As a mixer, I see all kinds of issues cropping up that originated in sound editorial. And with my background in sound editorial, I’ve surely committed every one of them myself at some point. Here’s a list of some common problems we see on the mix stage. Avoiding these problems will not only make your work easier to handle and more professionally presented, but it will also hopefully save you a snarky email or comment from a mixer!

Sound Effects With Baked In Processing

As soon as you commit to an EQ, Reverb, or other processing choices with Audio Suite, your mixer’s hands are tied. Yes, you may be making a very creative choice, however, that choice can not be undone and often processed editorial simply needs to be thrown out and recut to make it mixable.

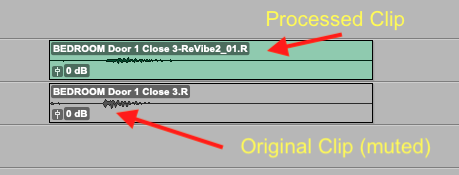

But what if you just have you present your creative vision in this way, be it for a client review or to get an idea across? In that case, your best move is to copy and mute the sound clip. Place the copy directly below the one you plan to process so it can easily be unmuted and utilized. In this case, your mixer has the option to work with the dry effect. Another alternative, if you’re dealing with EQ processing, is to use Clip Effects. Just be sure that downstream the mix stage has the proper version of Pro Tools or this information won’t be passed along.

How about if the sound has room on it, but you didn’t put it there? I’ve gotten handclaps that sound like they were recorded in a gymnasium cut in an intimate small scene. That’s just a bad sound choice and you need to find a better one.

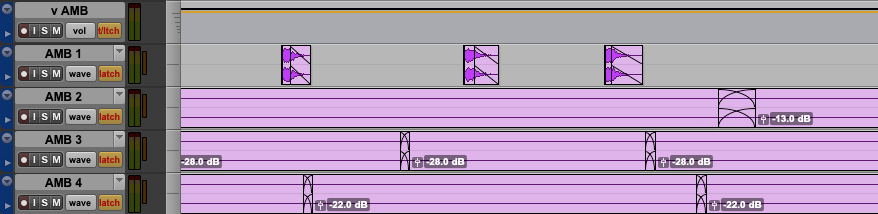

Stereo Sound Effects Used for Center Channel Material in Surround Or Larger Mix Formats

Sound editors, especially those that work from home, do not often cut in a surround sound environment. The result of cutting in stereo for a surround (or larger format) project, is the lack of knowledge on how things will translate.

One of my big pet peeves is when center channel material – actions happening on screen, in the middle of the frame – is cut with stereo sound effects. The result of, say, a punch or distant explosion cut in stereo when translated to the 5.1 mix is a disconnect for the listener. Ultimately, we as mixers need to go into the panning and center both channels to get the proper directionality.

Now, it’s not an impossible problem to solve when working in stereo. Just avoid cutting sound effects in stereo tracks that do not engulf the entire frame, provide ambience, or are outside of picture as a whole. Your mixer will thank you for it.

Splitting Sound Effects Build Between Food Groups

We have written extensively on the idea of using “Food Groups” in your editorial to keep things organized (see links below).

The dark side of this, however, is some editors can get carried away with these designations. The error to avoid here is to be sure anything that may need to be mixed together, stays together.

For example, if you have a series with lots of vehicles, it may seem to make sense to have a Car food group, as well as a Tires food group. The Car group would get the engine sounds and the Tires the textures, like gravel and skids. But when it comes time to mix, this extra bit of organization ends up making the job extremely difficult. If a car goes by from screen left to right, the mixer needs to pan and ramp the volume of those elements. If you group them all together in one chunk of tracks, it’s an easy move to group them. If you split them up among food groups, the mixer then has to hunt around for the proper sounds, then group across the multiple food groups. It’s simply too cumbersome. Not to mention that it takes the functionality of the VCA out of the picture. A solution, in this case, would be to simply have a Vehicle food group that encompasses all aspects of the car that could require simultaneous mixing.

Layering Random Sounds Into Food Groups

Speaking of food groups and functionality, the whole point of a food group is to be able to control everything by using one fader (VCA). That functionality also becomes void if sounds not applicable to that group are dropped in.

For example, if we have an Ambience food group with babbling brook steadys and a client wants all the “River sounds” turned down, the VCA for that food group makes it a snap. However, if an editor cuts splashes of a character swimming in that same food group, it suddenly ruins the entire concept. True, splashing is water, but that misses the entire point of the food group.

