This is a blog I should have written years ago. But better late than never, right? So 20(!) blogs in we’re finally getting to some theatre basics: who’s who in the world of theatre audio. I’ve touched on some of the jobs in other blogs, but today we’re going to hit all of them. After all, you can’t be what you don’t know, so let’s make sure you know what your options are!

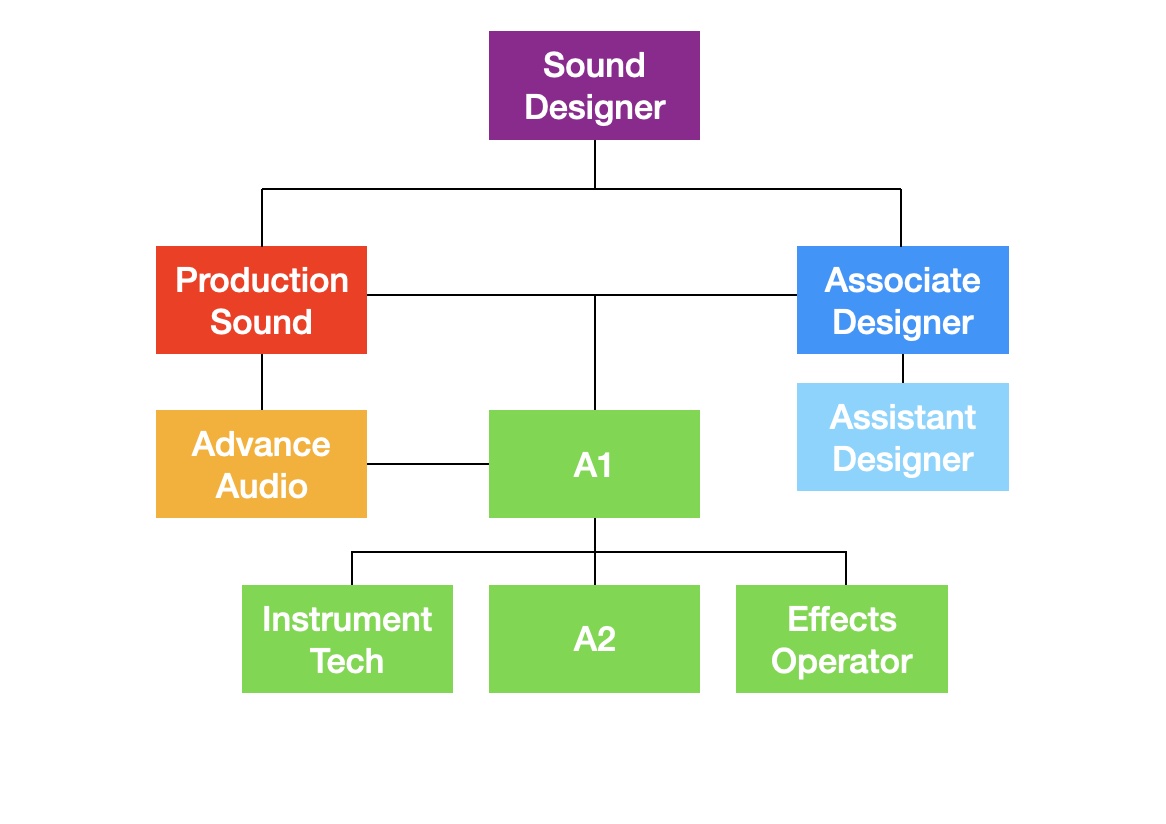

The sound team is usually comprised of

The Sound Designer

The designer is in charge of the big picture: creating a design concept, communicating with directors and designers, and delegating to their team. What their exact duties are in relation to their team will differ from team to team depending on the skill sets of each person. Some designers are composers (those tend to do a lot of plays since the music for a musical is done by someone else) or are more focused on the design aspect of creating soundscapes or effects. Others are more involved with the technical side of things: the gear, the system, etc. Either way, designers will specify the gear they want to use (console, speakers, mics, processing, etc) and collaborate with the director and other designers on the artistic scope and special needs of the show.

