Within the past couple of months, life has started to pick up, and start dates for live events seem more and more like true beginnings and not the “fingers crossed!” of last year. But after a year and a half, the landscape looks a little different. People who had been on the road for decades suddenly had extra time at home and realized that they didn’t want to head back. Others who were on the cusp of starting their careers can finally see opportunities pop up and are ready to hop on the road.

If you’ve never been on tour before, here are some tips and tricks to get you started. (For clarity’s sake, I’ve only toured in the theatre world. I would assume that some of this translates to concerts, but I’m not saying that it absolutely does.)

Most of the tour advice boils down to: don’t be an idiot and don’t be an asshole

If nothing else, remember that. So much of our life is dealing with different personalities, across departments, the touring company at large, and your local crew. If you and the people around you are pleasant to work with, your day gets immediately better. So, keep in mind:

- You’re going to be working with your road crew every day for the next year, maybe more. Treat each other with respect and professionalism. This also applies to locals. You will have crews with varying levels of experience and knowledge, but never treat people like they’re incompetent (unless they unequivocally prove themselves to be so and are unpleasant on top of that). You know your show, they know their venue. I’ll usually tell the local audio head “I’ll tell you what I need to happen, you tell me how it needs to gets done.”

- Help when and where you can. Give a hand carrying a cable or notice that another department’s behind and see if you can work on a project that keeps you out of their way.

- Learn people’s names. Every new venue you’ll have a new set of local crew members (usually 4-6) helping you load in or out. When you meet them, ask for their names. If you have trouble remembering names, make a note of it on your phone or write it down. It’s a simple gesture of respect and much nicer than having to say “hey…uh, green shirt, can you help me?”

- If you forget someone’s name, ask.

- Your first priority is to learn how to do your job, after that you can worry about making friends. You’ll naturally develop friendships while you’re working and interacting with your crew, but no one wants to hang out with the person who’s constantly making mistakes, slowing down load-ins, or getting in everyone’s way because they don’t know what they’re doing.

- Whenever you have a disagreement, be the first to extend an olive branch. I’ve had a handful of times when I’ve butted heads with people, usually over practices a designer has dictated, which I can’t change or the circumstance doesn’t require an exception. After the show, I made a point to initiate a conversation and say I knew our interaction wasn’t pleasant, but I was still there to help, even if I couldn’t always give them exactly what they wanted. Usually, both parties are able to speak their piece in a calmer environment and everyone can move on. (Every once in a while you get blocked on Facebook and the actor tries to avoid you for a couple of weeks.) In the end, you’ve done your part and should continue to maintain a professional relationship, regardless of their response.

Moving on to the nuts and bolts of touring

When you start a new tour, you’ll have a couple of weeks of shop prep when you head up to the NYC area and get all the gear (speakers, console, com, processing, RF, cables, etc.) and put it all together.

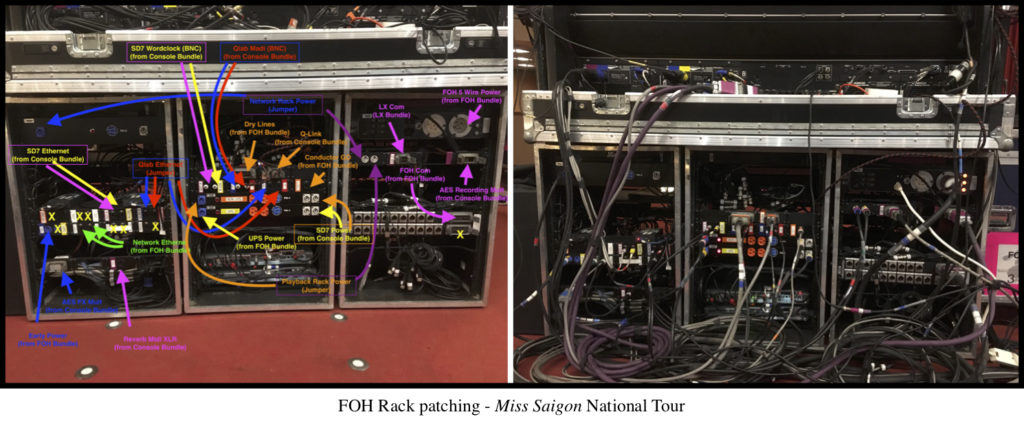

- Pay attention to learning the signal flow of the system. The better you know it, the easier it is to follow, isolate, and solve a problem when you’re under pressure.

