Part 1: The system and the show

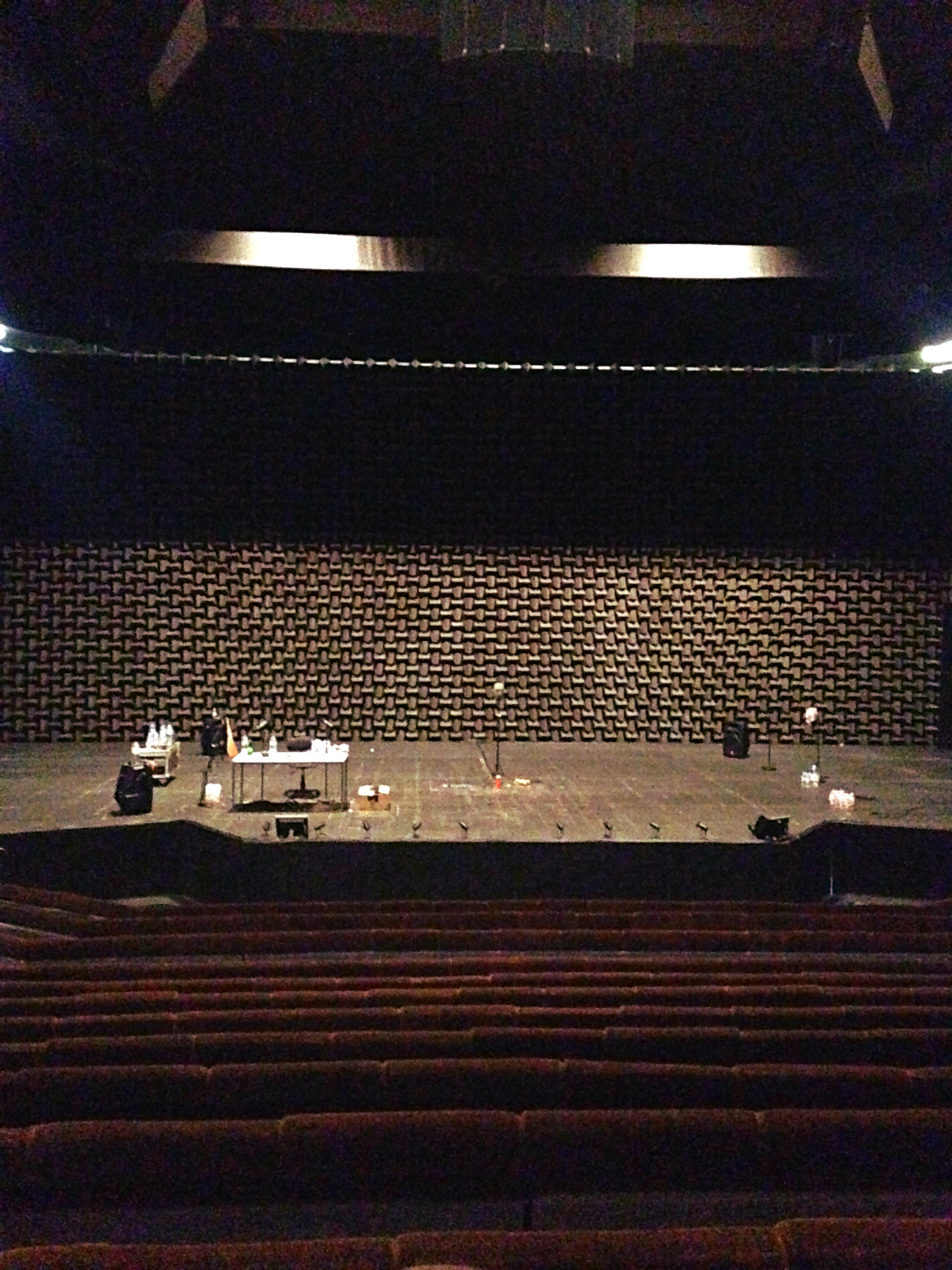

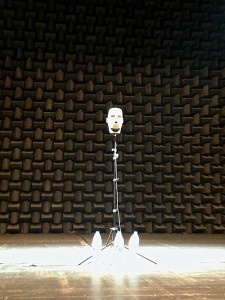

A man is whispering into my left ear. I turn my head to face him but the guy on my left smiles and shakes his head. It’s not him: my first experience of live binaural sound has confused my ears. On stage, sound designer Pete Malkin is talking into the left ear microphone of a binaural head and consequently, into the left ear of my headphones and the headphones of other members of the Association of Sound Designers. I’m at the Barbican Theatre in London to learn about the concepts and execution behind the sound design for Complicite’s The Encounter.