The strengths of a designer help determine who they look for while creating their team. Most designers end up working with associates or assistants that have complementary skills. If they’re more creative, they might work with someone who can provide insight into what gear can accomplish what they want to do. If they’re more technical, they might want someone good with coaching a mixer or creating sound effects.

The Associate Designer

The associate acts as the designer when the designer isn’t around. They have worked with the designer before (usually on multiple projects), know how to set things up to their liking, and the designer trusts them to take care of projects on their own. They might have started as an assistant or a mixer with that same designer and they work closely with the Production Audio to get the sound system put together and installed.

Sometimes a designer has multiple associates. When we teched the Les Miserables tour, the designer, Mick Potter, had three tours teching at the same time: Les Miserables, School of Rock, and Love Never Dies. Each tour had an associate to get the sound system loaded in and tech the show. Mick split his time between the three shows, trusting his associates to get everything ready and roughed in, scheduling his time so he could be at each show for their mission-critical moments like Quiet Time (when the sound system gets tuned) and Cast on Stage (the first day the cast is onstage in mics for tech). The associates could go to him with questions when he wasn’t there, and he didn’t have to actually be in three places at once, even though it very much seemed like he was for that month. As you can see, with multiple projects going at the same time, having an associate that they can trust is absolutely essential for a designer.

The Assistant Designer

The assistant’s job is very similar to the associate. However, while an associate can act in the designer’s stead, the assistant typically has to get permission before making changes. The division of labor depends a lot on the dynamic and skill sets of the team, especially if there’s both an associate and an assistant on the show.

The Production Audio

This is a job I talked about in detail in another blog when I was in Production for a tour. Production is in charge of taking the system specified by the Designer and turning it into a reality, accounting for every connection, cable, piece of gear, nut and bolt, and loading it (or installing it in Broadway’s case) into the theatre.

Advance Audio

The advance position is found on larger tours that need extra people to load in, but not during the show run. An advance crew usually has at least an Advance Carpenter, Electrician, and Audio, but may also have a person for rigging, automation, or other specialties. They get to a venue before the show-to-show crew (the ones that run the show) and start loading in. When I was on the most recent Phantom of the Opera tour, our advance crew started in the theatre on Monday while we were loading out and traveling to that city and we’d join them and continue loading in Tuesday and Wednesday, then they’d leave on Thursday. On tours like Aladdin, the advance load in lasted several days before the show-to-show crew arrived, which isn’t surprising when you consider they had a magic carpet to set up!

The Mixer (A1)

This is what most of my blogs focus on, especially the first one, but in brief, the mixer’s job is to run the show, blending vocal and instrumental mics to execute the Designer’s concept for how the show should sound. They are the head of the sound department which involves contacting the shop if there is a problem with gear, making sure the department (deck and local audio as well) have everything and all the information they need, and on tour talking to future venues and developing a plan for load in.

The Deck Audio (A2)

The A2 is responsible for running the deck track (mic swaps, handoffs, etc), maintaining microphones, and troubleshooting mid-show, and they will mix the show on a regular basis to act as a cover for the A1. (In NYC, sometimes there is a “non-mixing” A2, which means there is another person, not in the building on a day-to-day basis, who’s trained on the mix.)

Other jobs

Depending on the needs of the show, other positions may come up. Sometimes there are so many sound effects that the mixer can’t run them and accurately mix the show at the same time, so an Operator position is created for someone who is designated to run effects for the show. Or there might be lots of live instruments played onstage so an Instrument Tech is added to the show and may fall under the sound department.

That may not seem like a lot of people at a glance, but it can make for a lot of moving parts, and knowing who to communicate with for a given problem is key. So, who do you talk to when you have a question? During prep in the shop or tech in the theatre, it’s easy to get anyone’s attention because you’re all in the same room. Once the show is up and running and Design and Production have left the building, who’s your go-to now?

