Recently there has been some press about how articles about female scientists are frequently deleted from Wikipedia, especially when compared to their male counterparts. As a casual Wikipedia editor, my initial reaction was anger and betrayal. There had to be something I could do about it. One of the underlying reasons behind articles disappearing resides in Wikipedia’s strict resource guidelines. Personal websites and aggregate websites are not accepted, and print media is preferred. Setting aside the fact that the male-dominated editor community enforces these guidelines with bias (that solution involves more women editors, which I have addressed in previous articles), there are rippling consequences for lack of representation. Then what is our solution? Write about women and gender-fluid folk. Interview them. Write reviews of their work You are seeing that solution in action, here, at SoundGirls.

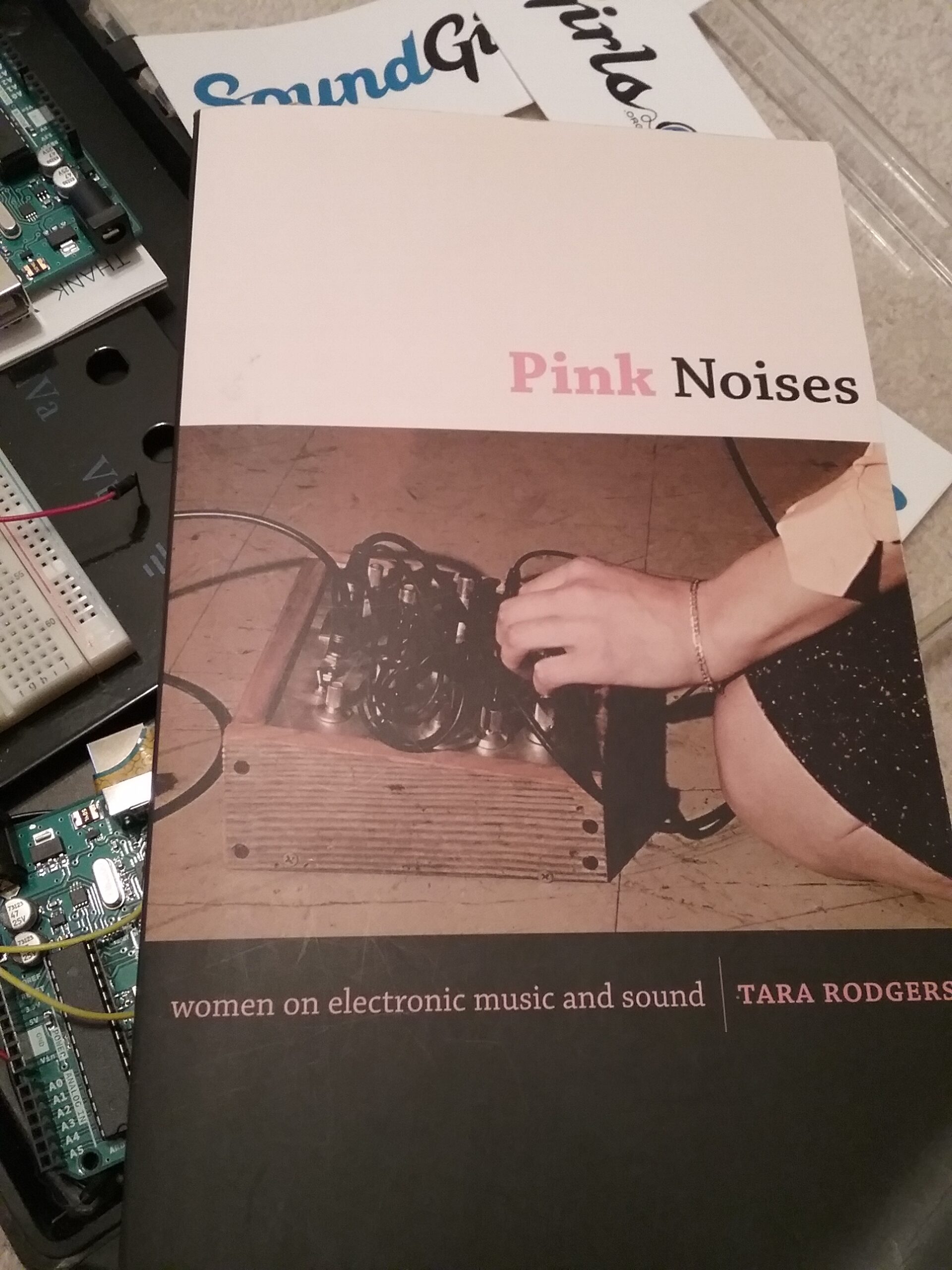

Dr. Tara Rodgers is also part of that solution with both Pinknoises.com and Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. I do not know exactly how this text came across my radar, possibly from stumping Amazon’s suggestion algorithm, but it called to me and my bottomless appetite for reading. Pinknoises.com, when it was active in the early 2000’s, was a collection of interviews curated by Rodgers focusing on women in electronic music. The book is formatted similarly and is a highlight reel of the website. It received the Pauline Alderman Book Award from the International Alliance for Women in Music in 2011.

“Pink noise” is a double entendre of sorts: referring to the association of pink and femininity paired with noise as a jarring a-musical sound, and pink noise as a broadband collection of frequencies with equal energy per octave. Each artist Rodgers interviews is an iconoclast in her own right, noise to the established system, and each has their own musical philosophy. While Rodgers does devote at least one question per interview to address the lack of diversity in electronic music, not one interview is stuck on that issue. In fact, several of the artists bristle at the question, angered by its apparent necessity and inclusion. The honesty is refreshing. These are artists who just happen to be women. Their work is what defines them, not their gender.

Before opening Pink Noises, I had not heard of any of the artists interviewed, but I recognized some of their male contemporaries. Their accomplishments are too numerous, too awe-inspiring to be kept a secret. This book needed to be published. From their hand’s synths were invented, software developed, movements revolutionized. And the interviews focus on the why and how. “What drew you to music?” “How does a piece get realized?”

Rodgers guides the interviews with an anthropological lens. Although this book was published in 2010, the answers are timeless and not based on one software or operating system. A reader from 2020 or even 2050 has something to gain here. What also gives Pink Noises depth is the diversity of artists picked for the collection. From Pauline Oliveros to Riz Maslen (aka Neotropic), they traverse the history of electronic music as well as the breadth of its expressions. They are from all over the world, there are both artists and engineers, and the work ranges from museum installations to nightclub sets. Rodgers bucks elitism and gatekeeping to archive what should never have been ignored in the first place.

Let this book inspire you to create your own masterpiece, but not just that. Let it inspire you to collaborate, to write, to share. Be inspired to update “normal” to include the diversity we know is there. Help others to make their works heard and seen, help them get recognition. We can and will cross the threshold of notability. This starts with us