- Color code cables and their ports. It takes far less time to look at a cable, notice it’s got green tape, and plug it into the matching green label in the rack, than it is fumbling around to read the label, then looking through the labels on the racks until you find the matching one. Spare cables are usually color-coded with YELLOW. This is usually true across all departments.

- Use a system for things that go together. I usually put a cool color with a warm color if I need to pair things up, with the cool color as the main and the warm as a backup (if applicable). So, BLUE and RED are a pair, PURPLE and YELLOW (in this case, not a spare), and then GREEN and ORANGE.

This also applies to cases. If you can, color code labels according to the case’s destination

- It’s quicker to say “all the PURPLE cases go to the pit” or “Everything with a PINK label goes to FOH” plus it’s easier for the local crew to remember.

- Also for cases, make short, clear names. On Saigon, we started with “AUTO/SM/FLY BUNDLES” which was a mouthful. Changing it to a more concise “COM BUNDLES” made it easier both for us to say and for the crew to find when we sent them looking for the case.

- The first couple of times you patch your racks, redo the bundling on the cables. If you have 6 cables in a single bundle and 2 go to one rack, 3 go to another and a single cable goes to a third place, break the tape on the cable loom back to where the cables need to go in their different directions and re-tape (with friction tape) what goes to the same place together.

As you start moving the show, another set of organizational skills comes into play. You develop a flexible routine, which sounds like an oxymoron, but the reality is that there will always be a few cities thrown in the mix where things just won’t be able to follow the usual plan. However, the individual tasks in your routine should retain a flow that you follow as much as possible.

- Make a checklist of everything you do during load-in. The more you move, the more you might get a sense of deja vu as you wonder if you’ve actually tested com, or you just remember doing it in the last city….

- Be consistent. Especially with cables. When you have twelve cable bundles coming to Ampland from seven different locations, load out will quickly turn into a mess if you try to unearth the one on the bottom first. When running cables on the load in, have an order. Say you always do FOH runs first (these are usually the longest runs, so it helps to get them first), then Crossovers (multiple), your Towers (Far and Near), next the Balcony Rail, then Pit (also multiple), and finally the shorter com runs (Automation, Fly Rail, SM Desk) to finish the day off. If this is how the bundles (almost) always get run out, it’s easy to remember that you simply go in reverse order on the out, pulling up what’s on top first and avoiding tangling them all together.

- Learn what you should do yourself and what you can hand off to the local crew. Personally, I prefer to plug in the cables at the racks myself. I’ve had enough times where a well-meaning local has plugged something into the wrong spot (or even upside down) and it ends up being quicker and less error-prone if I do it. Prep the complicated bits so you can give the crew simple instructions. Again, with cables bundles (so much of your life is about cables), I’ll unpatch and organize the ends of each bundle in various coils so I can point to one and say “that’s the next bundle you’re going to pull, it goes in the Tower Bundles box, and the other end is at the tower on stage left.” Then the crew can take it from there. Or when I would hang underbalc speakers, I’d go up to the balcony rail, measure out where I wanted things to go and mark it with tape. Then I could send the crew up and say, “hang one speaker at each tape mark” and tell them how to cable them.

- In that vein, make instructions concise and clear. There’s a delicate balance between too much information (hard to remember everything) and too little (not enough to get the job done). Pictures and diagrams can be helpful if you have the time, like having a pit layout for the local crew to look at so they can which player sits where. Clear labels are a must. Re-sending a local for a case with an ambiguous name or getting a wrong case because names are too similar is frustrating and wastes time. A name could make perfect sense to you, but might not to the local crew who’s seeing your show and organizational structure for the first time. Learn the phrases that locals are used to. Pay attention to your crew members who have been out on the road longer and what terms they use. Most crew members know if I say “This cable is a half box coil, cinnamon bun,” that means I want the bundle coiled up in one half of the case, making almost a spiral to fill up the center of the cable coil as well, which looks like a cinnamon roll. Or in the truck, I’ll tell the loaders to “ninety” something when I want to rotate a case 90 degrees or “as is” if it’s on the truck in the correct orientation, and then either “driver” or “passenger” to tell them which side of the truck it goes on. In situations where something has to flip upside down on top of another case, you use “wheels to the sky” (or in some cities “wheels to Jesus”).

