What is a Sound Design Associate?

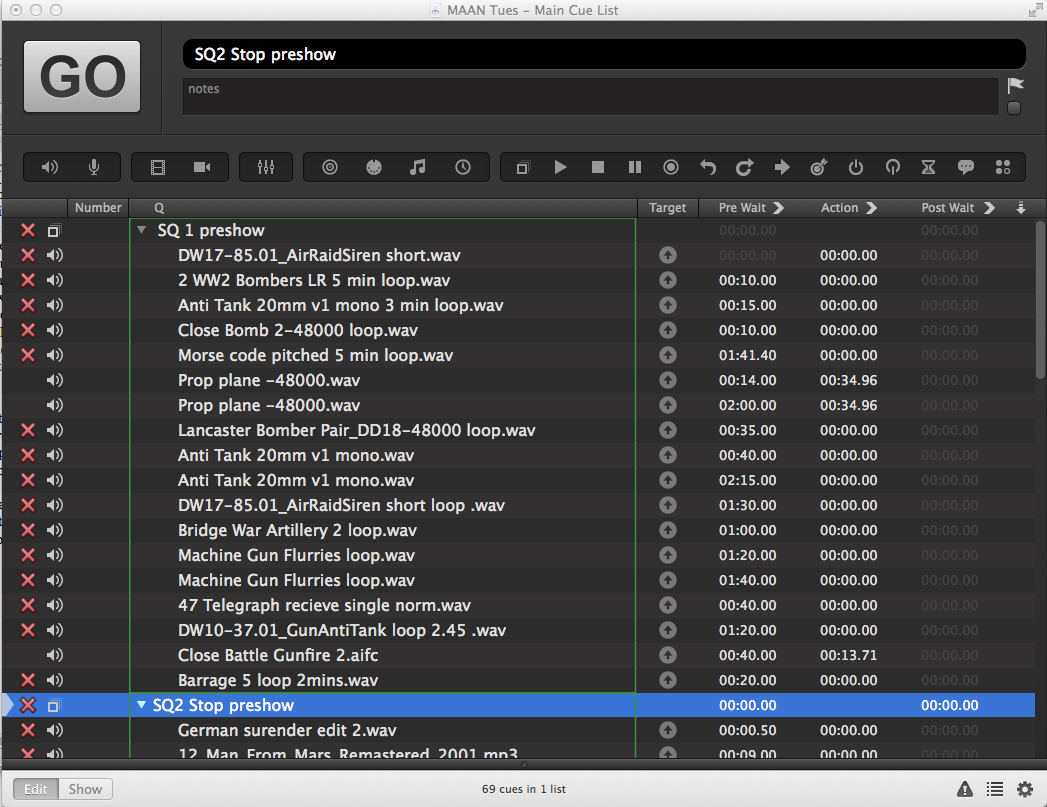

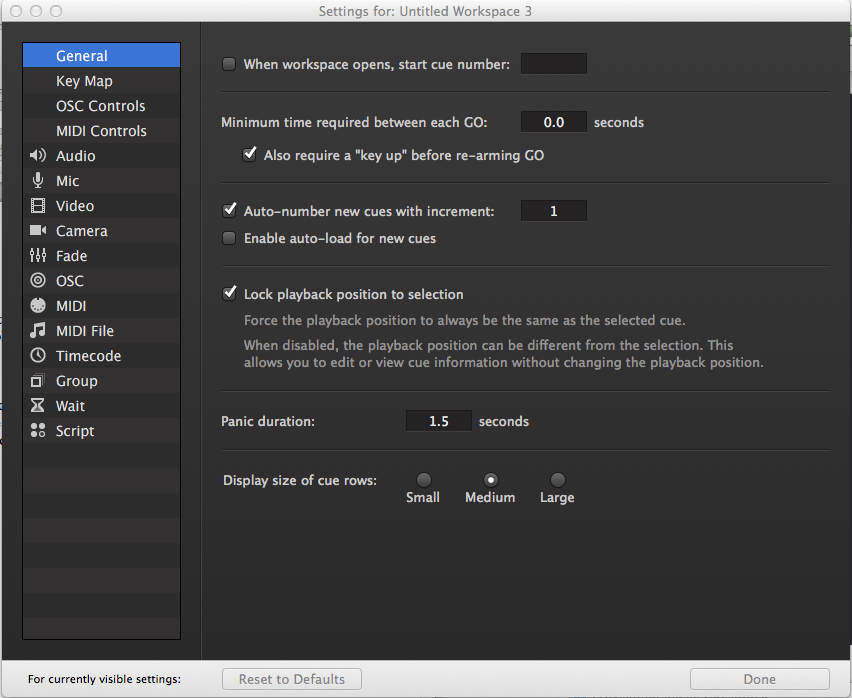

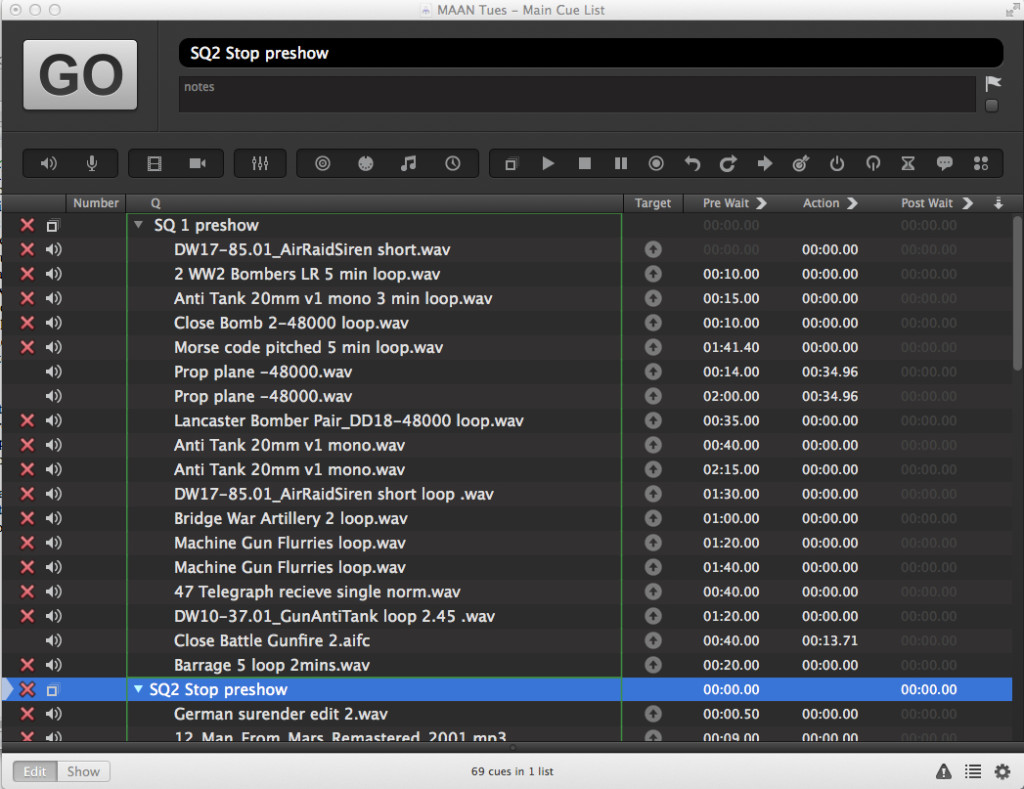

A Sound Design Associate works closely with the Sound Designer and Director, undertaking much of the work. It can include finding music and sound effects dictated by the Sound Designer and Director, maintaining the paperwork, and assisting the Sound Designer in cuing the show. The Sound Design Associate may also work with the Sound Board Operator providing instruction, and assistance in making changes to the cues during rehearsal.

Each designer has their way of doing things and being able to be the associate for more than one Sound Designer has been an invaluable education. It puts me in a unique and privileged position, as I get to see different techniques and how they are used by excellent designers. Did I mention I also get paid. It’s interesting to see how another designer programs a cue list, sets up a system, or interacts with the rest of the design team.

The role is very different depending on the designer I’m working with. Sometimes I handle all the paperwork and translate the designer’s ideas into a spec sheet for a hire company. Sometimes I’m taking care of the SFX while the designer is looking after the system, and the band or the reverse situation can happen. I tune the system and work with the operator on the desk while the Designer is creating the soundscape.

I have recently been the Sound Design Associate for John Leonard. I’ve been John’s Sound Design Associate on more than one occasion, and it is always an excellent opportunity to learn from someone who is well respected and has been doing this a long time.

My Approach to being a Sound Design Associate

I usually am hired as an associate when a Sound Designer I have worked with before has production periods that overlap, or if there is a big project that needs to be produced in a short time frame. Designers can hire an Associate, and they can take on more than one production. An Associate will be their representative and manage the designers’ interests in their absence.

There may be days of Tech or Preview that the Designer cannot attend and I will represent the Designer. In this case, the Designer needed someone to look after the show from Preview 1 to Press night. I went to a couple of run-throughs and I sat with John during tech to get a feel for Johns and Iqbul Khan’s (the director’s) vision for the production. I then took over the lead after preview one.

As an Associate, I think it is important to remember this is not my show. I may have artistic input, and if the director asks for something, I will work hard to make it happen. But I always keep the designer aware of any changes I have made. When working with John, he always gives me a free hand, but I do remember I am representing the reputation of another designer as well as my own.

For the recent production of Macbeth, there were a lot of changes after the first preview. John trusted that I would make the necessary changes and also keep him in the loop, providing detailed notes. Although being an associate isn’t the lead role in the design process I find learning from and being exposed to different techniques a deeply satisfying experience.

More on the job duties of a Sound Design Associate