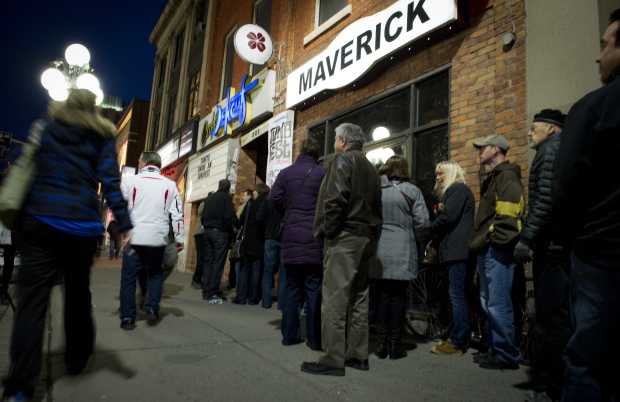

I worked for three years at a 310-capacity room in Ottawa called Mavericks. While to most readers that might seem small, it was the city’s mid-sized venue. Ottawa has a population of roughly one million. To get into tour lingo, it’s a B market. Most American & European tours that make it up to Canada skip Ottawa. They favour doing shows in Montréal and Toronto (even though Ottawa is barely a 45-minute detour) due to their larger populations.

Fortunately for me, a few Ottawa promoters have been working hard to put the city on the map, and we often had larger tours coming through. These shows would prove to be the greatest learning experiences for me, as they were often challenging – bands and crews were used to larger stages and separate FOH and monitor boards. Mavericks would often be the smallest capacity venue the tour would hit, which meant we had to make up for our small size with a welcoming attitude and well-maintained equipment.

When I started working as a tech, I mostly mixed local shows. These gave me the chance to get used to the room and gear, without having to deal with touring crews and their needs. As I got faster at running a soundcheck and better at working with different personalities, I started working on bigger shows.

Here are some of the lessons I quickly learned:

Know your Patch

If I had multiple touring techs using our snake and house board, and not using a festival style patch (i.e. all techs fitting their band’s patch to one input list). I had to re-patch as the show went on. With 15-minute changeovers and a crowded stage of equipment – think of five bands with three separate backlines and five different drum kits. I realized I should number my lines both at the snake head and microphone end. It’s no fun to be going through a mess of cables to find that fourth tom line as a touring tech is yelling through the monitors!

This brings me to my second point…

Set a Clean Stage

After an angry stage manager had kicked a 50-foot XLR cable off my stage for being improperly coiled, I realized I had to step up my clean stage game. When I first set up the stage, I make it a point to make sure I leave my XLRs coiled by the microphones. When I do changeovers, I make sure to re-coil lines as needed. Working more corporate-type events for an AV company also taught me to run cables in a safe way, as far away from performers’ paths as possible.

In short, I see a clean stage as one where cables are run behind the musician’s equipment when possible, and never in high traffic areas like an entrance. If I have to run cables where they can be tripped over, I tape down my lines with gaff tape.

Be Confident in your Skills

There’s a reason the venue or promoter hired you! The techs I look up to are friendly but self-assured, and always willing to help bands or touring techs without being overbearing. After seeing my employers give more shifts to the techs who followed those ethics, I tried to model my behaviour on theirs.

At first, I was often intimidated by the touring techs. I always remember the time I had one guest engineer push me aside (and I’m not small, at 5’7”) so he could show me how to properly EQ a metal kick. There was no reason for him to do this, as I was just setting up my mix. It was one of those five band shows with quick changeovers and little to no time to soundcheck. I was more concerned with getting monitors set for the band then establishing a FOH mix, which I’d work on through the first song. As I progressed as a tech, when faced with similar situations, I hold my ground and ask the visiting engineer to give me some time and space.

I see the touring/house tech relationship as symbiotic. The house tech(s) will set the stage, run changeovers and take care of the system while the touring tech should offer to help with patch and changeover. Having spent more time as a house tech than on the road, I have seen numerous touring engineers be rude to the local crew. It’s totally counterproductive to the show’s functioning for the techs to argue. Furthermore, you never know when you could run into someone again: many touring techs also work for venues or AV companies in their hometown. I found the best shows I had on the road were at venues where I had previously worked with the house tech(s). Because I had treated them well when they came through one of my venues, they returned the favour and were extremely helpful.

Unfortunately, I quickly realized that audio engineering is a male-dominated space and that some of these guest techs may not have worked with many women. Often, my skills were undervalued, and my opinion was disregarded. I don’t want to excuse these techs’ behaviour, but I also realized I didn’t have time to get into a full-blown discussion on sexism within the industry during changeovers!

Attitude

I strongly believe that being a tech often has more to do with attitude than skills. As a woman, it can be hard to balance self-assurance and ability without falling into the dreaded “bitch” category. When I hear people use that term, I assume they mean that a woman is seen as taking up too much space and being overbearing. I strongly disagree with both that word and that idea, but have also come to realize that arguing ends up being detrimental to the well-being of the show.

As an example: while out with a touring band, I had one house tech yell at me throughout my short soundcheck. The band was second on a package of four bands, with 15-minute changeovers. The house tech yelled at me for being too loud, going over my allotted time, and on and on. Now, I had just watched the house tech mix, and he was also occasionally hitting +3dB on the analog board. I also knew I wasn’t over time, as I had the set times and a watch beside me. I could have stopped my check to argue with the house tech, but I knew that wasn’t fair to my band. To be clear, I don’t think my existence as a female tech needs to be validated by a man. But I realized I just wasn’t going to be able to get through the set without assistance. I called over the tour’s head sound tech and asked him to stand beside me. He acted as a buffer between the house tech and myself and assured him I knew what I was doing and wouldn’t blow up the system. His presence is what allowed me to mix, in peace.

Quickly, I learned that if I wanted to succeed, I could not be afraid to ask for help. I have more respect for techs that, regardless of gender, aren’t afraid to ask others for room EQ tips, new microphones, mixing tips, etc. We all have different experiences, and we can usually stand to learn a thing or two! This last point has been particularly relevant for me recently, as I settle into working in Toronto and try to increase my skills.