July 2019 has seen a “guilty” verdict passed on the latest high profile copyright case in music: Katy Perry’s entire musical team were ordered to pay damages to Christian rapper Flame for copying his 2008 track “Joyful Noise” in her US No one hit “Dark Horse.” The most interesting thing to me, in this case, is that the musical elements in question are not part of a complex or distinctive melody, a musical progression or harmonic sequence, but a 4 bar beat that includes an eight-note synthesiser ostinato loop. The notes in question and the nature of them under any kind of musical scrutiny highlight a few potentially significant implications for the future of music.

There is no “magic number” of notes or hard and fast, black and white rule of what copyright infringement is in a purely general sense, so each case is always a unique comparison to be argued. When a copyright case is brought to court, the comparing of lead sheets (consisting of melody, chord progression, and lyrics) is the general method of analysing whether a song has been copied for legal purposes. Musicologists are often called in to explain in layman’s terms how these line up and compare, and it is common for both sides to bring instruments into court to practically demonstrate points to the jury in context.

Analysing the lead sheets, in this case, is interesting because of the section this case is looking at – the beat. The drumbeat in both tracks is traditional where the main kicks and snares fall, although Flame’s kick has more variations and additions on extra off-beats than Perry, and he also shifts from claps to snares in the voicing. As such, Joyful Noise is the more complex beat musically.