The Encounter is a solo show directed and performed by Simon McBurney, produced by international innovative theatre company Complicite and sound designed by Gareth Fry with Pete Malkin. The show is based on a book about the experience of National Geographic photographer Loren McIntyre, who had an encounter with a remote Amazonian tribe in 1969 that changed his life. Innovative sound technology and Simon’s mesmerizing performance create the world of the Amazonian rainforest and all the characters that inhabit the story. The audience wears headphones for the entire two-hour experience.

Let’s start with Simon’s voice, both as himself and as multiple characters, some of which are him as well. Single words and sometimes full sentences are looped. You hear live, and pre-recorded binaural recordings as different characters in your ears, inhabiting a particular space and so real you feel they surely must be there, just behind your right shoulder maybe, or walking behind you from right to left. But it’s just Simon on stage, talking to the voice of his past self, recorded last year, or perhaps in the last minute.

Back in the backstage tour, Helen Skiera, one of the two sound operators along with Ella Wahlström explains her responsibilities, using bespoke hardware to switch between two handheld mics, Simon’s headset mic and the binaural head, with Lexicons to process and pitch his voice up and down for different characters. She also uses Qlab for control messages and Ableton for live looping, reacting organically to Simon’s performance to loop phrases, individual words, and sounds from any mic. A soft foot pedal that Simon operates on stage connects to Ableton via Qlab and Launchpad, which allows Helen to control the output if necessary.

The Foley sounds that Simon creates on stage are also captured, affected, and looped, as he tips water bottles for the sloshing of the river, tramples on cellulose tape for jungle undergrowth, and plays audio clips through an iPod and small domestic hi-fi speaker into various microphones.

The pre-recorded sound effects and music are operated by Ella, running Qlab and Ableton simultaneously. Her Qlab system has over 300 cues, including conventional cues with audio tracks for music, sound effects, and pre-corded voice overs plus cues that trigger loops and reset faders in Ableton. The fader resetting is crucial: like Helen, Ella reacts to Simon’s performance as she operates, manually riding the levels through each scene.

As you watch and listen to the play, the sounds duck, dip and dive around you, and really, everything seems to come from anywhere within the virtual space between and around your ears. Such is the beauty of binaural sound. Planes seem actually to fly above you, voices whisper in your ear, Amazonian tribespeople dance next to you, mosquitos buzz around your head.

As I listen to the sound team describing the sound system, it becomes apparent that its complexity was the result of an overriding need for flexibility. As Gareth puts it, they wanted to allow for many more ways of storytelling as Simon and the team explore different ways of communicating the story to the audience. The Encounter is a devised show and, in true Complicite style, no-show is the same, with Simon improvising as he sees fit.

An example of this appears early on in the show. Simon seems to create rules, using specific mics for specific characters. Minutes later he breaks these and the voice that we expected to hear coming from one static mic now comes from his headset mic, or the binaural head. The system has been designed to contribute to the creative process. As Helen puts it “the performer can be near anything [any mic] and turn into anything” – a character with a deeper voice, for example, or an animal – and the sound operators will be able to react to that and incorporate it into the story.

The show itself is an evocative, emotional, astonishing ride. Gareth and his team have achieved the extraordinary feat of creating a soundscape so dense and layered that you feel like you’re at the heart of the story and at the same time, each sound is so clear that you never lose a moment.

Read The Stage’s article for a look at how the binaural sounds were captured for The Encounter, including Gareth’s trip up the Amazon.

Next month – Part 2: an interview with Helen & Ella on the challenges and rewards of operating sound for The Encounter.