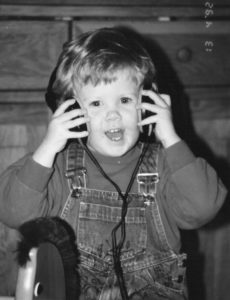

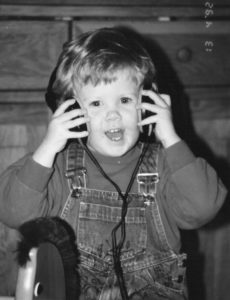

Daniela Seggewiss can’t believe that she has been working in Live Sound for ten years, because time flies when you are doing what you love. She initially caught the live sound bug when she was 13 and attended her first concert.

Daniela Seggewiss can’t believe that she has been working in Live Sound for ten years, because time flies when you are doing what you love. She initially caught the live sound bug when she was 13 and attended her first concert.

Daniela grew up surrounded by music, with music always being played around her house and she learned to play piano and drums, but she never could put her finger on what fascinated her about music. Until “I visited my first concert (One-Day 70ies Rock Festival – Sweet, Slade, Suzi Q, Hollies). Seeing that technical side of live music was the missing piece of the puzzle. I remember the one moment I realised I wanted to work in audio. I was standing next to monitor world watching crew, band and audience interacting with each other, that magic moment when music connects people and lets them forget their troubles. I knew there and then, age 13, that that’s what I want to be when I grow up, I wanted to be part of creating that magic. Following that fateful moment, I spent my time figuring out what career options there are in audio and how to make it happen for me.”

Her family was not quite sure how to deal with Daniela’s choice for a career, mainly as they had no idea what it meant to be a sound engineer and could only imagine the world as one of Sex, Drugs, and Rock n Roll. They did their best to support Daniella, while her teachers and career advisors in high school tried to stir her into more conservative alternatives.

Her family was not quite sure how to deal with Daniela’s choice for a career, mainly as they had no idea what it meant to be a sound engineer and could only imagine the world as one of Sex, Drugs, and Rock n Roll. They did their best to support Daniella, while her teachers and career advisors in high school tried to stir her into more conservative alternatives.

After finishing her A-Levels (high school), Daniela would apprentice as an event technician at a German national broadcasting station, learning about sound, lights, and rigging. This provided her a solid foundation in audio knowledge and stagecraft. She would eventually start out in audio taking care of the live sound for WDR’s (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) events in Cologne, Germany.

“Our team of three handled live audio and projection for every in-house event from planning to overseeing or operating the event itself. The events ranged from conferences to literature readings, and award shows to orchestra and big band performances and the occasional jazz or rock show.”

She would spend her summers working in Ireland for a festival, as an audio engineer on the second stage and the main stage audio tech. “My day started midday with the 2nd stage soundcheck followed by the gig and me running to the main stage to make the load in for the evening gig.”

Daniela would eventually leave Germany, to study and work in Leeds. She is a registered freelance sound engineer and was able to work in venues throughout Leeds. Rotating between four venues, with different size rooms from 100 -500 capacity. More often than not, she was the only tech working the gig, doing monitors from FOH and assisting the bands with the backline.

“The venue I spent most my time was the Cockpit in Leeds, which had three rooms in three arches under a railway bridge with aluminum stuck to the arched ceiling, literally a gig in a tin can. A shift in there would involve several power cuts, water dripping off the ceiling and stage invasions by the whole audience. After surviving that nothing a gig throws at me nowadays takes me by surprise.

