Coventry is a city in the middle of England, known for the legend of Lady Godiva, the WWII blitz, and for many years it was an industrial boomtown and subsequently a ‘concrete jungle.’ It is my hometown, a place that has given us a diverse selection of musical greats over the years spanning from Ray King, The Specials, and Hazel O’Connor to The Primitives, and The Enemy. Coventry was also the home of electronic composer Delia Derbyshire. Although I’ve had the pleasure of meeting, interviewing and performing in front of a number of this city’s musical giants, regrettably I never had the chance to meet Delia before her untimely passing in 2001.

Coventry is a city in the middle of England, known for the legend of Lady Godiva, the WWII blitz, and for many years it was an industrial boomtown and subsequently a ‘concrete jungle.’ It is my hometown, a place that has given us a diverse selection of musical greats over the years spanning from Ray King, The Specials, and Hazel O’Connor to The Primitives, and The Enemy. Coventry was also the home of electronic composer Delia Derbyshire. Although I’ve had the pleasure of meeting, interviewing and performing in front of a number of this city’s musical giants, regrettably I never had the chance to meet Delia before her untimely passing in 2001.

Delia was a musical pioneer, a unique lady with a sharp sense of humour, humility, and an unbridled passion for creating. The story of her contribution to the world has not taken up space as prominently as it should but is still quietly there nonetheless. I’d like to turn up the volume and tell you a little about her life and work, and why she is an iconic woman in music, who in my opinion possessed all of the ‘cool points’.

Early life

Fifty years before I would come to exist and first set foot in my childhood home, the place of Delia’s childhood home lay just five streets away. While I’m proud of where I come from, it is not a fancy area – it is one of honest, working-class roots. It’s still the kind of place today where earning the opportunity to study at Cambridge is an esteemed accomplishment only achieved by an exceptional minority. Delia Derbyshire was exceptional: she graduated from Cambridge University with a degree in music and mathematics at a time when it was the most prestigious location for studying mathematics, and when only 1 in 10 students were women.

Upon graduating, Delia approached Decca Records for work in 1959 only to be told they didn’t employ women in the recording studio. Heading to the BBC shortly after that in 1960, they were firm that they did not employ composers however Delia was hired as a studio assistant. She cheekily referred to this as ‘infiltrating the system to do music.’ Later that year, she joined the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, a role that was traditionally only short-term, the reasoning of which was rumoured to prevent the onset of madness. The Workshop provided sound design and music for a vast amount of TV and radio and was located in the mysterious room number 13, found at the end of a long corridor in Maida Vale studios.

The Radiophonic Workshop Years

Delia remained at the Radiophonic Workshop from 1960-73 and created her most iconic pieces in that time both freelance and for the BBC, the most well-known work being Derbyshire’s original Doctor Who arrangement. The theme was commissioned in 1963 and had an amicable story relayed in Spinal Tap-like fashion by Derbyshire’s contemporaries of the time: composer Ron Grainer had given Delia not a full musical score but a scribbled idea on a sheet of the manuscript with vague directions that she interpreted perfectly. His stunned reaction upon hearing the finished piece was to ask “Did I write that?!” to which Delia replied, “Most of it.” The original intention had been to hire and record a French band performing the piece on glass rims, however, the BBC budget was too tight, hence Delia was brought in.

It is worth noting that this period was before the synthesiser, and it may be useful to reflect on how incomprehensible it can be in our digitized lives to understand how Delia made electronic music in the mid-1960s. She worked heavily with a Wobbulator (portmanteau of wobble and oscillator), which was a sine-wave oscillator that could be frequency modulated and is also called a ‘sweep generator.’ Delia made the sounds she used both painstakingly and organically by inventing, manipulating and shifting samples that she often created from scratch, and this was all captured on reels of tape. For the Doctor Who theme, Delia used three layers and three tape machines at once for the final recording. Each note in the piece had to be individually cut and placed onto the tape reel. It is no wonder that all who knew her concurred that Delia was undoubtedly a perfectionist.

Whilst the Doctor Who theme has become her most famously known work; it came with its difficulties. The BBC had a longstanding policy of anonymity for the staff in the Radiophonic Workshop, and even when composer Ron Grainer wished to split the writing percentages and give Derbyshire credit, the corporation refused. Other creatives Delia had composed for made similarly fruitless acknowledgment requests. Years later, the BBC subsequently changed their rules on anonymity but declined to do it retrospectively. Delia got nothing for Doctor Who. Interestingly, the source of annoyance with the theme for Derbyshire was the number of times new producers at the BBC wanted to revamp it over the years. She was very vocal about her views and disapproved of all ‘tarted up’ versions other than Peter Howell’s.

