Teaching the Next Generation of Audio Engineers

Life hardly ever takes the simplest route. Many in the field of Audio embody this sentiment. When I first moved to the Nashville area from the West Coast (I live in neither location now), I joined the Nashville Chapter of the Audio Engineering Society on Facebook, and as soon my request to join was approved I received a friend request. I am no social butterfly and was surprised by the notification. Audio Instructor and Engineer Jill Courtney noticed that another female Sound Engineer had joined her beat, and that was reason enough for her to connect. However, in getting to know Jill, I learned that it is natural for her to mentor and support her sisters in arms. In the spirit of #breakingtheglassfader, I thought I would get Jill to share some of her secrets of teaching the next generation of SoundGirls.

What is your current job title?

Audio/Video Producer/Educator of JCreative Multimedia at www.jillcourtney.com

What subjects and grade levels have you taught? Any preference?

I have taught K-12 and college, and I think I prefer college, with middle school being a close second. High school would be third, and elementary fourth. I love all my students, though. I just relate to college and middle school students the most. Both college and middle school are defining periods in a student’s life.

What got you into teaching audio?

My first truly entrepreneurial adventure was a partnership called Sharkbait Studios, which originated in NYC. When my partner and I relocated the company to Nashville, we were networking among the local universities, of which there are many. During a networking meeting with the Chair of the Music and Performing Arts department at Tennessee State University, the Chair asked for my resume, and I happened to have it handy. Right then and there, he asked if I would teach TSU’s audio production classes, and he even utilized me as an applied voice instructor and the Director of the vocal jazz ensemble.

I was newly out of my Master’s program at New York University and had only taught music, voice, Spanish, and other K-12 topics. Once I taught at TSU for a year, I was in demand as an adjunct (ha!). I ended up working for Belmont University, The Art Institute of Tennessee-Nashville, and Nashville Film Institute, along with a 2-year out-of-state residency at Lamar State College-Port Arthur, where I taught Commercial Applied Voice, Songwriting, Piano, Music Theory, etc. Once back in Nashville, Sharkbait Studios was closed and JCreative Multimedia, my sole/soul venture was established.

What skills (both audio and life skills) do you focus on in your classroom?

I teach my students to listen to details in the music at hand, do their best in building the sound from the ground up, if that is their task, editing when the materials are flawed, and polishing a song into a finished product for online, CD or video applications. I teach them to keep the end goal in mind from the start, to plan too much, protect the quality of sound at every stage, and be a life-long learner without ego. Once you think you are a badass, you are finished. The most revered artists are the ones who are never good enough for their own standards and strive to be better than their former selves with every new project. I believe each new project should reflect an evolution of growth, and personally, I don’t believe in stagnating. So my skill set is constantly being added to or refined. A growth mindset is where it is at, and I hope that conveys amongst my students.

Equally important, I teach them that they must be prepared, punctual, professional, persistent and passionate about their work. If one of those elements slips, then the commitment won’t be present enough to find continued success over time, unless they luck upon a hit or a really fortunate employment scenario. I teach them to be twice as good and half as difficult as their competitors. In addition, I think it is important to paint a picture of reality for them on the job, because I would be doing my students a great disservice if I made it seem easy or glamorous because it takes a lot of years of hard work for the ease and glamour to show up, if ever it does.

I also teach my students the importance of beating deadlines. If a song or project is due on Tuesday, to have it done completely on Sunday to allow for tech glitches, tweaks or a buffer time for life to mess with you. Inevitably, life WILL mess with you, so having the peace of mind and a happy client is worth the extra effort. I love to under-promise and over-deliver with my clients. Often, the only pat on the back I get is a return client and a recommendation, and that is how I know I am doing well. This business isn’t for those who need verbal praise.

My students hear me preach about the importance of knowing the business side of the industry (music or film) as much as the technical/creative side. This is how you can be forever employable and indispensable to a company, team, or client.

What is generally your first lesson?

All lessons begin with the ear. Anyone who knows me will tell you that I am an excellent talker. However, it is my listening ability that keeps me working. Learning about the craft of sound in relation to spaces, the tools you utilize, and the subjects you wish to preserve through video and/or sound are crucial. But learning how to listen and reiterate what a client is seeking is perhaps equally crucial. If they come to you for a country track and leave with one that is a little too rock-like, they may love it, but will feel unheard or manipulated on some level. If the client makes those decisions along the way, that is one thing. But the client needs to steer that ship, and as professionals, it is our job to facilitate that vision and only inject our creativity or opinions if requested. There is such nuance in human communication, especially these days. Being a great listener and an effective communicator is arguably as important as having well-refined artistry.

What have you learned from teaching?

Teaching had refined my own skill set immensely. I wouldn’t know my craft as well if I didn’t have the pressure of being on top of my game so I don’t make a fool of myself in front of a room full of students. Especially in audio, being a minority, I have to know my subject well, or inevitably, it will become a reason why a student is disrespectful or discards my authority or knowledge. Teaching has also highlighted where my strengths and weaknesses exist. It has allotted me a second chance at fully learning the parts in which I was deficient, so I can parlay that effectively, and has given me practice and a platform for showing off my strengths, conveying my secrets to success with the true joy for teaching and helping others. It has given me as much as I have given to the world over the last 20 years of teaching. I have also connected with the next generations in a way that I never would have otherwise. I love kids and young adults, but I never wanted to be a mom. In this way, I get to leave a legacy in the minds of the masses, which better serves humanity, in my opinion,/circumstance.

