempre será mucho más fácil llegar a buen resultado.

Introduction to the mix.

Introduction to the mix.

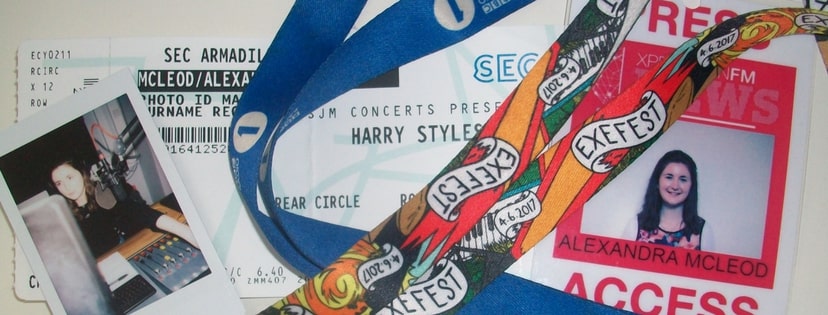

Why I Show Up & Reach Out: A Broadway Sound Mixer’s Story

Why I Show Up & Reach Out: A Broadway Sound Mixer’s Story 10 Women Loudly Pushing the Boundaries of Electronic Music

10 Women Loudly Pushing the Boundaries of Electronic Music