The Swinging Sixties

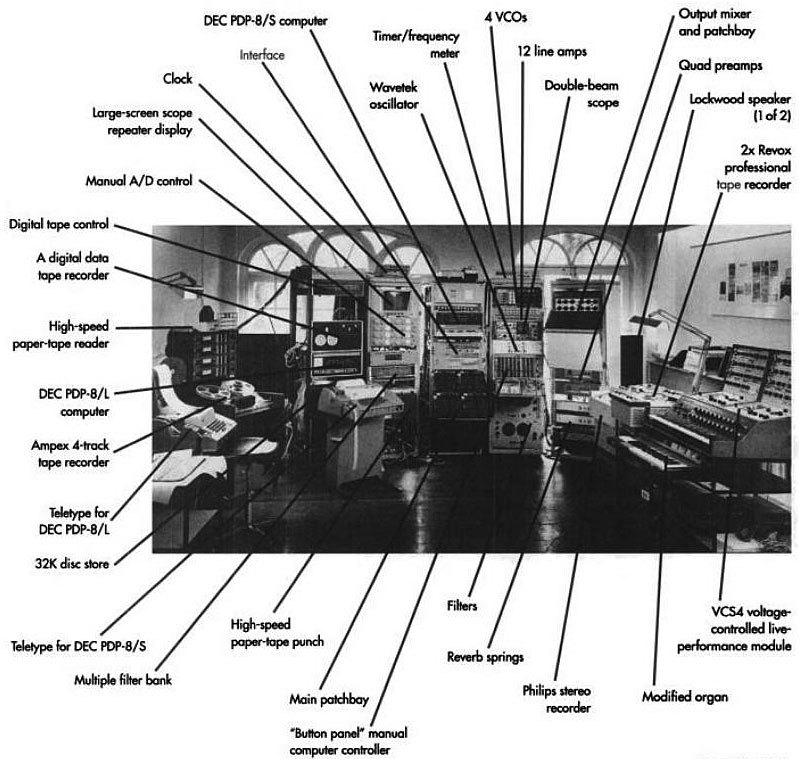

Aside from her BBC work, the 60s were a most fruitful time for Delia’s solo creations, and she also collaborated in several electronic band projects including ‘White Noise’ and ‘Unit Delta Plus.’ These works blurred the pre-existing lines of genre and broke many moulds in their experimental nature. Delia and her peers were highly influential and pivotal in shaping the music scene at this time: her ‘Unit Delta Plus’ bandmate Peter Zinovieff had a studio in Putney where Delia would often work which was known as EMS – Electronic Music Studios, and this was equipped with Zinovieff’s pioneering VCS3 synthesiser. Derbyshire believed in the generosity of knowledge and wanted to share her techniques and new discoveries with others. Some of the most quintessentially 1960s stories and sounds resulted from her remarkable contribution by the end of the decade.

Aside from her BBC work, the 60s were a most fruitful time for Delia’s solo creations, and she also collaborated in several electronic band projects including ‘White Noise’ and ‘Unit Delta Plus.’ These works blurred the pre-existing lines of genre and broke many moulds in their experimental nature. Delia and her peers were highly influential and pivotal in shaping the music scene at this time: her ‘Unit Delta Plus’ bandmate Peter Zinovieff had a studio in Putney where Delia would often work which was known as EMS – Electronic Music Studios, and this was equipped with Zinovieff’s pioneering VCS3 synthesiser. Derbyshire believed in the generosity of knowledge and wanted to share her techniques and new discoveries with others. Some of the most quintessentially 1960s stories and sounds resulted from her remarkable contribution by the end of the decade.

Delia was approached by Paul McCartney who requested she arrange a backing track for “Yesterday,” and he soon came in person to listen to some of her work at EMS. Shrouded in secrecy, Delia was then involved in the somewhat fabled electronic Beatles piece “Carnival of Light,” a legendary experimental track, which was played once and is now impossible to find. In a rare interview, she comically recalled “I did a film soundtrack for Yoko Ono. While she slept on my floor”, and the occasion when Brian Jones visited the Radiophonic Workshop and played with hand-tuned oscillators “as though he could play it as a musical instrument!” Delia was also responsible for bundling Pink Floyd into a taxi to EMS after the band visited her at the workshop to introduce them to Peter Zinovieff and his famous VCS3 – see “Dark Side of the Moon” for the outcome of that.

