2020 brought a variety of topics concerning gig workers in the US to light. From addressing unemployment for independent contractors to the House of Representatives introducing the P.R.O Act, Covid-19 is changing the conversation for the classification of gig workers. Florida introduced Uber Work, Uber’s new on-demand staffing business, in December 2019 to launch in its second city ever, Miami. Since March put a strain on the need for gig-based workers in the right-to-work state, I only recently had the pleasure of working alongside people utilizing this new app.

Some background information

One of the many struggles with event logistics during this time has been maintaining labor lists. Florida has fewer restrictions for venues drawing the attention of companies with events that don’t entirely rely on a live audience. Broadcast events like award shows have been navigating how to keep crews safe while still creating impressive rigs. Labor companies are eager to work and make promises to fill large calls, maybe biting off a little more than they can chew. Infrequent work has forced talented and knowledgeable hands to leave the industry temporarily to find steady day-work to make ends meet or leave entirely to transfer their skills to jobs less affected by the pandemic. You can’t always take off of work to take a few days of 8-hour calls.

It’s been interesting. When there’s one large event in my market at a time, I see the same friendly faces repeatedly regardless of which company is filling the call. You can almost work full-time under multiple companies. But it’s a little more complicated for those companies when there’s more than one event and as we’ve gotten further away from March 2020. Two different companies needing to fill 100+ calls can become very difficult very fast. Everyone is going to take the sweeter deal first.

What company is giving more days? How many hours a day? Who provides the better rate? Is there Covid testing? Parking? Hotel? Food?

What happens to the labor company that gets shorted by people being unavailable?

