This month’s blog is kind of a pseudo-philosophical question. Does it matter what we call things? Of course, it does; it’s not the name itself but what it connotes for us aesthetically, culturally, and any other …ally you can think of. So, I may end up proving myself wrong on this, but at least I should have a better understanding…

On a personal level: is my music experimental? I’ve proudly declared that it is and have been sometimes “snooty” about other terms. So, I’m going in for a bit of Megahertz cleansing. See! I just wrote something, and I don’t even know what it means; so gawd knows what you, my dear reader, will make of it. However, I digress …

I can’t remember when or why I started referring to myself as an experimental composer. I think the why was because it sounded cool and besides, any time I mentioned electronic music to friends, they immediately envisaged me in a basement club surrounded by flashing lights and entranced dancers (is that me being snooty?). Also, I had seen it as a genre, for example, it can be searched for on the Bandcamp website, where they tell us that, …

The artists represented here aren’t interested in tradition. Whether it’s clattering avant-garde music, deafening drone, or wild improvisation, artists who define their music as “experimental” are all interested in the same thing: pushing the boundaries of what we consider “music,” and finding fascinating new song shapes and structures.

Apart from the rather ‘unkind’ adjectives, there is a sense in which artists will feel that that is what they are doing when they compose. Following a few of these tags on the Bandcamp label in a purely random fashion, I went from experimental to musique concrète, where I found an Example from Eliane Radigue, ‘Feedback Works 1969 – 1970’. She does indeed come from the musique concrète era, having worked with Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry. I then linked to drone music, where again I found a composition by Eliane Radigue, ‘Occam XXV,’ which was written for organ in 2018. Is this experimental music? According to Bandcamp and the tags assigned, it is, but I believe it less so than her 1969 Feedback works, I’ll look at this later in relation to what John Cage considered to be experimental music. So, pressing on with randomly linked tags, it seemed that noise and, in particular, harsh noise might be representative of a kind of experimental music. In this category, ‘Human Butcher Shop’ also tagged as metal, was a kind of slash guitar with distorted feedback; the kind of thing Jimi Hendrix was doing in the 70s. So, to my mind, not really ‘pushing the boundaries…’, which makes me think that these kinds of criteria are not really helpful in trying to find a true home for experimental music; always assuming that the quest is a valid one.

I think, therefore, that the Bandcamp definition of experimental music is not really helpful. Does it matter what labels we attach to music? I would suggest that it does to the artists, in the sense that the label helps define us as artists in the eyes of our audiences. I assume that as a search tag it might be useful for the consumer, even if there is still a lot of trawling to be done. Before I leave Bandcamp, and as an example of how trawling and labels can lead to serendipitous moments, I decided to give ‘Dysfunctional Voiding’ by Piss Enema a quick listen. The cover was ugly by any standards, but then I imagine that this was the intention of the artist wishing to occupy a certain genre as suggested by their tags: experimental, death industrial, harsh noise, power electronics, etc. However, the music was not dissimilar to other styles of musique concrète, even if less appealing, to my ears anyway. So, as I had supposed, this adventure proved to be less than fruitful when one remembers that online tags create links and therefore visibility. So, if you put your music on a music site, you would probably put as many related tags as possible to reach your intended audience.

NB: I have included links to Bandcamp tracks, and my understanding is that you can listen once to sample a song, but not repeatedly.

I mentioned John Cage earlier, so let’s see what he has to say about experimental music, a term he was using as early as 1955. But first, some other attempts at definition and some of experimental music’s characteristics. According to Wikipedia, Experimental Music is not to be confused with Avant-garde music and this is qualified in this definition from the website ‘MasterClass’:

Though the terms “experimental” and “avant-garde” are sometimes used interchangeably, some music scholars and composers consider avant-garde music, which aims to innovate, as the furthest expression of an established musical form. Experimentalism is entirely separate from any musical form and focuses on discovery and playfulness without an underlying intention.

In other words: Experimental compositional practice is defined broadly by exploratory sensibilities radically opposed to, and questioning of, institutionalized compositional, performing, and aesthetic conventions in music.

So, if in my own work, I take a recorded sample and try to push it to create new sounds, or become a part of something greater, am I being experimental? Do I have exploratory sensibilities? Yes, I think I do. Am I questioning the accepted conventions of music practice as they are? Again, in my work, I think I am. It seems to me that it all depends on the kind of music we are making. If we are to use environmental sounds, as the Futurists in Milan had already done in the early part of the 1900s, then it does perforce suggest deprecating musical convention. It is interesting to note that Pierre Boulez a composer of aleatoric music could be quite conventional when conducting. His recordings of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and Debussy’s Trois Nocturnes are faithful to the scores. So even the arch-modernist knew when to be radically opposed to musical convention and when not to be.

