Sound design for a baroque opera – Part 1

“Does an opera need sound design?” a lighting designer colleague queried when I told them about my latest job as the sound designer for a re-discovered baroque opera staged in a 19th-century music hall.

It’s a fair question. How do the elements of sound design, specifically amplification and pre-recorded soundscapes, fit with a traditionally amplification-free musical production?

Pre-recorded sound effects have been used in opera for decades, especially in large dramatic works, as recorded sound FX replaced practical effects like people shaking thunder sheets for Wagner and thumping church bells backstage for Puccini. Modern opera has also embraced contemporary sound design techniques alongside other high-tech elements. Here is an interesting review of Sunken Garden by the English National Opera (ENO) and describes how the technical aspects of the production are an integral part of the story.

Amplification has also started to creep in as opera moves outside of traditional opera houses and into larger modern spaces designed with amplification in mind.

However, the opera that I faced was neither grand nor modern. My job was to create a sound design for the first-ever performance of a 17th-century drama burlesco opera, performed by an early music ensemble playing period instruments, set in a run-down modern mental asylum and staged in a 19th-century music hall.

It was a unique challenge.

Rehearsals

A lost manuscript and a dystopian vision

Back in 2003, the musicologist Naomi Matsumoto found a forgotten 17th-century manuscript score with the title “l’Ospedale” (The Hospital). The libretto, set in a mental asylum/hospital, was written by 17th-century Italian poet Antonio Abadi; the composer was unknown. The musicologist suggested the work to baroque collective Solomon’s Knot in the UK in 2008, and they developed the opera through multiple workshops over several years.

