The skills involved in producing and engineering music are different to the ones required to write and play it, but that does not say there is no overlap. Even the simplest recording job requires you to be able to capture the feel of the music, and the vision of the musicians, on record. All of the technical know-how in the world won’t matter if you have a tin-ear for the music, and so it’s helpful to make sure your knowledge of producing and engineering is backed up by an understanding of musical theory.

One of the most common examples of musical theory that is crucial to the creation of music is the circle of fifths. You may have read, or heard, someone say of a song: ‘It uses the classic I-IV-V-I progression.’ Unless you are already familiar with intermediate musical theory, this may well have baffled you; after all, you know that the scale runs from ‘A’ to ‘G’, and you know that between the notes are ‘sharps’ and ‘flats’, but that’s it. The answer to this is that ‘I-IV-V-I’ is a progression, not from one specific note or chord to another, but a pattern that repeats in terms of spacing, whatever the ‘root’ note or chord of the sequence. This progression can be explained by the concept of the circle of fifths, and in a recording situation, this could be vital knowledge. The reason is that music is written to evoke or elicit certain feelings and emotions, and there are methods for doing so, compositionally speaking; an engineer’s job is to ensure that the recording matches the vision, and an understanding of how the music works makes that job easier.

I-IV-V-I

Music is basically maths- that’s the first thing to remember. Notes sound pleasant, or consonant, together because of the mathematical ratios between them. A ‘fifth’ is the term for a specific interval between notes. To stay with the example of ‘I-IV-V-I’- mainly because it is the most common progression in popular western music, with literally thousands of songs based up in it- imagine that the starting chord of your song is a C-major; that is ‘I,’ your ‘root’ chord. ‘IV,’ your next chord, is F-major and ‘V’ is G-major. If however, the key of ‘C’ is not right for your voice, be it either too low or too high for you to sing comfortably, the ‘I-IV-V-I’ pattern can be easily transposed. If you want to sing in the key of E-major (I), then the next chord will be A-major (IV), followed by B-major (V). The progression will sound the same, only in a higher or lower key; this is because the intervals between the notes are the same. The same goes for other common progressions, such as I-V-VI-IV; if it is denoted by Roman numerals, then it is all about the intervals and can be transposed into any key.

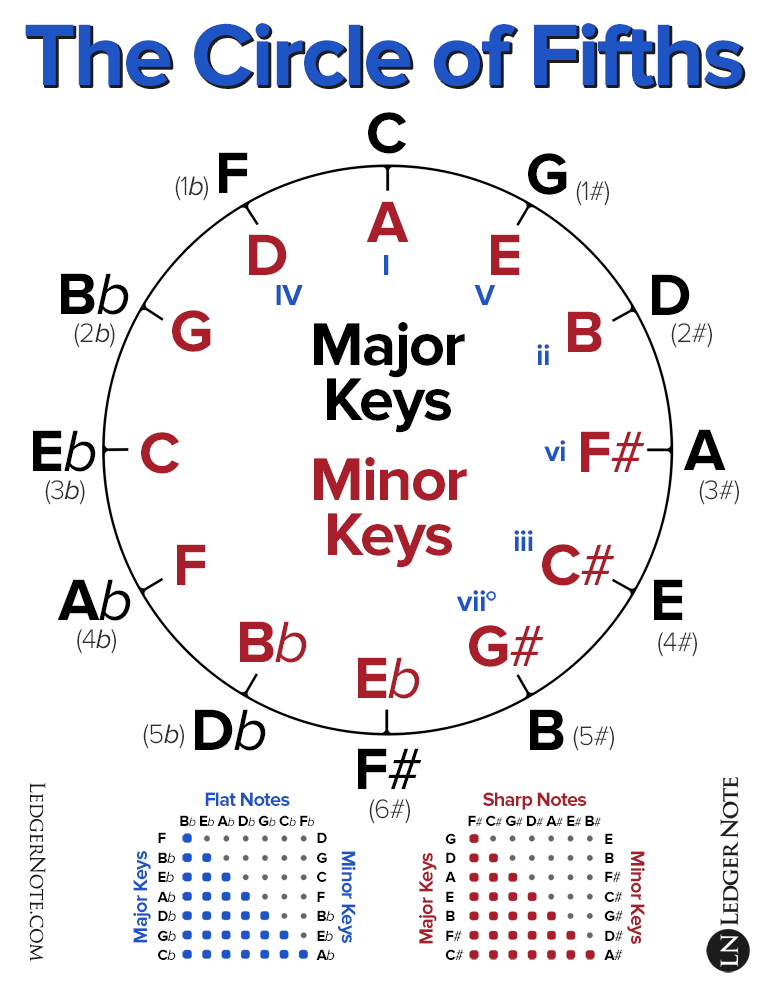

The circle of fifths is so called because the nature of the musical scale, running from A to G, means that you can start on one note and run through a sequence of ‘perfect fifths’ which will take you through each note and back to the beginning, in a circular motion, without experiencing any dissonance. It is also because this relationship can place, visually, on a circle; this diagram makes it easy to locate both the relative minor chords as well as the ‘IV’ and ‘V’ of any root note or chord. A simple trick to remember is that, on the circle of fifths diagram, the ‘IV’ of any root note is one step anti-clockwise, and the ‘V’ is one step clockwise.

The circle of fifths is so called because the nature of the musical scale, running from A to G, means that you can start on one note and run through a sequence of ‘perfect fifths’ which will take you through each note and back to the beginning, in a circular motion, without experiencing any dissonance. It is also because this relationship can place, visually, on a circle; this diagram makes it easy to locate both the relative minor chords as well as the ‘IV’ and ‘V’ of any root note or chord. A simple trick to remember is that, on the circle of fifths diagram, the ‘IV’ of any root note is one step anti-clockwise, and the ‘V’ is one step clockwise.

There’s a great deal more theory behind this, and it becomes increasingly complex and esoteric, but if you want to understand how songs have been put together,- an important part of the recording process- then a basic understanding of the circle of fifths will be beneficial. The diagram, in particular, will show you consonant choices about chord progression, whilst also showing you the relative minor chord, which is always a favorite option for a middle-8 or B-section. As you better understand how the music works, your abilities to successfully capture its spirit will also increase.

By Sally Perkins