- If you find that local crews across multiple cities are consistently having trouble completing a certain project, take a look at the instructions you’re giving them. True, some people don’t listen or don’t understand what you’re asking, but those should be exceptions. At some point, the information they receive is the common denominator and that’s what should be tweaked until you figure out the best way to explain it.

- Never ask your local crew to do anything that is unsafe. If you wouldn’t do it, you shouldn’t ask them to. Also, if you’re willing to hop in and help them when you can, they tend to like you better than if you just stand there giving orders.

Finally, some general housekeeping tips

- Keep things neat. Clean up after yourself, try not to put your cases and gear in other people’s way (if you can). And stay on top of this as you’re loading in. It’s a lot easier to lay all your bundles neatly at the beginning of the day than try to clean up a rat’s nest of cables currently forming its own mountain (which always just happens to be on the pathway the actors will need to use).

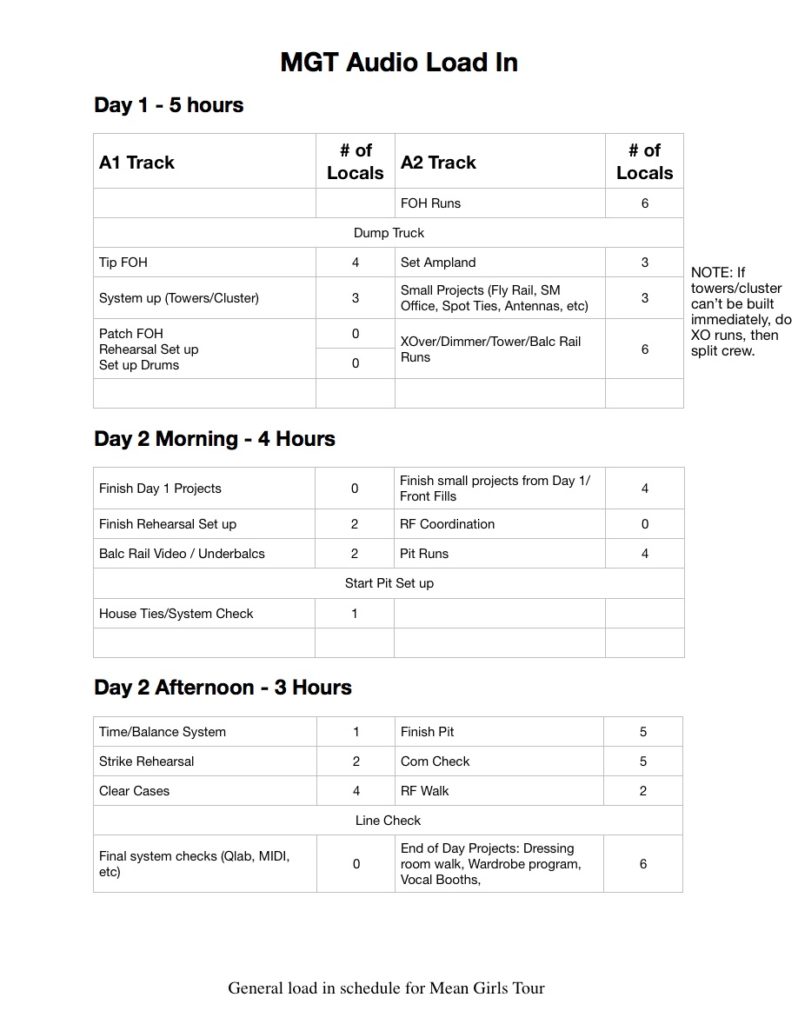

- Keep load in priorities in mind. As the A1, your focus is making sure everything in your department is progressing as on schedule as possible, and you’re in a good position to get the system up and ready for the show. As the A2, your job is to set up the infrastructure of the show and be ready when the A1 calls for something (she’s ready to power up FOH, check the mics in the pit, turn on the speakers to check the system, etc).

- Set realistic expectations and be aware of the big picture: I’ll plan to set up FOH early in the load in so I can patch it by myself and send the entire crew to the A2. Then she can do all the long cable runs which require more people. Then we split the crew so I can build the towers and cluster and she can get some smaller com projects set up. All of these jobs have to get done for the show to happen, and if we can alternate big and small projects, trading off the crew, we’re always able to work on something and keep moving.

I’ll say it again: if you follow nothing else on this list, don’t be an idiot and don’t be an asshole. Some common sense and a positive attitude go a long way in an industry that is so much smaller than you think.