We all like to think we’re absolutely indispensable, especially in the theatre world. There’s the old adage “the show must go on,” so we push ourselves to get tours into theatres where they barely fit, come to work even when we’re not feeling well because who else can run the show? Once, an actress asked what the A1 and A2 would do if one of us were sick. I told her that whoever’s not sick would mix the show, so she asked what happened if we were both sick. I replied, “then whoever’s less sick mixes with a trashcan at FOH.” Thankfully neither of us ever had to do that, but everyone on the road has a war story of doing a show despite illness or injury, bragging how quickly they came back or how stoically they soldiered through.

Trying to fit the old tour life we knew into a new landscape where Covid dictates so much have proven challenging to say the least. But some good has come from it: now more than ever, we’re focusing more on our physical health. Which is wonderful, and long overdue. However, sailing in uncharted waters leads to so much uncertainty in our lives. That constant stress takes a toll on the mental health of the company. We’re on rigorous testing schedules that race against the efficiency of an ever-evolving virus that threatens cancellations or unexpected layoffs if enough people in the company test positive. Before 2020 most of us would have cheered some unexpected time off and made plans to relax, but now there’s a nagging worry in the back of our minds that our entire industry could shut down again or our show could close for good. We find ourselves half tempted to stay locked in the hotel room in the hope that somehow that will keep a positive test at bay, all the while knowing that our quality of life will suffer drastically if we try to avoid each other completely.

We’re now at a point where being indispensable is a liability, not only to the company but to our own mental well-being. Even more so for the handful of company members who have become linchpins in a Covid world: people that, if they test positive and have to quarantine, have no replacement or understudy onsite to cover, and the show will have to shut down until they can return to work. In most cases, there’s someone, somewhere that could fly out to the tour to cover, but even that would involve at least one or two canceled shows.

At the beginning of January, I ran into both of those situations. Mean Girls had an outbreak of cases and had to cancel a week of shows, which had already happened on a handful of other tours. I found myself with some unexpected time off, but that didn’t last for long because our industry is a very small one. On my first day off, I got a call at 9 pm asking if I could leave on the first flight the next day so I could fill in for the A1 on the My Fair Lady tour, and Tuesday at 10 am I walked into load in to help the A2 get the show-up and running.

This was a job that brought a lot of perspectives. It was a d&b main system and Helixnet com, neither of which I’d toured, and a Yamaha PM10 console, which I’ve never touched before (I have worked on Yamaha consoles, and thankfully that knowledge of the software transferred!), plus a design team that I’d never worked with before. Walking in, I’d toured for long enough that I was able to get the general lay of the land, and the A2 and I worked through setting up FOH and getting the system timed with a few phone calls and emails to design and the A1 to make sure we had the right patches and were getting reasonably close to the original intention of the design.