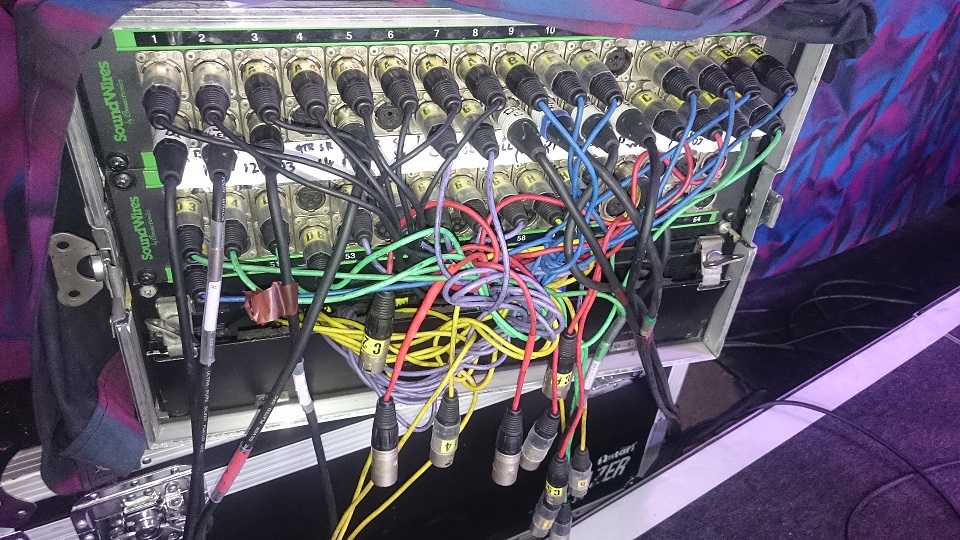

The Cockpit main room had a monitor desk, and most engineers did not like mixing monitors there, so I got that shift regularly and figured out quickly that I prefer that side of the multicore.”

Working at those venues, led to working with a local music festival, Bingley Music Live. It is a three-day, 15,000 capacity festival. She started as 2nd stage audio tech and worked her way up to main stage monitor engineer.

She currently works mainly as a freelance monitor engineer for the bands The Sweet and Opeth. Her year fills ups quickly between the two groups. She fills in the gaps with festivals and local gigs in Leeds.

She currently works mainly as a freelance monitor engineer for the bands The Sweet and Opeth. Her year fills ups quickly between the two groups. She fills in the gaps with festivals and local gigs in Leeds.

In 2017, she finished her BSc from Leeds Beckett University (Hons) in Music Technology, which has increased her knowledge of recording. She continues to learn by taking part in manufacturer training, d&b, Shure, Midas, etc. to make sure she stays up to date with the newest technology.

Her long-term goals are to start working with sound companies, so she can work her way up to working on larger-size tours. Although she does enjoy the medium size productions, being part of a small team that is family. And for now, feels that she could Mix Bands and See the World forever.

What do you like best about your job?

It’s two things for me.

The touring family & seeing the world! The friends I’ve made on the road from as early as that first concert are family to me! The part I like best about these deep friendships is that it does not matter how often we see each other, whenever we do, we can pick up right where we left off, and it feels like we haven’t been apart at all! I have “family” all over the world now, which is very handy considering I love to travel, too.

My family always traveled a lot. We own a campervan and would just go to the coast for a weekend. I always loved going on trips, exploring new places, meeting new people. Now I get paid to do that.

What do you like least?

It is the travel pace that I like least. I don’t even mind long flights too much, yet anyway. Give me another ten years, and I’ll probably hate them, too. But for now, it’s not having enough time to explore a gorgeous part of the world due to the brief time we spend in one place. I can tell you my bucket list of travel destinations is becoming longer and longer instead of getting checked off.

What if any obstacles or barriers have you faced?

The most significant obstacle for me was to find the way into the industry, especially into the rock’n’roll side of things, as there was no clear career path that I could follow and come out as a sound engineer.

I was very lucky to make connections early on with a network ever-expanding. However, even with some contacts, I felt like I did not have many options after finishing school as there are no sound companies in or near my hometown.

However, working through these obstacles confirmed that I was really passionate about becoming a sound engineer. And my way through the industry starting in broadcasting, followed by tiny clubs to medium venues and finally festivals and touring is exactly the “education” every sound engineer should experience. You have to grow in the industry! It is a hands-on job that has to be learned through hands-on experience.

I know there is still a lot of discrimination happening in this male-dominated industry. Either it never really happened to me, or I just didn’t care.

The local crew that thinks I must be the merch girl, just makes me chuckle nowadays. However, I have encountered local engineers, who thought I didn’t know what I was doing. In most of those situations, my touring crew family was more upset by the situation than me. It was only encouragement for me to show these guys that I know exactly what I was doing. And the band gave me the thumbs up at the end of the show was the best thing to shut these people up.

How have you dealt with them?

I feel like I just run through any wall. It was in my head that I would be a sound engineer, so any dead-end or obstacle was ran over.