On tour my main point of contact is the associate; they’re usually accessible to double-check on things or so you can pick their brain. They end up being a natural choice because you end up spending the majority of your time in tech with them anyway.

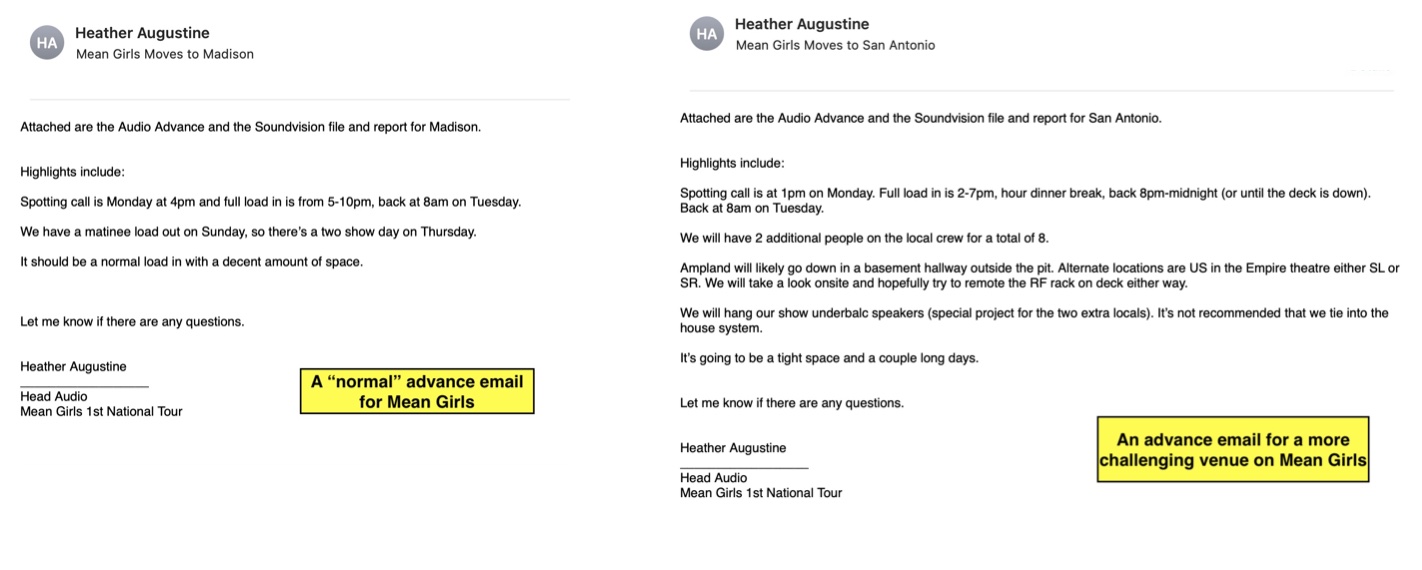

For the first few moves on tour, I’d have the Associate check the preliminary speaker prediction I did, then review any adjustments I made once we were in the theatre. Once they felt comfortable that I knew what the Designer was looking for and could make informed choices on my own, they would check in less and less, unless I asked for input on something specific. They also got copied on the advance email I sent to my A2 before we loaded into a new city which had the plan for the venue, any special thing we might have to take care of, or if it would be a normal day.

They are also the contact for any comments or concerns that pop up in addition to the questions. Some examples are if there are audience complaints and you need some help figuring out which adjustment to make, or if the actors or management have requested something that will change the design of the show. One common request I’ve run into is actors asking for vocals to be put in the onstage speakers. This is usually something that is decided either in or well before tech and isn’t in the mixer’s purview to change. That gets sent to the associate either as a “can we change this?” or “please respond so someone higher than me on the food chain has reiterated that we can’t, and we can end this conversation.”