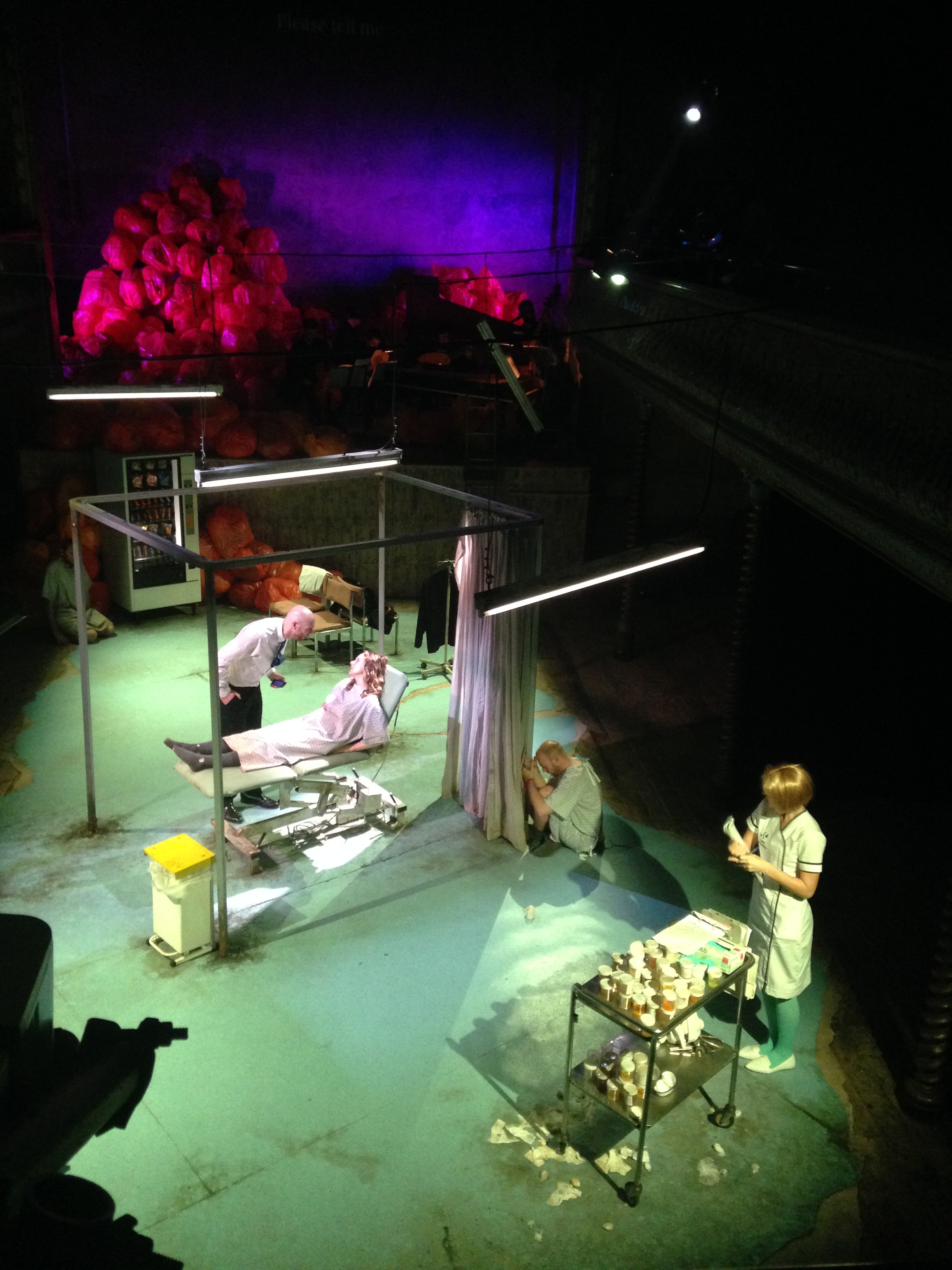

By the time I became involved with the production in October last year, the opera had been set in a run-down 21st century dystopian mental institution with an intentionally immersive feel. The stage area was thrust (open on three sides) and in the stalls (ground floor), with the ensemble on the raised physical stage of the venue.

The director and musical director (MD) wanted the sound design to reinforce the contemporary setting and bridge the gap between the baroque score and the modern design. As well as a pre-show soundscape, I needed to produce a pre-recorded prologue and epilogue, in English, of a modern-day Minister of Health presenting his theory on health reforms (to replace Abati’s original speeches by the “God of Health”. We also decided to underscore some of the key moments in the opera, including two unaccompanied madrigals, a “mad” scene, and what the Stage Manager charmingly termed the “urine ballet” scene, where one of the characters submits a urine sample after submitting to his fate of staying in the hospital.

For musicals, the paramount concern for the sound team is that every line (sung or spoken) is distinct. In opera, the music in its entirety is the central concern, and everything else in the production comes a distant second. So it made sense for me to start my job with where the music would be heard (the space), and how (acoustic or otherwise). After seeing a few runs of the entire opera in rehearsals, my next stop was a site visit and chat with the musical director.

The historic music hall

Wilton’s Music Hall in East London is the world’s oldest surviving music hall, built in a time when live performance was a primary form of entertainment and amplification was something you did if you shouted loudly. As soon as I walked into the main space and performed a few initial clap tests to assess the RT60, I knew the venue would do most of the work for me regarding being able to hear the music. As The Arts Desk review put it, the acoustic is: “studio-clean for solo singing, while ensemble passages ring with church-like resonance. Those 19th-century builders really knew what they were about.“

When no mics are better than one

There was only one harpsichord used as accompaniment in rehearsals, and I wouldn’t hear the full ensemble until the dress rehearsals. I had to, therefore, call on my knowledge of (and happily, degree in) Baroque & Renaissance music, and the advice of the MD, to assess whether the musicians would need amplification. The ensemble consisted of two harpsichords, viola de gamba (a baroque version of a cello), violone (baroque double bass), baroque guitar, and a lute.

Rehearsals

Given the musicians would be elevated and behind the singers, I initially thought I would need to close-mic the quieter string instruments (lute and guitar) to make them heard above the singers and the harpsichords. When budget constraints prevented this, I trusted that the timbre of the instruments would make them easily audible in the mix of sound, and thankfully, I was proved right. In fact, mic’ing the lute and guitar would have added nothing to the performance. Proving that sometimes the easiest solution is the best one!

With the venue assessed and the ensemble requirements scoped, my next task was to introduce the pre-recorded elements of the sound design and decide on speaker placement.

Next month: Part 2 – when less is more: the challenges of combining a modern medicine-inspired soundscape with baroque music