When I started mixing bands in-house at university I was terrified: I had so much technical stuff to remember, and then I was faced with a bunch of stony-faced strangers who wouldn’t even come and talk to me! They were going to hate me. If I had known then what I know now about interacting with bands (and event organisers, or any kind of client really) those first gigs would have been so much less stressful. It’s easy to forget that not many people outside of our job really understand what the role entails; it’s a bit of a dark art to them. The technical team can make or break a show, and that can make people a bit nervous about us. Once I realised that bands are like spiders: they are, on the whole, more scared of me than I am of them, I could approach things differently.

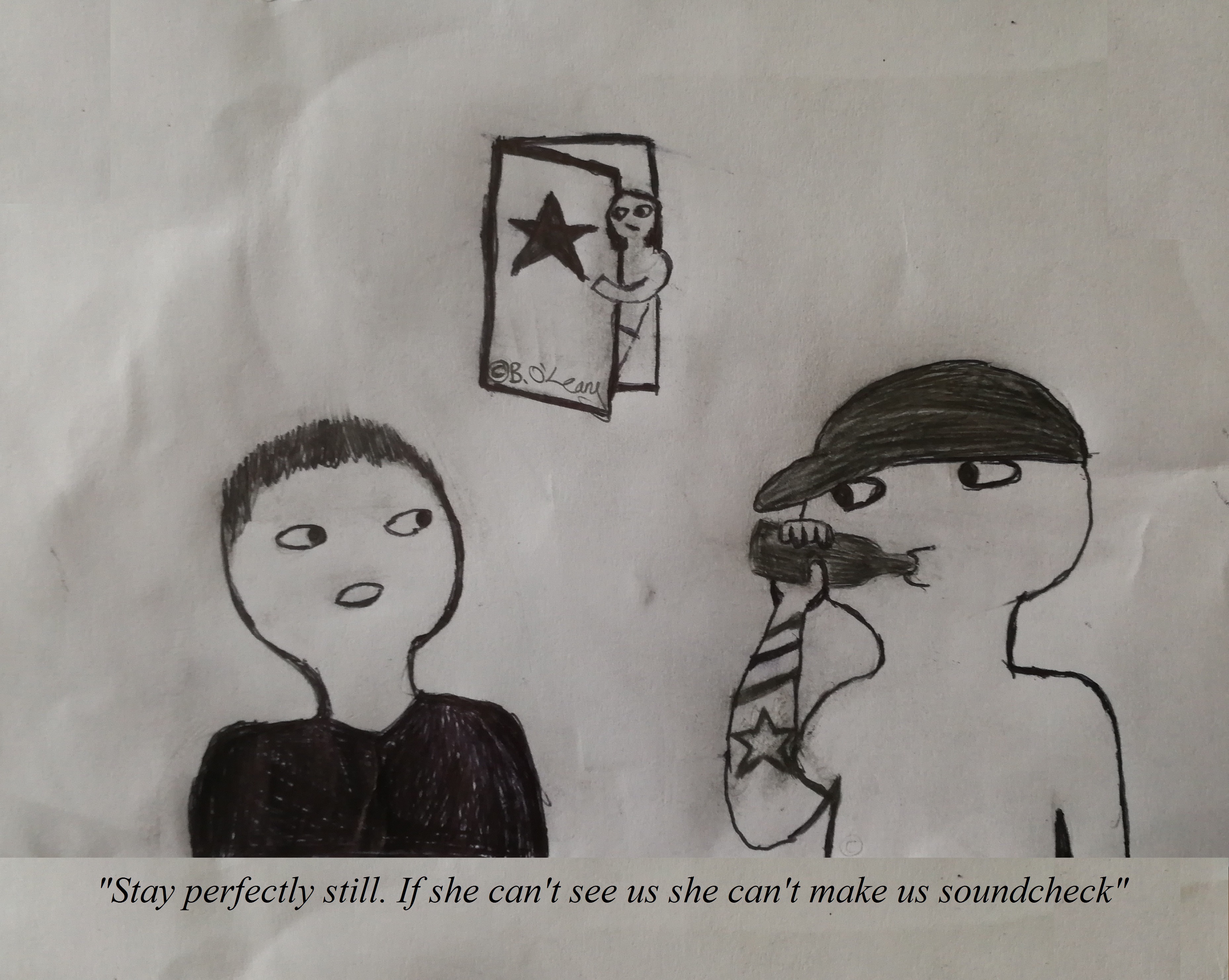

First off: don’t expect them to come to you! They may be affecting an air of cool by being standoffish, or they may just be shy, or a bit lost because they’ve just got out of the van after an 8-hour journey and are looking for the facilities… Take a deep breath, smile, and go and introduce yourself. Be ready with a pen and paper to note anything you need to know that wasn’t in the advance. The single best piece of advice I’ve ever got for mixing is to write the band members’ names down! If you’re on monitors, write it on their mixes, on FoH on their vocal or instrument channels. It’s such a simple thing, but using their names during soundcheck makes them feel that you really are paying attention, and if someone yells “I need more of Dan in my wedge!”, halfway through a song with no hand gestures, you stand a fighting chance of knowing who and where Dan is. Communicating with them properly from the start will help them to relax so they can concentrate on having a better show. You’re also inviting them to let you know about problems constructively, instead of giving you the silent treatment then complaining after the fact that it sounded bad.

The same applies to any live event: take the initiative to introduce yourself to the client’s point of contact (or ask the head of the technical team to introduce you if that’s more appropriate) and be confident! I come from a background where modesty and talking down your skills is the norm, and confidence is looked down on as boasting, especially if you’re a woman. It took me far too long to understand that people look to the techs for reassurance that the show’s going to go smoothly. You needn’t be arrogant, just be secure in your abilities. Clients often gauge how well things are going by looking to you; the knock-on effects of you appearing happy or worried are definitely noticeable.

