Wherever you are in your career, I believe there’s always something new you can learn. It’s a bit of a buzz when you encounter a new skill, then master it for the first time.

At the start of this year, near the top of my list of skills-to-learn was mixing large-scale (West End, Broadway, or touring) musicals. The majority of my experience as a theatrical sound designer and operator so far has been soundscape design and mixing for plays, live variety and dance productions. Although I have experience mixing for small musicals and bands and music ensembles, my experience with large-scale musicals has been limited to backstage tours and being an enthusiastic member of the audience.

It was a gap that I felt I needed to fill. After all, if I want to work at a high level in theatrical sound design, it makes sense that I know as much as I can about all aspects of theatre sound.

For those who haven’t worked in large-scale theatre in the UK before, here’s a brief overview of the sound team structure. It is similar for touring productions and I imagine probably for large-scale theatre in the US as well. The sound designer is at the top and handles both the live sound and the prerecorded sound – systems, mics, soundscapes, backing tracks and liaison with the creative team. Under the sound designer, is the production engineer who fulfils a similar role to a system tech: what goes where and how it all fits together. The Sound No.1 reports to the sound designer, is primarily responsible for mixing the show and manages the No.2 and No.3. The Sound No. 2 is based backstage and is in charge of radio mics and will also learn how to mix the show so they can deputise for the Sound No. 1. Larger shows will have a Sound No. 3 (and some have a No. 4) who will deal with radio mics as well and will dep the No. 2 when necessary.

The established route to becoming a No. 1 (the person who mixes the show) is to rise through the ranks. Starting as a No. 3, moving up to a No. 2 on the same show (or a different show), and after enough experience, moving up to work as a No. 1. Many drama schools and universities in the UK, which offer technical theatre courses, provide students the chance to work as No. 3 or No. 4 as part of practical placements. It is common for technical theatre graduates who specialise in sound to go into No. 3 positions when they graduate, and then work up the hierarchy from there.

This is great if you trained in London or at a drama school with links to London theatres. For those of us who come to London from countries without a large theatre scene, or who are based in smaller theatres outside of London, the opportunities to work as a No. 2 or No. 3 on a large show may be few or non-existent. It was certainly that way for me. I’m also at a stage in my career and my life where I can’t afford the time it takes to work up from a No. 3 position. So how could I learn how to mix musicals?

Enter the Orbital Sound course Mixing for Musicals, held over a two-day period at Orbital Sound in south London. I found out about the course via the Association for Sound Designers and it seemed exactly what I was looking for. A chance to get my fingers on faders and practically learn about what it feels like to mix potentially 80+ channels in one show.

Enter the Orbital Sound course Mixing for Musicals, held over a two-day period at Orbital Sound in south London. I found out about the course via the Association for Sound Designers and it seemed exactly what I was looking for. A chance to get my fingers on faders and practically learn about what it feels like to mix potentially 80+ channels in one show.

Arriving on the first day, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Orbital Sound is an established and respected hire company who provides sound systems and sound design services for high-level productions around the world. I wasn’t worried about the quality of training, but I was slightly concerned whether I had potentially signed myself up for two days of debating the pros and cons of the config of Digico vs. Yamaha desks. There are only so many acronyms I can take before my brain hurts.

Thankfully, I had nothing to fear. One of the best aspects of the course was that it catered to most levels by establishing the level of knowledge of the group. Then structuring the amount of time spent on theory, questions and practical experience accordingly. There was plenty of time spent on establishing the basics of modern musical sound systems, speaker placement, matrixes and VCAs. There was also time made for those in our group who did want to talk about Digico T automation vs Yamaha recall safe. Best of all, over half of the course was hands-on experience of programming a desk and learning how to mix line by line.

The biggest learning curve for me was VCAs (also known as Control Groups or DCAs, depending on what make of desk you use) and automation. Modern musicals are all about mixing line by line – when someone isn’t speaking or singing, their mic is completely off. Modern musicals typically use over 40 radio mics for the cast (including two for each principal performer) and 30+ band mics. Then add in soundscape and backing tracks, sound effects, and the monitor mixes. It becomes impossible to mute and unmute each track at the right moment, let alone ride the faders at channel level.

This is where automation comes in, with the programming of the desk becoming vital to the effective mixing of the show. The DCAs act as remote controls for the channel faders. Instead of the operator having to call up a specific channel in the layers of the digital desk each time they need to alter the level, that channel is remotely operated by one of the 8-12 DCA faders. For any given scene in the show (with the desk “scenes” corresponding to changes in what the audience needs to hear, rather than scenes in the script), the operator needs to have control of the mics that will be live in that scene routed to the DCAs. They then can pull each fader up and down as each performer, or group of performers speaks or sings. When the scene changes, the DCAs will control a different set of channels, so while DCA 1, 2 & 3 controlled Chorus 1, Narrator and Steve in (desk) Scene 1, they might control Chorus 2, Susan and Steve in Scene 2.

On top of this automation is another level of automation involving EQs, reverb sends, other effects, whatever is specific to the show. And once you’ve programmed everything into the desk, you get to see whether it all works during the tech or in our case, using the multitrack recording of the live show.