If the Associate needs to involve the Designer, they will. Other than that, the Designer might stop by on occasion, maybe every 6 months to a year, to check in on the show (in which case I’ll also include them on my advance emails for that load-in). Other than that, they may not have much to do with the day-to-day of the show.

If I have system or gear-specific questions, I’ll usually ask the production audio, since they’re the ones that built the system and spend a lot of their time around the gear. On tour, they might not have much to do with the show once it’s up and running, but in NYC you might contact both the associate and the production audio with questions. They might also be involved in finding people to sub on the mix or the deck track and figuring out training schedules.

One thing to mention is pay. Ideally, associates and production are paid what’s called “weekly” which is a weekly fee, past whatever salary or flat fee they got for production and tech. This is paying for their continued time and assistance to keep the show running and answer questions. However this isn’t always the case, so that’s something to keep in mind. If my associate is being paid weekly, but production isn’t, I might send my question to the associate first to see if they can answer it before asking production to spend time on something they aren’t getting paid for. Oftentimes, they are happy to help regardless because they want you to be successful and their name is still on the show, but some people may be protective of their time if they aren’t being directly compensated for it.

While we’re talking about communication, let’s touch on other departments that we regularly need to talk to

If I need to address something that involves the actors, but isn’t related to music, I’ll talk to the PSM (Production Stage Manager). They are the glue between all departments, managing the company’s schedules, communication, and on top of that running a show. Notes usually go through Stage Management so they know what’s going on and what to watch out for. From sound, our notes are usually simple: it could be that an actor’s mic placement was out of place, the A2 has adjusted it, but then the actor put on incorrectly the next show. Or someone has changed a line or blocking that affects how or when I take a cue. This communication goes both ways: they’ll let me know if someone’s sick and might need a little help in their big moments, or if there’s trouble hearing something musically onstage and can I see if there’s anything I can do at the board to help?

Anything music-related will go to the MD (Music Director, who usually conducts the show). They’re your link to the musicians as well as the actors. If an instrument consistently sticks out where it’s not supposed to, or you need an actor to give you a little more in a quiet bit of a song, you can go to the MD with notes and they will be able to pass it along or work with the actor on the note if it’s a reoccurring technical problem in their singing.

Someone in the pit, besides the MD, will be designated as a Keyboard Tech. They are there to help if there’s a problem with the software controlling the patches for the keyboards. For sound, as long as we’re patched in correctly, we’ve technically done our job. We’ll never be asked to tune the timpani or restring a violin. However, keyboards are an exception where the instrument and the gear are so intertwined that we might be asked to help the Tech troubleshoot, even if it isn’t directly our responsibility. On the other hand, when we’re checking out the system during the preshow and test the keyboards, we would call the Music Tech to help if there’s a problem that a re-boot or some simple troubleshooting doesn’t fix.

For other issues, usually departmental or personnel, you go to the Head Carpenter or the Steward. The Head Carpenter is the head of the crew, submits payroll, sends out schedules, coordinates and oversees local and show labor on load in and out on a tour, etc. They are the ones you go to with logistical questions that involve special situations or the local crew, setting up work calls, or helping if there’s an issue among crew members. The Steward is there to answer questions about the contract and help if there ever seems to be an overstep or inconsistency.

Returning back to the sound team to wrap it up: interdepartmental communication is some of the most important. The A1 is the head of the department, so gets official communications like performance reports and is likely to be the first point of contact for notes. If the information is necessary or even just helpful, the A2 should know about it. The A2, on the other hand, gets most of the informal communication. They’re backstage, so they’re the ones within earshot if someone needs to pass along a quick note if Wardrobe has heard that one of the actors will be calling out for the evening show, or if there was a last-minute change in the schedule and the official email hasn’t gone out yet. Communication is always a two-way street, and an open policy keeps both parties well-informed and valued.

Sound is one of the few departments that touches every single other during the show run. Between com/video, mics, and music, we cover it all. Which means there can be a lot going on at any given point. Hopefully, these guidelines will help if you’re ever unsure who to talk to!