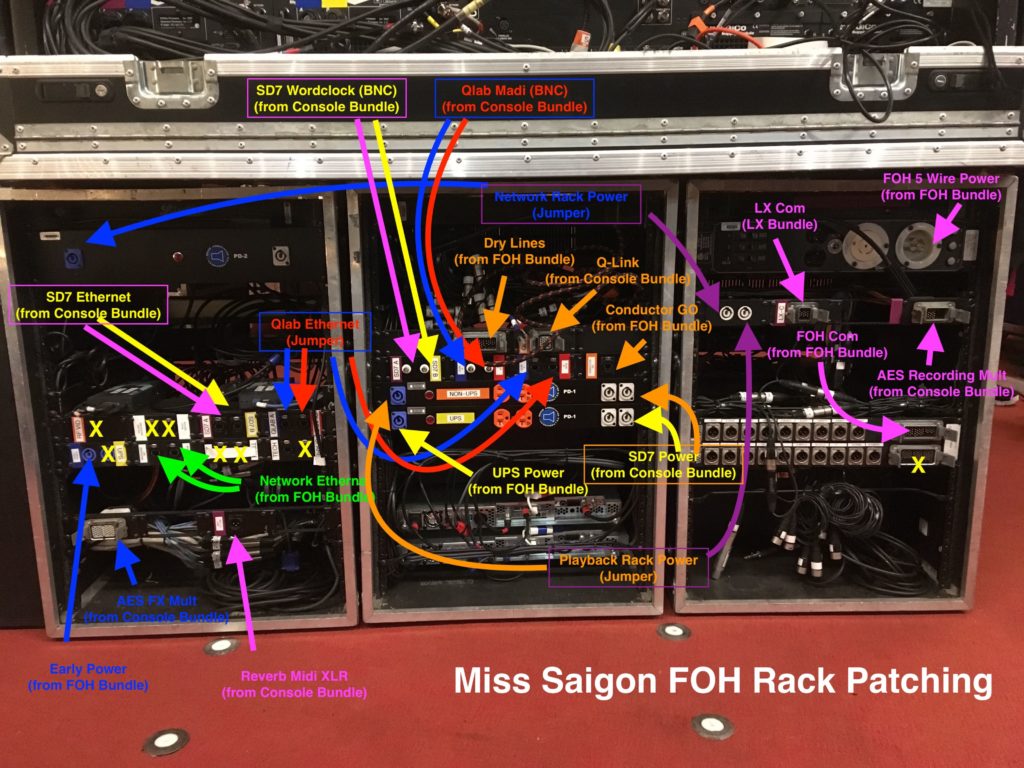

It was gratifying to see that I’d come far enough in my career that I could take unfamiliar gear in stride or at least know who to ask for help. It also showed me the gap between what we know as someone who runs the show constantly, and what a fresh pair of eyes actually see. Taking that back with me to Mean Girls, I’m starting to covid-proof my system to the best of my ability. So far I’ve added better labeling and color-coding to my FOH setup, taking more pictures of what things look like, and creating a Dropbox folder that I can send someone a link with most of the pertinent information they’d need to load in, run, and load out the show.

Luckily, this leans into one of my strengths. If you threw a dart at a collection of my blogs, you’re almost guaranteed to hit one that either mentions or completely focuses on some kind of paperwork: scripts, console programming, venue advances; I love a solid set of paperwork and some detailed documentation.

One of my projects on the post-Covid version of the tour was creating documentation of the show and my stint at My Fair Lady gave me a better idea of what I want to include:

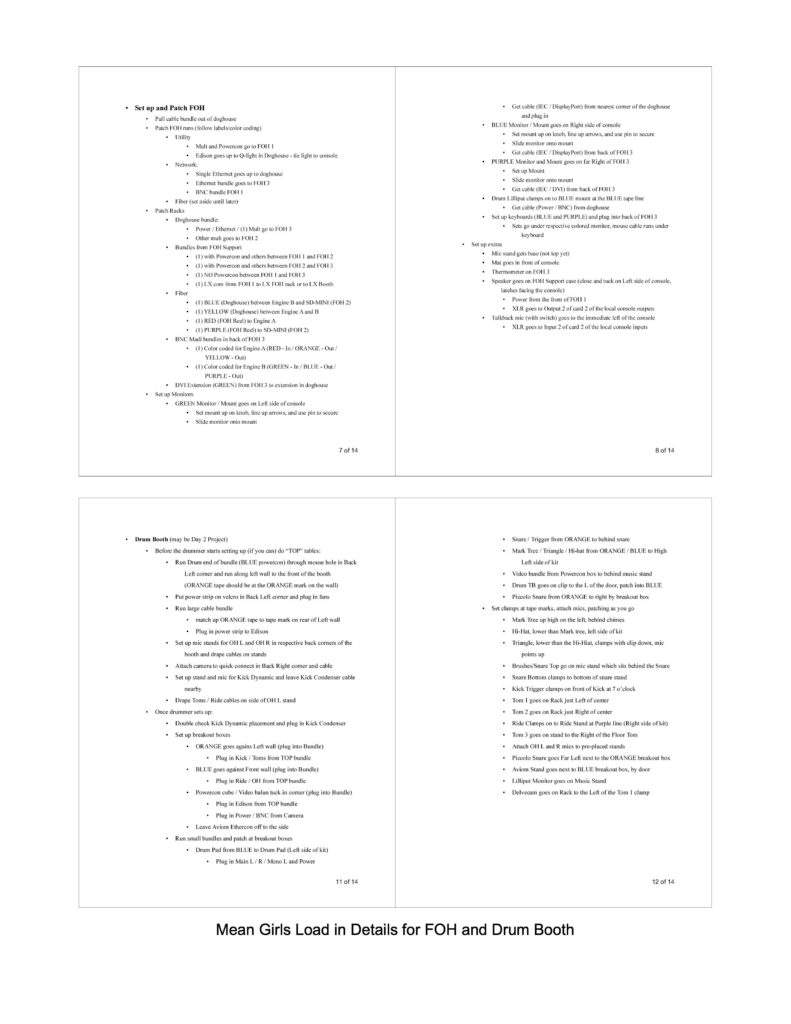

- Detailed Load In and Load Out track sheets: This includes which cases things are in, details I need to look out for, how projects get put together, etc.

- A “How to” of my power up and shut down process at FOH pre and post-show.

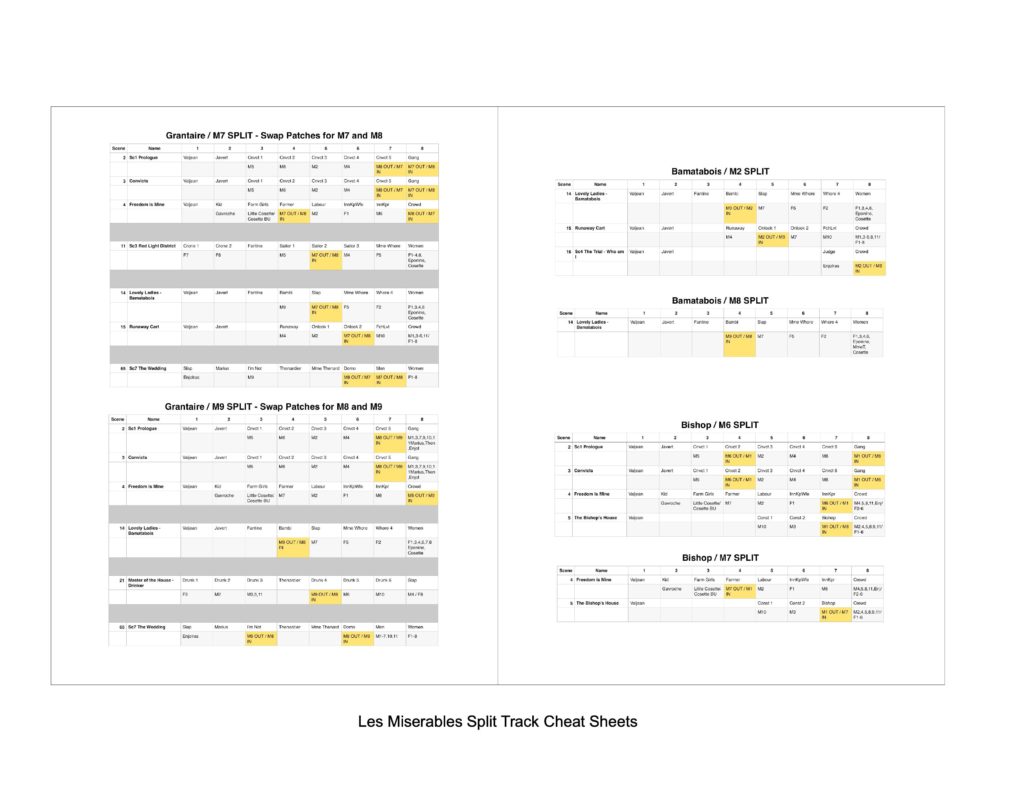

- Control Group (DCA) Assignments: A spreadsheet with details of who’s on what fader for each scene or notes if there are common split tracks (on Les Mis, there were featured roles like the Bishop or Grantaire that an ensemble member understudied, but would then go back to their normal show track. So the swing covering the person out, and the featured ensemble member would essentially “split” the two-track, hence the name.)