As we shall see, John Cage’s definition of Experimental music includes elements of indeterminacy and chance, either in its composition or its performance in such a way that the outcomes of the music are unknown. Indeterminate, or aleatoric music used ‘chance’ as a key component. Cage’s “Music of Changes” of 1951 uses the I Ching Chinese text to influence the sound and length of each performance. Chance, but at the moment of listening and recording, is present in Pauline Oliveros’s “Cave Water” of 1990 where the dripping of water is not under the slightest control of the composer.

https://paulineoliveros1.bandcamp.com/track/cave-water

I earlier referred to the two pieces by Eliane Radigue, who had worked in the 50s with one of the prime movers of Experimentalism in Europe, Pierre Schaeffer; Cage would occupy a similar role in the US. In Occam XXV, Radigue wrote the piece for organ to be performed by an organist with no room for improvisation, as far as I can tell. The Feedback Works 1969 – 1970 were composed in her home studio, which she used while bringing up her three children. The equipment at her disposal: three tape recorders, a mixing board, an amplifier, two loudspeakers, and a microphone were used to create the feedback works. With her children asleep, she often worked through the night in her basement home studio, holding a microphone, shifting it here and there by small increments thus playing with the feedback. Since so much depended on the microphone, speakers, the limits of the magnetic tape, and the acoustics of the room, there is that element that the outcomes of the music are unknown. This chance element of how the music will be when the compositional process is finished certainly gives this piece its experimental status. By the way, Eliane’s last electronic composition was in 1998, L’Île re-sonante. She continues to compose, but for live instruments. In fact, at the time of writing, she has a concert at the INA GRM Salle de Concerts in Paris this coming Wednesday, the 26th of January alongside another of my favorite experimental composers, Félicia Atkinson. Eliane’s first track, Stress Osaka is the shortest at 11:35 and it’s pretty cool – a lot to listen to.

https://elianeradigue.bandcamp.com/album/feedback-works-1969-1970

This track, the hidden, from Felicia’s newest recording, especially the second half, frames her elegantly in a long line of French composers of “musique experimentale” later to be changed by the same Pierre Schaeffer to “recherche musicale”

https://shelterpress.bandcamp.com/track/the-hidden

Are any of the gifted women experimental composers, experimental? Can a ‘live-work which might contain elements of indeterminacy, for example, improvisation and/or ‘chance’, be considered experimental? Would a studio recording of the same piece still be considered experimental? That depends… if it is/was considered experimental at its inception then the answer appears to be yes, given Cage’s assertion that the experimentalism can be contained in composition or performance.

Two artists who are well into indeterminacy at the composition phase are the London-based artist Klein and Claire Rousay from San Antonio, Texas. When performing live, they may also experiment in performance: both artists have live performances coming up, by the way: Klein in Bristol, 26th January, and London 30th January, Claire Rousay in Knoxville (TN), 25th March

https://klein1997.bandcamp.com/track/needed-and-saved-2

https://clairerousay.bandcamp.com/track/stoned-gesture

https://clairerousay.bandcamp.com/track/a-kind-of-promise

Claire Rousay is particularly interesting and this album, a softer focus represents her at her most melodic, almost pop. From Bandcamp: claire rousay is based in San Antonio, Texas. Her music zeroes in on personal emotions and the minutiae of everyday life — voicemails, haptics, environmental recordings, stopwatches, whispers, and conversations — exploding their significance. The link below is to a short interview with Claire Roussay. Me, I’m struck by her authenticity:

https://daily.bandcamp.com/features/claire-rousay-softer-focus-interview?utm_source=footer

Klein’s work has been described as “grainy pop collages,” using heavily manipulated audio samples, drones, and sonic artifacts induced by time-stretching and pitch shifting. She assembles her tracks in sound editing program Audacity

I’m beginning to think, well actually a while ago now, that the word experimental is not so important, especially since there are other definitions we could use for this kind of music. But what kind of music is it? And what kind of music is my music? So, the question is now, am I an experimental composer? If you read my January blog, you will know that I’ve been picking up on music from forty years ago. Yes, even then it had elements of indeterminacy, but the style then was to process sound sources until one arrived at the kind of sound we had been seeking. On the other hand, I remember using a random number generator on the EMS 100 synth to haphazardly scramble the input of my sound source, giving me a kind of bubbly granulated texture. However, the finished piece had been crafted to a loose narrative structure and existed as a composition of ‘fixed media’. The only variations that could be made in performances, were the diffusion of the sounds around a sound space through an array of loudspeakers. So, what is my music? My course at the conservatoire is titled musica elettroacustica II. Fair enough since it uses recorded acoustic sounds and electronics to modify and add to the composition. In performance, the music is called Acousmatic music on fixed media. In other words, it is a musical object whose performance does not necessarily require the composer’s presence; this is often discussed as to what is our role at a concert if we just sit in front of a laptop? Obviously, other possibilities exist: the electronics can be combined with live performers, the electronics can be controlled and distributed in an improvisatory way, through the use of prepared loops and touchpads. For example, Ableton Live has a feature for stage performances:

Note chance

Set the probability that a note or drum hit will occur and let Live generate surprising variations to your patterns that change over time.