Why is it important to include Arts (and STEM) in the general curriculum?

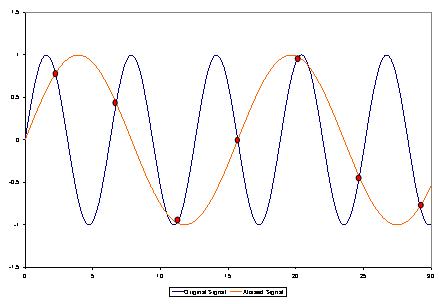

Funny you should ask this, as it is so very timely. My current research for my graduate Ed.S. program in Educational Leadership through Lipscomb University is focused on this very subject. The title of my research is “Promoting gender equity in audio and other STEM subjects.” I think that audio fields, specifically, are a perfect merge of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math, and with the new STEAM initiatives that are trending, the Arts portion is also covered. With STEM skills, it allows students to be versatile, and ultimately more successful in their future adult endeavors, which translates into more economic security, which translates into less hardship.

The more skills you have, the less you will starve. I am a walking advertisement for that fact, cause this body hasn’t missed a meal in 42 years. Ha!

What makes audio a unique subject to teach?

Audio/Sound is a trade or skill that at its root seems simplistic in nature. However, as you peel back the variables, the other factors around it become more vital. The space, the tools chosen, the subject, the mood, the health of the individual… there are so many variables that can distinguish one moment in time from another. And yet, it is also an art form. Some pay little attention to the process with a sole focus on the product, but audio must consider both as equally crucial. To further investigate, the business side, legalities, personal relationships, niche markets, and self-concept/limitations can all play into the final scope of one’s career in audio. It is unpredictable, beautiful and an immense challenge. It can be a dream come true or a total nightmare, and everything in between. Teaching this subject is as subjective as each individual in the class. It is constant differentiation.

Not everyone has an equally musical ear. Not everyone has gumption. Not everyone is healthy. Not everyone is intrinsically motivated. The best I can do is find out more about my students (by listening) and then cater to their strengths and enhance any identified weaknesses or lack of knowledge, provided that they are open to allowing me to do so.

I know you started a girl’s club in one of your schools, what was your goal in implementing it? How did your students respond? Do you have an interesting story from the group?

First, Nashville Audio Women Facebook group is an online place of connection for the few women who are studying and/or working in audio/sound in Nashville. The other was a girls’ club that I began at the middle school where I was teaching last year. My main mission for this club was girls’ empowerment because the middle school years are perhaps the most crucial for a growing girl in so many ways. Many of my students from that school, a Title 1 school, don’t have strong role models in their lives. Many had never met a woman like me.

Developing relationships based upon trust and respect was my primary goal. My secondary goal was to allow them to observe me as a strong female in this world, and once they knew me, they paid attention to how I interacted with the world. Another goal was to give them a person whom they could come to with all the questions they might have about being a female, kind of like an open-minded big sister. I think in this way, I was able to act as a role model that is unique – one that teaches because she digs helping kids, but also goes out and makes movies and recordings, sings with a rock band, pursues more academic degrees, and obsesses over animal photography in her non-teaching time. I wanted them to see that all of this is possible so that they might internalize it. My bottom line with my girls was to instill confidence and parlay life lessons. While they picked up on all of these things, they also wanted a space (in my classroom) where they could play touch football without boys. They wanted a place to paint their nails and video fake-fights for Snapchat. They wanted to ask me about boys and about periods and how to handle dramas with “haters.” I provided the space for all of that, as much as I could. I let the students direct how their club would go, largely, because I wanted them to build their own capacity as leaders and give them an honored voice.

How is mentorship important for young audio students?

I have many mentors. Many have been men, but I have found some incredible women too in more recent years. I believe they are crucial to growth and can help guide your career and provide you with a reality check and advice as you navigate the workplace. Mine are nothing short of lifesavers. For young audio students, I think one thing they don’t realize is that if all are successful, the audio instructor will eventually become a colleague, so the relationship they build with teachers is ever the more crucial. The teachers can help them find employment, write recommendation letters, and help them create lifelong connections. The reach of the teacher is often the potential reach of the student if the student proves her/himself to be worthy of such extensions of help and resources.

Any advice for the next generation?

Oh my, where do I begin? Well, I would highly suggest that any interested potential audio/sound student be as crystal clear as possible on the economic realities of this industry right now. I would encourage them to build an arsenal of skills that they can utilize in a variety of related industries. I would recommend focusing on the parts of the industry with the most jobs and welcoming atmospheres, and to be open-minded to all styles of music and sound jobs. I would also advise that they interview as many people as they possibly can along the way so that they can make informed decisions about how they want to paint their lives. Education has been key for me in remaining relevant and employed, both in the industry and beyond, and while I probably take it to an extreme that not everyone can handle, I recommend being a life-long learner. I am like a sponge with information, and am wholly unafraid to admit that I am uneducated in certain areas, but these are often the areas that arouse my curiosity. My former boss called me the ‘Swiss Army Knife’ of the department, which is flattering and probably a bit accurate. I want my students to be similar so that they can survive in their chosen industry for as long as it makes sense for them.

In addition, I always thought my career would be linear. We are always taught this as we grow up. But my career has taken the most unpredictable zigzags, and I have finally come to understand that in some cases, this is the norm. This business rarely sees someone graduate with a college degree, go into the field, stay at the same company and retire with a pension. So creative thinking, a diverse skill set and a willingness to change it up when necessary are crucial for forward motion