- Case List: A general overview of the contents of each case. Fun fact, this also makes it easier to do a manifest if you go to Canada, where they require you to document everything that’s in the trucks for the border crossing.

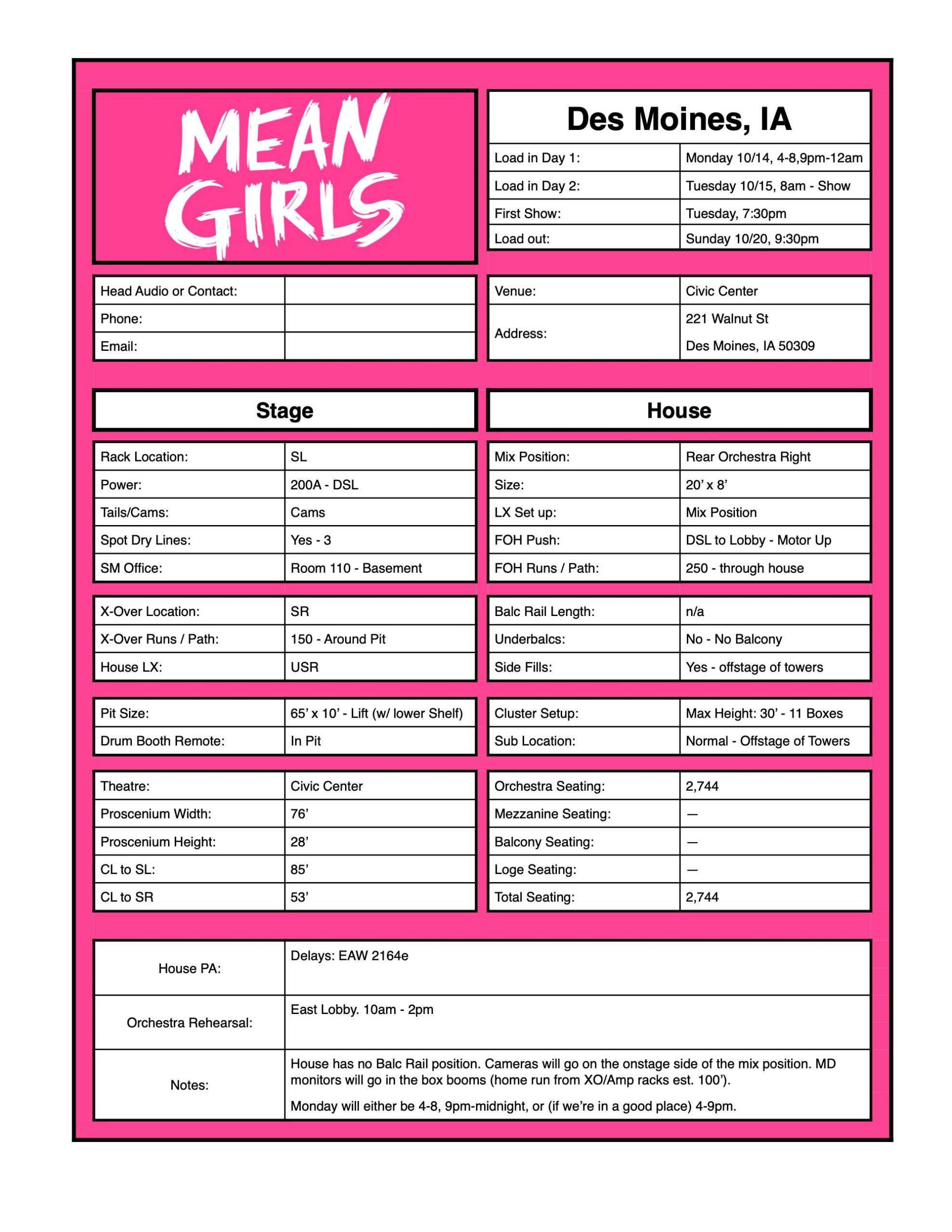

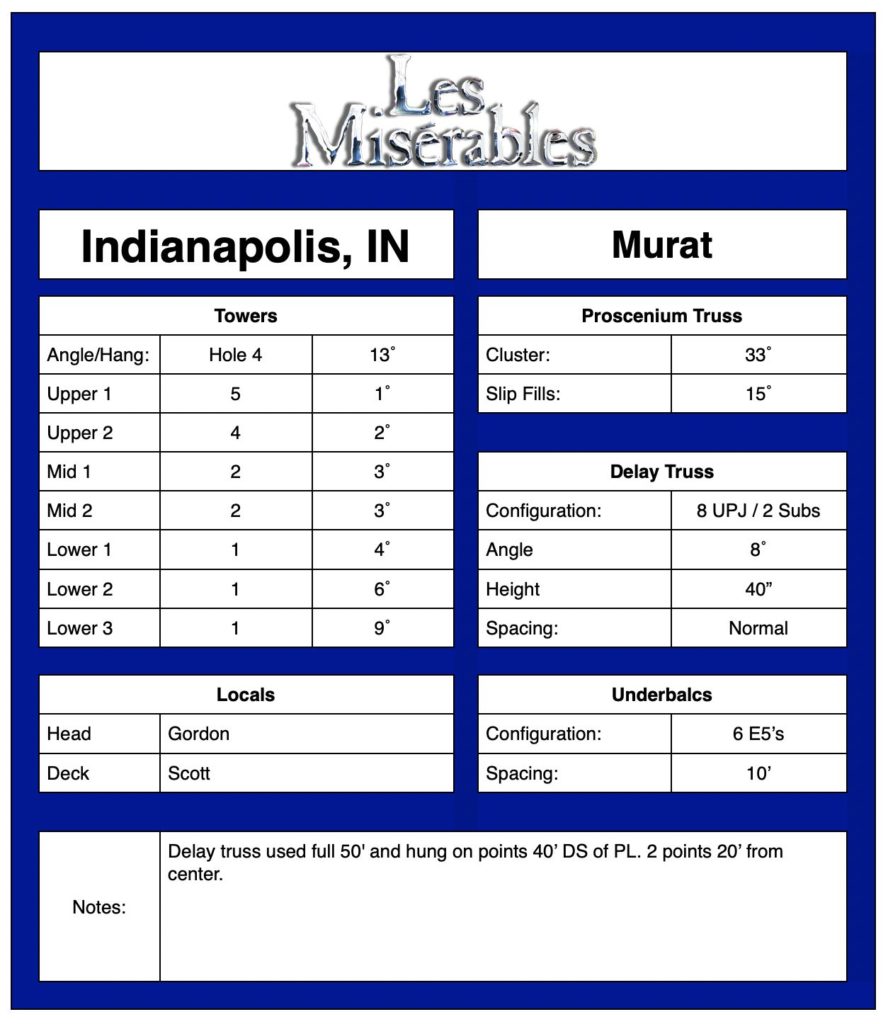

- Advance Sheets: Details about the venue showing where the plan is for racks, cases, cable runs, etc as well as what bits of the system (how much of the cluster I can hang, if we’re using underbalc speakers, etc) we’re planning to use.

- Cheat Sheets: In addition to the Advance, I’ll sometimes make myself a cheat sheet so I have one easy reference for splays for an array, angles on speakers, spacing for underbalcs, etc. This is something I’d put together and send to someone if they had to load in for me.