Single sounds layered in with long ambiences render the VCA useless

Worse yet, is when an editor simply places sounds in an already utilized food group because they ran out of room on other tracks. This only works as a solution for layout issues if you have an extra, empty food group.

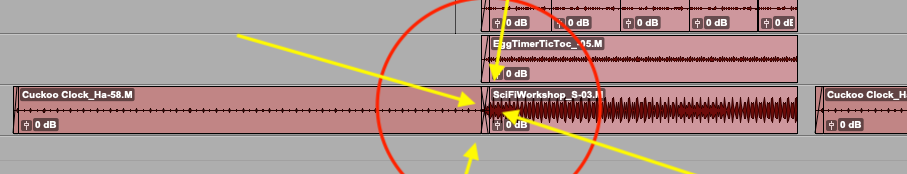

Breaking Basic Rules In Order to Follow Another

There’s a basic hierarchy to rules of sound editorial. Some rules you just can’t break, plain and simple. Like crossfading two entirely different sound effects with one another. That’s a mixing nightmare, one that simply needs to be reorganized in order to successfully pull off the job. But sometimes the breaking of these rules comes with the best of intentions. I have two examples for you.

In this case, the editor ran out of space in a food group and opted to use this crossfade, rather than break up the food group. It’s important to not only know the rules but even more important to know when to make an exception. In this case, there was the simple solution of moving this one sound into the hard SFX tracks, or simply adding a track to the food group (with permission from your supervisor or mixer), solving the issue and not creating any new ones.

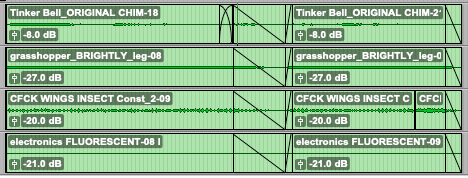

Here again, we have an editor with the best of intentions. An insect is on-screen moving in and out of frame from left to right. The editor thought that since the camera angle did not change, it did not warrant cutting the second chunk of sounds on a different set of tracks. Mixing this once again is impossible. As there is no time between the fading out and fading back in of the sound, there’s no magic way for the mixer to change an essential property, in this case, the panning. A proper understanding of perspective cutting would have avoided this issue.

Over Color Coding

Using colors to code your editorial is another topic we’ve covered extensively (see links below).

While color-coding your work is immensely helpful, here too lies a potential issue.

Let’s say you have a sequence in a swimming pool. There are steady water lapping sounds, swimming sounds, big splashes from jumping off the diving board. An editor may see this and think, it’s all water so I’m going to color all of these elements blue. The purpose of the color code is to delineate clips from one another to speed up the mixing process. When an editor liberally color codes their work one color, you end up with no relevant information at all. In this case, each of these categories of sounds should be colored differently from one another so that it’s obvious they are for different parts of the scene.

POOR LAYOUT FOR FUTZ MATERIALS

Materials that need special treatment, like sound effects coming from a television, need to stay clustered together within an unused food group or at the very least on the same set of tracks. I like to have my futz clusters live on the bottom-most hard sound effects tracks, color coding the regions the same to make your intentions absolutely clear. This allows the mixer to very quickly and easily highlight the cluster and set a group treatment, like EQ. Think of it as temporarily dedicating some tracks for this purpose and stair-step your work around them, being careful to not intermingle non-futz materials on those tracks for the duration of the necessary treatment, which is equally problematic.

Why go to the effort? If you sprinkle these materials throughout your editorial, it becomes a game of hunting around for the mixer to find what needs futzing. Odds are your mixer will need to stop mixing and reorganize your entire layout to fix the problem and make it mixable.

Bonus Issues

-

Leaving markers that have visibility and view settings baked in – the mixer clicks the marker and their entire session view is thrown out of whack.

-

Hidden tracks – you can’t count on the mixer to check the tracks bin. If you want it in the mix, make sure it’s shown when you save your session.

Some Further Reading on the Topics of Food Groups and Color Coding

SPEAK VOLUMES THROUGH WELL ORGANIZED WORK

DOWNSTREAM: VALUABLE SOUND DESIGNERS THINK LIKE MIXERS

LAYING IT ALL OUT THERE: WHEN A GOOD LOOKING LAYOUT IS ACTUALLY BAD

FIVE THINGS I’VE LEARNED ABOUT EDITING FROM MIXING

WRITTEN BY JEFF SHIFFMAN, CO-OWNER OF BOOM BOX POST