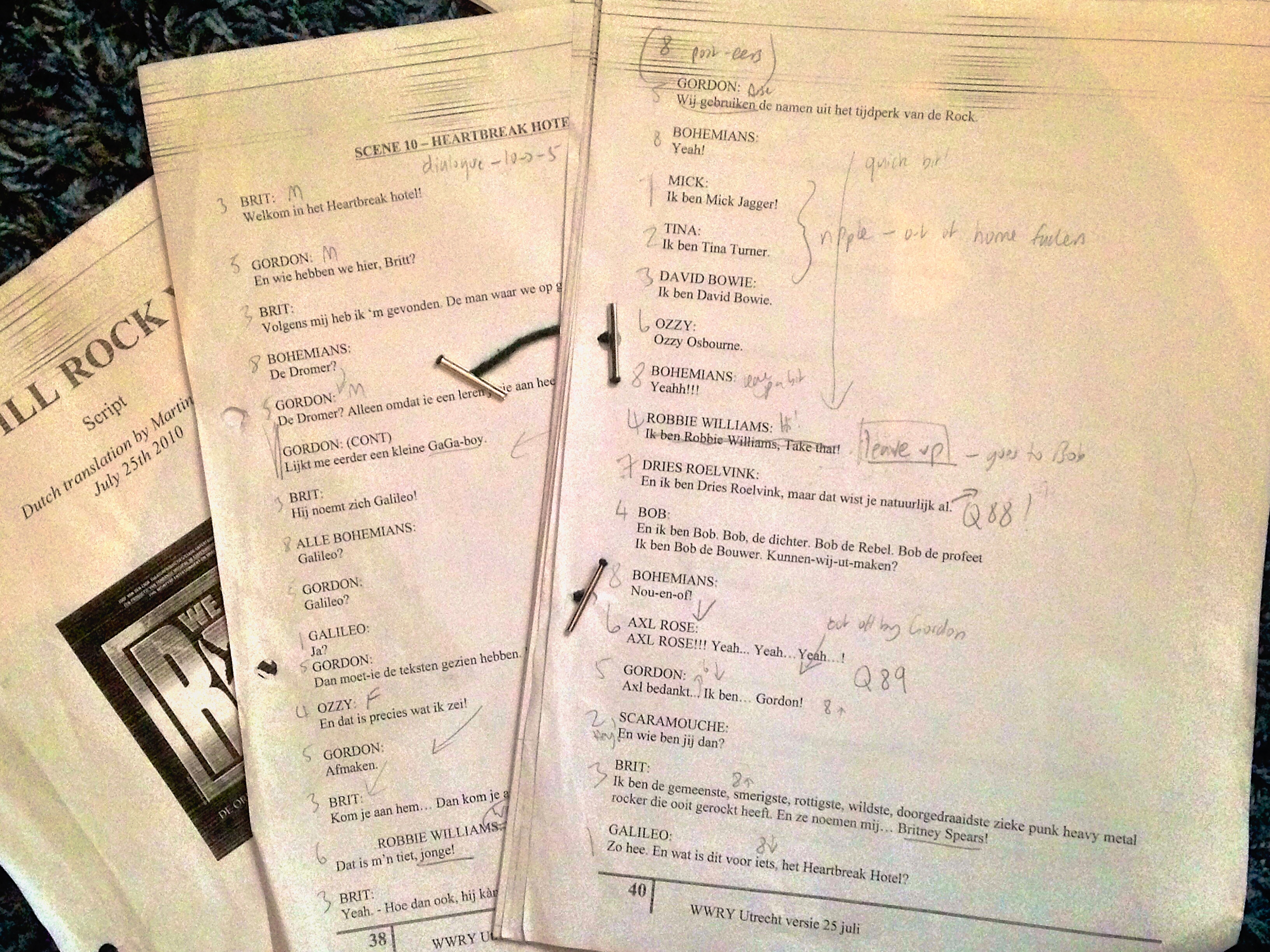

The practice of recording live musicals onto multitrack is the reason courses like the Orbital course can teach people how to mix musicals. Many large productions now budget for a DAW system as standard, both for commercial show recordings and as a teaching resource for Sound No. 2’s or touring sound ops learning how to mix a show. A No. 2 can load up any scene on the desk, find that scene on the multitrack recording, hit play on the multitrack and mix that scene as if it was live. They do not have to inconvenience any performers or musicians. On day two of the course, we had the chance to mix scenes from the Dutch touring production of We Will Rock You, the most recent West End production of Evita and a semi-pro production of Rent, on three different desks, all without leaving the Orbital premises.

The course also covered radio mics, A/B systems, score reading and speaker zones in theatres (e.g. stalls left & right, circle left & right, centre, fills and delays). How to use the desk matrix to route different sources to zones at different times, which is a totally different way of looking at speaker placement compared to a modern rock gig.

Overall it was a challenging, enlightening and fun two days. I left with a much better understanding of what goes into designing and operating a large-scale musical, and the confidence to look at expanding my musical design and operating experience. Although I’ll probably start with panto, rather than the West End.

Note for non-British readers an explanation of pantomime theatre

Yes, it’s a valid and thriving form of musical theatre in the UK. Don’t worry, I don’t quite get it either.