- Mixing Scripts: I have two versions: one that has all of my annotations (where cues go, CG/DCA assignments and notes), and another that’s blank except for the script so someone else could put their own notes in.

- Mix Video: I record a show that has four different video feeds: the stage, the conductor, an overhead view of me mixing, and a shot of my cue light. That way someone has a reference of exactly what I do during the show, as well as a reference if I take cues off something happening on stage, the conductor, or the cue light.

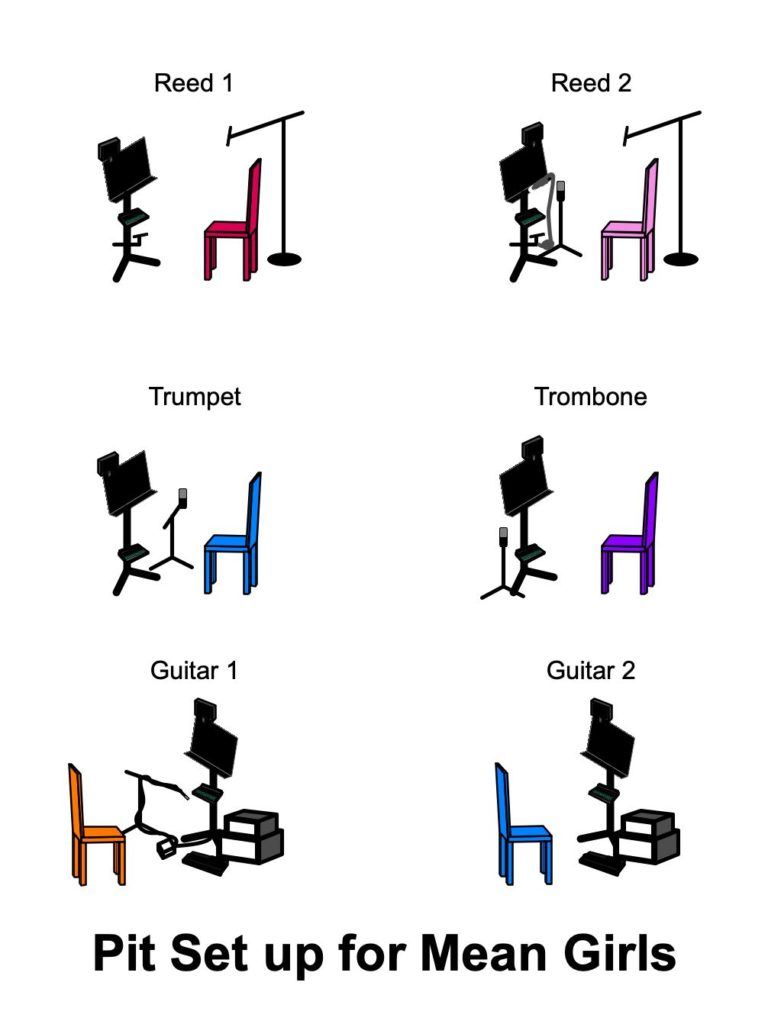

- Visual Aids: This might be pictures of the FOH or Pit set up, drawings of the stage, anything that might help someone visualize what’s happening. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

For some, this sounds like overkill, but I find peace of mind in the idea that I might give someone too much information, but hopefully never too little. I also have a lot of practice doing this kind of documentation because it’s similar to what I’ve done for some of the shows I’ve left, specifically those where I didn’t have much time with my replacement to help train them. The only difference is that this would be a temporary replacement with who I’d have absolutely no crossover, other than answering questions on the phone as I sit in a hotel room in quarantine.

At this point in the touring world, it’s no longer about job security, it’s about sustainability. Eventually, we may move to a point where Covid won’t shut shows down for weeks at a time, but we’re not there yet. Until we make it to that point, we all have to be prepared for the when — not if — of being the person who’s in quarantine. For me, that means lots of time typing on my computer so I can rest just a little easier knowing I’ve done everything I could to make my replacement and my crew’s life as easy as possible.