Creative process

Delia’s methods for composing are thought-provoking to me: she looked at music very mathematically and often assigned ideas to pitch and frequency with a meaning in mind, her starting point always being the Greek harmonic series. Being classically trained to a professional level pianist as a young woman meant that Delia’s music theory provided a solid knowledge of the rules in order to break them, her written notes highlighting this quirky combination with the use of graphic scores and colloquial musical and technical directions. She believed the way we perceive sound should have dominance over any theory or mathematical working. Delia herself cited childhood experiences as the earliest influences on her interest in electronic sounds, notably the ‘air raid’ and ‘all clear’ sirens she had become accustomed to hearing as a young girl during World War II that had piqued her interest in sound waves. I find it fascinating how such a combination of experiences can be a catalyst for such innovation and creation.

After the Workshop

Delia left the BBC in 1973 and is quoted as saying, “The world went out of tune with itself,” which is quite a heavy statement. She felt electronic music, and the common usage of synthesisers had changed music for the worse – it wasn’t organic enough as she always wanted to physically get inside equipment. It’s hard to know if her statement was borne from a reluctance to embrace the changing times and methods of making music, or perhaps how this had affected her role at the BBC, whom she openly blasted for being “ran by accountants” and “expecting her to compromise her integrity.”

Personally, I fear there may have been a sadness in Delia at this point, as she turned her back on working in music after leaving the BBC, taking on various non-musical jobs. She wrote lots privately, however never recorded, released or collaborated in the same way as she had in the 60s. Delia described herself as a utopian who believed freedom of creativity was more important than getting work, and I believe her. Perhaps the many years of blatant sexism, lack of credit, and working long through the night after everyone else had left were no longer sustainable if, in addition, her creative process was now being micromanaged.

Thankfully, by the mid-90s, Delia felt music was returning to it’s “pure” state and during the last years of her life Pete Kember a.k.a. Sonic Boom made contact with her by searching the Coventry phone book, eventually putting Delia in touch with the current generation of musicians she had inspired. He even persuaded her to collaborate, and she is credited as adviser/co-producer on two EAR albums, as well as co-writer with Kember on the track ‘Synchrondipity Machine’. Delia and Kember thought very highly of one another, and shortly before her death, she said “working with people like Sonic Boom on pure electronic music has re-invigorated me. Now without the constraints of doing ‘applied music,’ my mind can fly free and pick up where I left off.” It is bittersweet that the collaboration came so close to the time of her passing after all the silent years she’d endured.

Delia’s legacy

Her partner Clive discovered Delia’s back catalogue of tapes spanning her career after her death. The collection had been kept in the attic, stored neatly in cereal boxes, although time had not been kind to the labels that had once documented almost 300 reels of tape. A project to restore and archive the collection was undertaken by Mark Ayres, Dr. David Butler, and Brian Hodgson, and the complete collection now resides at The John Rylands Library at The University of Manchester and can be viewed by anyone upon appointment. The last work in the archive is a cue for an unmade film from 1980, donated by filmmaker Elizabeth Kosmian. Delia’s fascinating graphic scores and workings are also included as well as digitised sonic versions of her archived works.

Delia’s legacy lives on physically in The University of Manchester archive, and their associated organisation entitled “Delia Derbyshire Day” (DD Day) which offers events and activities promoting the art of British electronic music and history via the archive and works of Delia Derbyshire. For an interactive and family-friendly experience, Delia has a charming permanent spot of residence at The Coventry Music Museum. Online, there is wikidelia.net, delia-derbyshire.org, deliaderbyshireday.com, and of course, the many music download and streaming platforms on which Delia is still a presence.

Delia was a complex woman, one with oodles of personality and a sense of humour that shone through in the few rare interviews she did. Her friends and colleagues unanimously described her as an incredible planner, intelligent, analytical, fiery, and an eccentric genius. An enigma. She remembered, “Directors who came to see me work used to say ‘you must be an ardent feminist’ – I think I was a post-feminist before feminism was invented! I did rebel. I did a lot of things I was told not to do.”

Delia Derbyshire lived a fascinating life, and I wish I could have met her, to learn and understand more about her work and her mind. I’d be interested to uncover her thoughts on the 5% of women currently working in audio in 2019 and compare notes on the things that have changed so much, and the things that haven’t changed nearly enough. One thing’s for sure – if we ever discover the secrets to make time travel via Tardis possible, you’ll know where and when to find me.