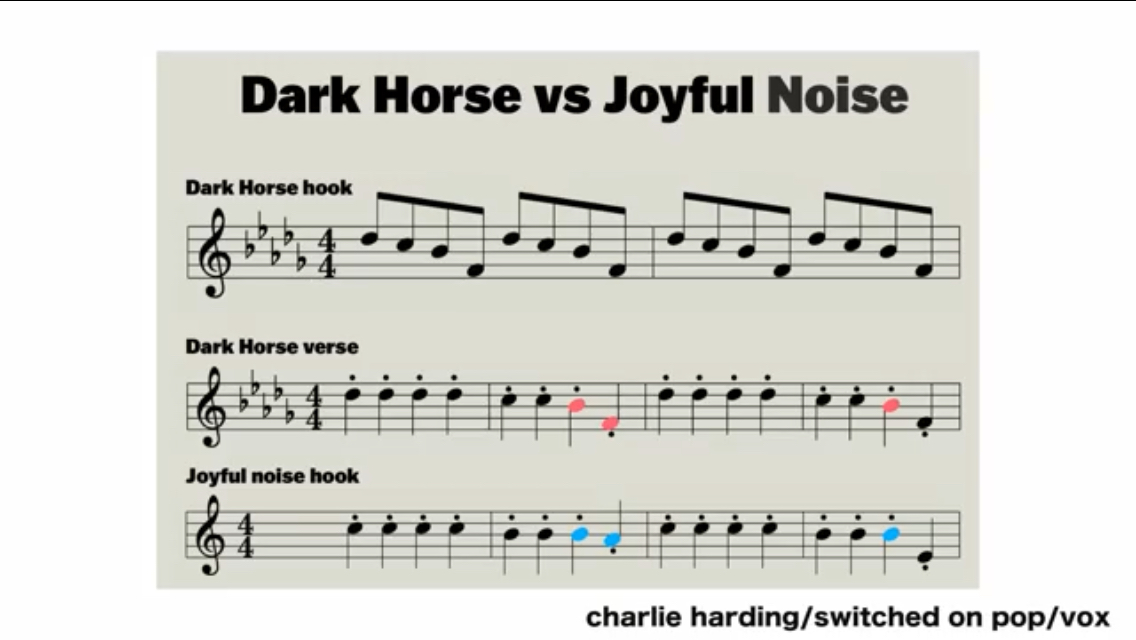

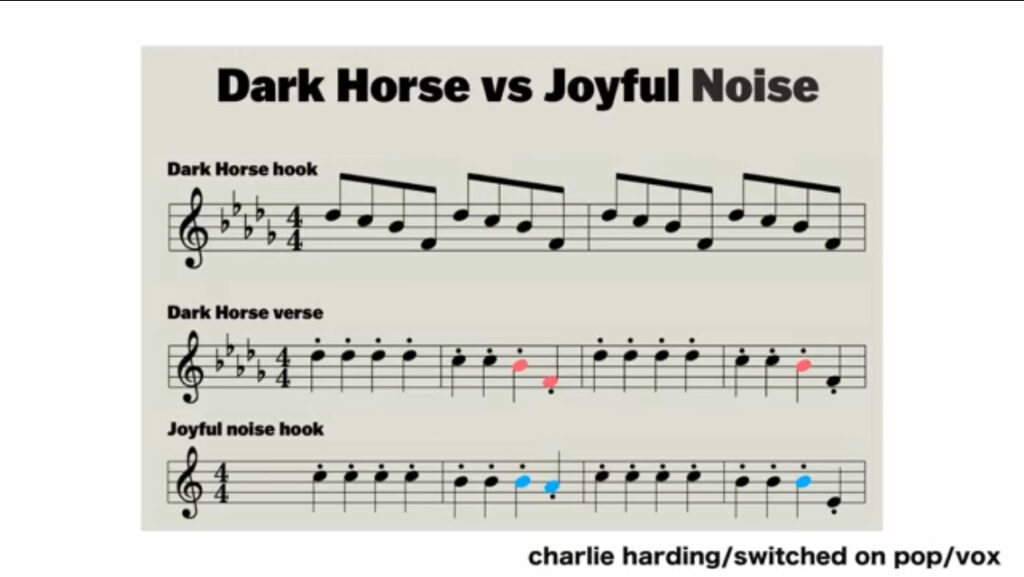

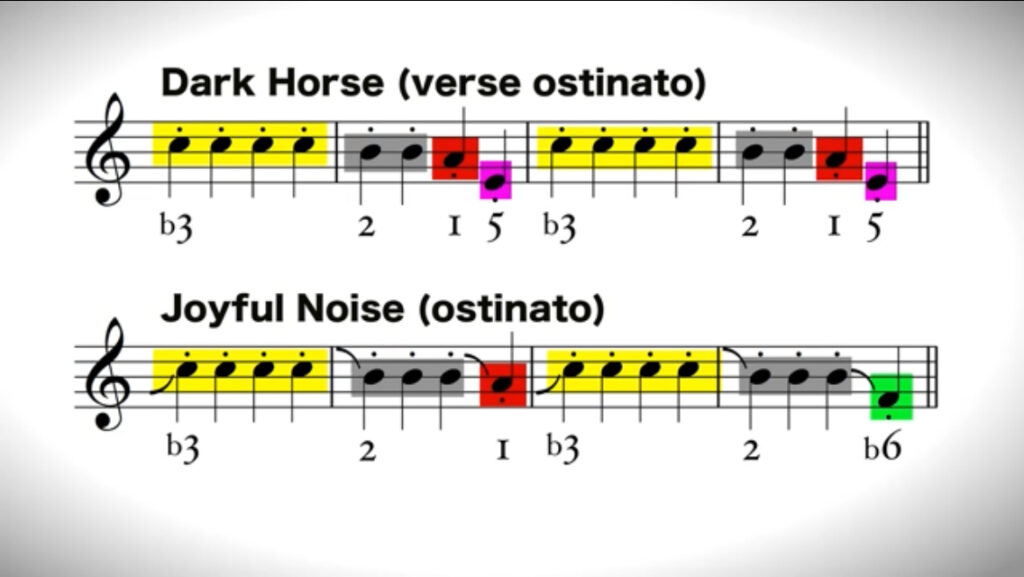

Looking at the synthesiser ostinato melody is more realistic in where the similarities lie. The instrumentation is vastly different – Joyful Noise uses a sawtooth wave sound with a heavy glide or portamento at the start of each pitch change, while Dark Horse uses an airy artificial vocal sound, giving them completely distinct tones and timbres. Charlie Harding’s transcription of the sheet music shows the real song keys used, however, if we mentally transpose either track one semitone to look at them both in the same key, we can see obvious duplication. The first four notes are the same, and the pattern of intervals then falls one semitone for the notes 6 and 7. The 8th note lines up again only on the second repetition of the eight-note phrase. This is a typical descending minor scale pattern as shown in Adam Neely’s transcription, which he has transposed for clarity.

While the similarities in the synth parts are apparent, the reality of them musically must be emphasised – what Perry’s team and most musicians would argue in this case is that they are excerpts of a minor scale. Rhythmically it is difficult to factor in an argument as every note falls on the beat. While nobody can deny that the two synth parts are similar, it needs to be understood that the reason they are similar is the simplicity and genericity of the line, found in nursery rhymes, esteemed classical works, folk songs, and instructional book 1 of almost every pitched instrument the world over. The literary equivalent would be something such as “I would like a glass of water” – a phrase so necessary and well-used that it could not possibly be assigned as being an original creation of the 21st century.

Perry’s lawyer Christine Lepera argued the prosecution was “trying to own basic building blocks of music, the alphabet of music that should be available to everyone.” If we are not careful, we run the risk of copyrighting musical necessities, the letters of the musical alphabet Lepera references, most likely not understood by the non-musicians who ruled in this case, which raises the question of whether a musically illiterate jury should be involved in the decision making process?

Of course, there’s likely an element of PR dumbing down for media purposes with the umbrella phrasing of “the beat” being found at fault in this case, yet my analytical side is deeply dissatisfied with it. Looking at the argument from Flame’s expert; however, it makes a little more sense. The prosecution’s musicologist Todd Decker stated the ostinatos had “five or six points of similarity including pitch, rhythm, texture, pattern of repetition, melodic shape and timbre. The descending melodies of both ostinatos are unique. I have not seen another piece that descends in the way these two do.” He also said, “the synthesised sounds create a pingy, artificial sound in the beat.” If the entire “beat” (and all of the rhythms, variations, and scales this includes as previously mentioned) is now copyrighted by Flame, what does this mean for music, other than us all running home to spice up our drum tracks?

Another worrying part of this ruling is the fact that all six songwriters and the four corporations involved in the release were found liable, making this an extreme verdict, no matter how removed from “the beat” or synth line the individual or company may have been.

It feels like there have been significant copyright cases every few years in recent times, and while intentional plagiarism is, of course, a wrong to be avoided, it’s worth remembering that we are all the product of what has come before us, whether unconsciously, through education, or out of love or rebellion. Under real musical analysis, it feels quite wrong in principle to be marred with the label of stealing someone’s “vibe” (see the much-discussed Pharrell & Robin Thicke case) or for obeying the long-standing rules and traditions of Western music, as is my view on the Perry case. Hopefully, creativity will continue to thrive among all of us sharing this somewhat limited 12 note system, and terms such as influence, tradition, and vibe will evolve to their more logical meanings rather than being worrying words within the industry.