Thinking about it now I realise that there were a lot of “No’s and “You cannot do that” involved, but I was so determined that I just kept going until I found a “Yes.” I came out the other end stronger and even more determined. So my determination and passion for this job help me with all the obstacles.

Advice you have for other women and young women who wish to enter the field?

Never give up! Be persistent.

Your best shot is to get to know sound engineers in your area, your local venue. I know this is the cliche answer. Networking! It is still weird for me to know to advertise myself and network to get my name around but that is where jobs come from, at least as a freelancer.

What helps me is to remember that we are all tech geeks and love to talk about it. Also, most engineers, however big their current gig might be, started out exactly where you are right now and provided the timing is right, are happy to give you advice!

As there is no clear, academic career path to become a live sound engineer, persistence, and professionalism, from the beginning is the key, as you never know which one of those 1000 people you talked to about sound might get you your first/next job. It was the monitor engineer I met when I was thirteen that got me my first job in a venue when I moved to the UK, ten years later.

Must have skills?

Such a simple question it seems but oh so complex.

The big picture:

Technical understanding – managing all those buttons

Music – it’s all about the music, you have to have a feel for music to understand the musician’s needs and requests and translate that into technical terms.

People – in my opinion the skill that’s the reason you get/ lose you the job

You’ll spend a lot of time with your band & crew so be easy to be around.

Especially as a monitor engineer you are working with people and need to be able to understand them almost on a psychic level, translate whatever they throw at you, in context of their daily mood, to a sound.

On a more practical level, it has to be Tidiness!!!

A tidy stage doesn’t only look good and professional but also you make your life so much easier for changeovers and fault finding. And this applies to 50 cap bar gigs to arena shows.

What other jobs have you held?

I am proud to say that I have managed to work as a sound engineer all my adult life. I was lucky enough to make some important connections early on and had that little bit of luck to be in the right place at the right time, so whenever one job opportunity ceased another opened up and I grabbed it tight and did not let go.

Do you ever feel pressure to be more technical than your male counterparts?

Not really. I am German and a perfectionist, which makes for a highly efficient combination. I demand a lot from myself. So no male counterpart, may he be oh so ignorant of my skills, has ever topped the expectations I have towards myself.

Is there anything about paying your dues you wish you would have paid more attention to that came back to haunt you later in your career?

On a more general level. Maybe. I wish I would have been more in the moment in the past couple of years. So many great things happened and kinda just flew past, again coming back to this rapid pace of life. I am proud that I have grabbed every opportunity that presented itself to me if anything it has been my private life that had to pay the dues so far.

I actually regret not continuing to play music regularly … I can still play a bit piano, taught myself some chords on guitar and love playing drums but I wish I would have continued to improve my playing … well, it’s never too late for that I guess.

Favorite equipment

I love DiGiCos. I seem to agree with their workflow.

I tour with a SD9 whenever I get the chance, and since I first used one, it felt like any given function I was looking for was exactly where I thought it would be.

I also always carry my RF Explorer which saved me and my IEM loving artists several times.

Parting Words

Keep calm! It took some club shows with power cuts and over-enthusiastic young bands knocking the PA over to teach me always to keep calm.

Keep calm! It took some club shows with power cuts and over-enthusiastic young bands knocking the PA over to teach me always to keep calm.

I bought my RF Explorer after getting an Arabian prayer through a GTR wireless, luckily only mid soundcheck. I did not want to take that chance ever again though.

Thinking outside the box.

The heaviest thunderstorm I have seen to this day at an outdoor gig in the Czech Republic taught me to think outside the box and just make it work with whatever you have available. That day the whole stage & backstage was flooded. But in good old “the show must go on” fashion we found as many towels as we could in an attempt to dry the stage and played the show with pedalboards on towels. Having learned a lesson, we played a show in Norway right after heavy rain with all pedalboards and wireless in zipper bags.

In the end, it all comes down to the ability to make it happen, which in my opinion is one of the main characteristics of the live sound / live concert industry. There is no second chance. We have the one chance to get it right so if something goes wrong we look around and use whatever we can find around us to make it happen!

Sennheiser & Neumann is seeking one member of SoundGirls to intern with the company during the 2019 AES NY show. Interns will need to be available from Oct. 15 – 18, 2019

Sennheiser & Neumann is seeking one member of SoundGirls to intern with the company during the 2019 AES NY show. Interns will need to be available from Oct. 15 – 18, 2019