When things go wrong, and they will don’t let the confidence fade. Technical issues happen, it’s how you deal with them that’s important. Take a few seconds to assess whether you can fix the problem quickly. If not, it’s time to swallow your pride and let someone know. If you realise you’ve made a mistake don’t ignore it in the hopes, it’ll go away. The earlier you own up to it, the easier it is to deal with. For example, if you’ve forgotten to bring something from the warehouse, you might be able to get it delivered in time for the show if you mention it at 11 am, but you won’t have a chance at 6 pm. You might get teased or worse for it, but it’s much easier to forgive and forget as long as it’s alright in the end. How you deal with problems gets remembered much more than what the problems were.

As engineers, we often tend to shut out the outside world and think only about the signal path when something goes wrong during soundcheck or the show. While it’s great to be focused, taking a minute or two to tell someone else can actually speed up the problem-solving process, or at least prevent a stressed and angry client because the music has stopped and you’re ignoring them. If there’s another sound person there, tell them what’s happening. Two minds are better than one, and at the very least they can go and smooth things over with the band or event organiser while you get on with troubleshooting. It can be very frustrating when an already patronising colleague steps in and “rescues you,” but in the long run, it’s more important that the show goes well than that you were the one who saved the day.

If you’re the only tech, calmly tell whoever’s in charge what’s going on, and roughly how long it will take to fix. No need to waste time on details unless they ask; saying you have a technical issue but you’re working on it is usually enough. Don’t be tempted to tell even a little white lie! You never know who used to be a sound tech in a previous job, and bluffing to them could do you a lot more harm than good. Clients don’t care that an XLR has broken, all they want to know is whether you can fix it, how long it’ll take, and whether it’s likely to happen again. Remember the Scotty principle: overestimate the time you need by at least 25-50% to allow for unforeseen complications. People are much happier if you’re back up and running in 20 minutes when you said half an hour than if you promised them it’d be done in 10 or 15. Don’t waste time apportioning blame either. It’s impossible to look professional while pointing the finger at someone else, even if it was their fault.

There’ll be times where you might think there’s nothing that sharing the problem will do to help, but you never know. Someone might have a quick and simple solution that just didn’t occur to you because you’re stressed or inexperienced, or the event organisers could open the community fair with the sack race and move your band’s set to, later on, buying you precious time. You won’t know until you discuss it. You might be surprised by how willing people are to help if it ensures the success of the show, and makes life easier for that nice sound engineer who was so welcoming and friendly when they first arrived.