This is all fine and dandy but this is Frà’s blog, and she still hasn’t answered her own question: is her music experimental? I come from a mixed musical background: Italian tenor arias in infancy while listening to my father practice; the rock and roll years as a teenager; as I moved into my twenties it was Jazz, but not any old Jazz. It was the free-form stuff from late Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, Giuseppe Logan Who??? Anyway, from them to Soft machine in the 70s and then, behind the curve as always, I was introduced to Stravinsky, Debussy, Messaien, and off I went to Uni to study music and Fine art. So, with this mixed evolutionary musical background and my ADHD (which has been a bit of a bother [we English gals are very good at euphemism -it’s more like manic] is why this blog is particularly discursive – I am drawing to a close, I promise).

Anyway, where were we? Ah, yes; so, I have a kind of quasi-classical background which means experimentation and extemporization have been a part of my musical language: I performed Terry Riley’s “In C” at Uni alongside other fairly “free” pieces, but I think I’ve been too stuck in the musique concrete style up until now. Realizing that maybe I’m not as experimental as I thought I was. My next piece, “Aston Expressway” (which I am writing for my son – you’ll get the story when the piece is finished) will make more use of unexpected samples in the making, though I have a narrative for the concept. Indeed, at the moment, since I’m still vague about it, If I don’t compose it, it will remain uber experimental.

As I’ve been writing this, I’ve been listening to EST’s live Hamburg recording of Tuesday Wonderland which is much longer than the studio recording, has live electronics and free improvisation, so also fitting the criteria for experimental. However, since it already has a tag of Jazz, it probably doesn’t need to claim its experimental credentials, even if what is happening on stage and is being recorded is in all likelihood experimental.

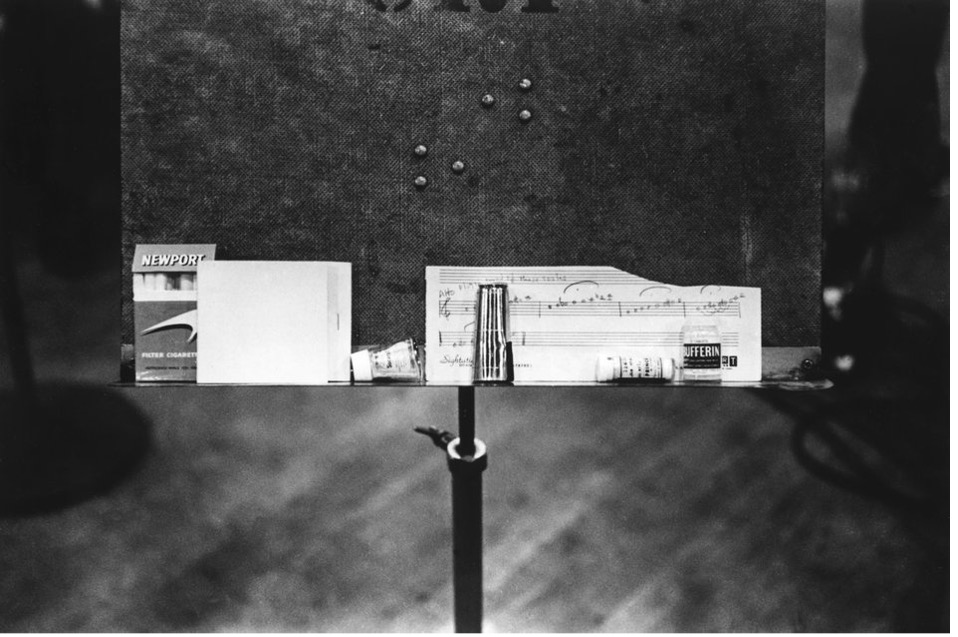

Just as a side note, Kind of Blue, arguably one of the most well-known jazz records of all time was mostly improvised. The photograph below is Cannonball Adderley’s music for Flamenco Sketches, a piece that lasts nine and a half minutes. Since they were improvising within recognizable musical forms, it is hard to call it experimental, even if the second take is different from the first. But who cares? It’s still a great piece of music and both takes are beautiful as works of art in their own right? Coltrane’s entry is just out of this world as is Cannonball Adderley’s and Bill Evans of course, the rest of the band are delicately there… Sorry but I haven’t listened to this in a while and I’m frozen to the spot, in a good way …

So, if I’ve been over-picky about a commonly used genre of music (I am Virgo after all), it’s not to deny anyone agency in their chosen field, but simply a reflection on what some of us and me, in particular, are trying to do with the music we create. I come back again to this word authenticity, which is beginning to become a bit of a mantra for me; not all music can be authentic in its existence, it may just be a jingle selling a product (actually, if I could write a few, I might make some money) but that which excites me is the art that connects one person to another. It’s not always easy to recognize but I do sense it in much of the work of the younger generation of experimental composers – there, I used the word. If I can connect through my art, I’ll be happy to be called simply a musician.

Pierre Boulez, the French composer, and conductor, in his response to critics of the ‘New Music’, who he referred to as Ostriches, said that “There is no such thing as experimental music … but there is a very real distinction between sterility and invention”.

So, there you have it, it either doesn’t exist or it’s everything that’s inventive.

Invent, connect and be authentic.

Frà sends her love from Torino to SoundGirls everywhere.

Frà sends her love from Torino to SoundGirls everywhere.