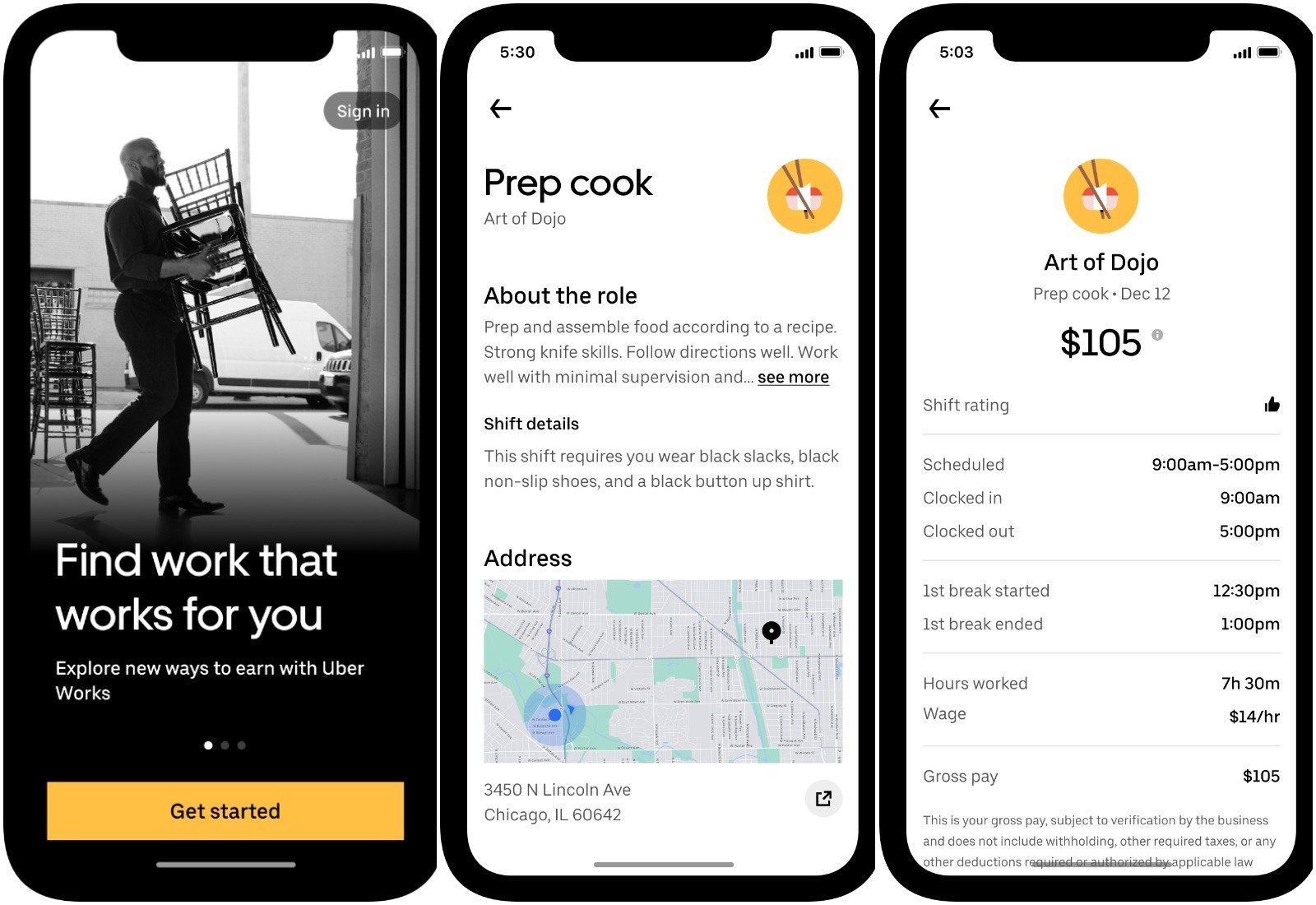

This is where one company that I was working for turned to Uber Works. A major selling point for this app is that people can take shifts for jobs that are entry-level and require very little previous skills. I can say with confidence, that is not the live entertainment industry. This job took place in a good-sized arena in Downtown Miami. I would never consider a fast-paced arena environment to be entry-level. We were already multiple days into this gig building the staging, raising video walls, flying line array, and lighting truss out. It’s an active work zone so I figured the crew of about 20 people would be coming in with tools and their own personal protective equipment. Most had no tools and just wore ankle-high boots (couldn’t say if they were safety toes). PPE was provided by the labor company but many of these workers would misplace their gear and it would be returned to supervisors by the end of the day.

Uber Works’ flagship city was Chicago. Miami has a very different logistical landscape when employing people. I’m not sure the company truly thought out some of the challenges different cities may have. English isn’t necessarily the default language for our work environment. Our crew is diverse and we tackled issues the company didn’t consider head-on with multiple translations for safety meetings, giving directions, and assisting anywhere we could. Uber Works didn’t consider possible accommodations they’d need to make to have this crew integrate smoothly. Language barriers become more apparent as things get more technical. Not every crew lead was bilingual. I found it challenging to try to explain signal flow to someone who has never seen XLR before. I was grasping at words to explain stage directions when they’ve never been on a stage before. This was taking on-the-job training to new levels.

It became very clear that while this technically solved the problem of not having enough hands, it came at a high price. How can I get frustrated with someone who was basically set up to fail?

The people from Uber Works who agreed to take on this difficult challenge were some of the sweetest, eager, willing to work people. They were pleasant to be around, they were patient and willing to learn, they tried to be aware of their surroundings in a possibly dangerous environment. I found that they shared some solidarity within their own group sharing a difficult experience and worked well as a team. I appreciated their enthusiasm but I personally can’t agree with ever having Uber Works on my job site ever again. Uber Works has a lot of kinks they need to fix and it’s not a solution for our industry.

For Uber Works to willingly send untrained people into an arena was reckless. There are inherent dangers to our field in dealing with heights, power, heavy machinery, and large loads. To add possible room for miscommunication exponentially increases that risk. These were people risking their lives to make ends meet during a pandemic where jobs are scarce and they were going in with their eyes closed.

The wonderful people who make up our industry are not easily replaced by someone deemed “unskilled” by a large corporation. We have a wealth of knowledge that is often built up from years of experience and dedication to our craft. I’m hoping in the future labor companies will be more willing to split bids with other companies in order to properly fill calls for clients. I’m also hoping companies like Uber Works don’t continue to devalue our labor. You can’t penny and dime our skillsets or take a commission on an hourly rate. A low-balling bid war during this time wouldn’t just set back rates; it would push so many more away from an industry that they love.

The gig was chaotic, but I think that says more about the companies who agreed to these terms than the working hands.