An Interview with Twi McCallum – The Woman Behind the Letter

On June 8, 2020, broadwayworld.com published Twi McCallum’s Open Letter to the Theatre Community on Hiring Black Designers and Creatives Twi McCallum Shares an Open Letter to the Theatre Community on Hiring Black Designers and Creatives. I came across this letter the following day, and I have to admit that I was quite struck by the letter’s tone. You really must read the entire letter for yourself, but I can tell you this: Twi gets right to the business of letting the entertainment industry know that hiring a Black cast does not mean your EDI box is checked. She writes that she’s, “tired of “inclusion” being exclusive to the actors, writers, producers, musicians, and dancers,” and that’s exactly the tone I’m talking about. She’s tired of it, and who wouldn’t be? The play does not stop at the stage. As everyone knows, that’s only the beginning, so why isn’t this inclusivity reaching backstage, to the shops, the design studios, etc.

I’ve seen this letter pop up in my social media feed several times since the first time I read it, and I’ve re-read it a few times. Each time I did, I couldn’t help but thinking, “I wonder who’s reading this and what they’re doing about it.” I reached out to Twi because I wanted to know more about her thoughts behind this letter, what made her write it, and what did she hope to accomplish with it, and I wanted to know what makes Twi tick. She graciously agreed to be interviewed, and here’s what she had to say:

You recently wrote an open letter to the theatre/arts/entertainment community on hiring black designers and creatives. Can you talk about your impulse for writing that letter?

The contents of the letter have been thoughts I’ve had drafted in my iPhone’s notepad for about 2 years, and sentiments I’ve felt since I was in undergrad (before I dropped out.) I attended Howard University, an HBCU, in their technical theater program. Although I was at a Black college, the school’s focus was to serve the acting students, so I was often told, “nobody cares about the designers and technicians” as if I shouldn’t use my artistry as an activism platform the way the performance majors were encouraged to. Here I was, about four years later, seeing a fantastic video from a Black Broadway actor going viral on social media, speaking out about racism he’s experienced. However, it was a little discouraging because Black actors are often given the platform to speak out. The thought of “representation” in entertainment is often limited to seeing Black actors, writers, directors, producers, musicians, and dancers getting big roles. Artists like me who work behind the scenes and are often nameless are seldom included in this “representation” picture. The letter is still evolving, I have several drafts of it and I plan to republish it next summer with a review of how I think the industry has progressed (or not) over a year.

Did you expect the letter to be so widely received? What was your reaction to that?

I still have no idea how “widely” my letter has been received, especially since I intentionally have not opened the links where it’s been published– I learned as a teenager not to read reviews and comments because some people intentionally say unkind things. BroadwayWorld posted on its Instagram page that they were opening their writing slots to Black people in light of the uprisings, so I saw that as my chance to write an open letter through the lens of a Black femme (and disabled) sound designer who works in theater as well as tv and film. I also submitted the letter to a few Black publications, who surprisingly did not publish my letter, which I assume is because they focus on highlighting actors and directors and don’t care about the Black artists who work behind the scenes. That rejection was a little discouraging until I started getting emails from veteran sound designers, former teachers, and regional theater companies that I worked for. I am still afraid of getting blackballed, but so far all of the responses from my network have been positive and encouraging. I’m sure that every minority designer can relate to my sentiments about physical abuse, sexual harassment, delayed payment, and wondering why a show with a Black cast/director has no Black designers. I chose not to name-drop particular companies where I experienced blatant racism, but I’m sure they all read it and wept.

What kind of responses have you gotten from industry folks?

Most of the responses from industry people have simply been to the effect of, “great job using your voice eloquently” and “you are a great role model.” I’ve also been invited to speak on a few panels since my letter was published, and my proudest result has been joining the EDI committee of Theatrical Sound Designers & Composers Association. Moving forward, I am trying to collaborate with the non-Black veteran designers to figure out ways to get more Black designers into job slots at regional and off-Broadway theaters in the upcoming seasons.

Who are your mentors, and why?

I have four mentors, who all have been warm and gentle towards me in different capacities. In no particular order: Nevin Steinberg, who has passed my resume along for at least 1 design job, and texts me every once in a blue moon to check-in, which goes a long way for me. Megumi Katayama, who took a chance and hired me as her design assistant at Long Wharf Theater in November 2019. I was grossly under qualified at the time but I was able to learn so much and being able to put that show on my resume opened doors for me. Mike Backhaus, the sound supervisor at Yale School of Drama, is a fantastic resource for all the engineering and mathematics-related sound things I haven’t mastered yet–he’s terrifyingly intelligent. Finally is Wingspace Theatrical Design, an advocacy organization for professional directors and designers based in NYC, and I’m being mentored by Sinan Zafar and Kate Marvin who have already helped me make important decisions in my career like unions, school, books to read, etc.

Can you describe the most comfortable and most equitable collaborative artistic situation for which you have been worked on?

My favorite production so far has been Frankenstein at Kansas City Rep in March 2020, we made it to opening night and then closed due to the virus. This is my first LORT stage as a sound designer, so I had big shoes to fill. This was not a “Black” production, both of the performers/writers were non-Black. The director was a non-Black woman, and I was the only Black designer on the team. When I saw the promotion for the show on the KC Rep website before arriving for tech, I was terrified because I had already convinced myself I was out of place. However, the organization didn’t make me feel like their token teammate. They trusted me, I got paid on time, it was a safe space to ask questions and expect a respectful response, my sound team picked me up when I fell short, and overall that level of comfort allowed me to produce my work to the best of my ability.

It’s a common discussion in this industry that once the “old guys” are gone, the upcoming younger generation will be able to enact real change for future generations. What is your response to this scenario? Do you think there is hope for meaningful change while the “old guys” are still here, or is it too late?

To an extent, I see many of the “old guys” helping to create real change for future generations. Of course, there are still racists popping into the conversations especially on social media, such as the situation with the Black producer who wanted to hire a Black film editor and got backlash from veteran White editors. At least in the sound design network, some of the old guys are showing up for EDI conversations and speaking up about the tangible actions they can take, such as making a commitment to bring on an emerging Black designer for one of their regional productions in a future season.

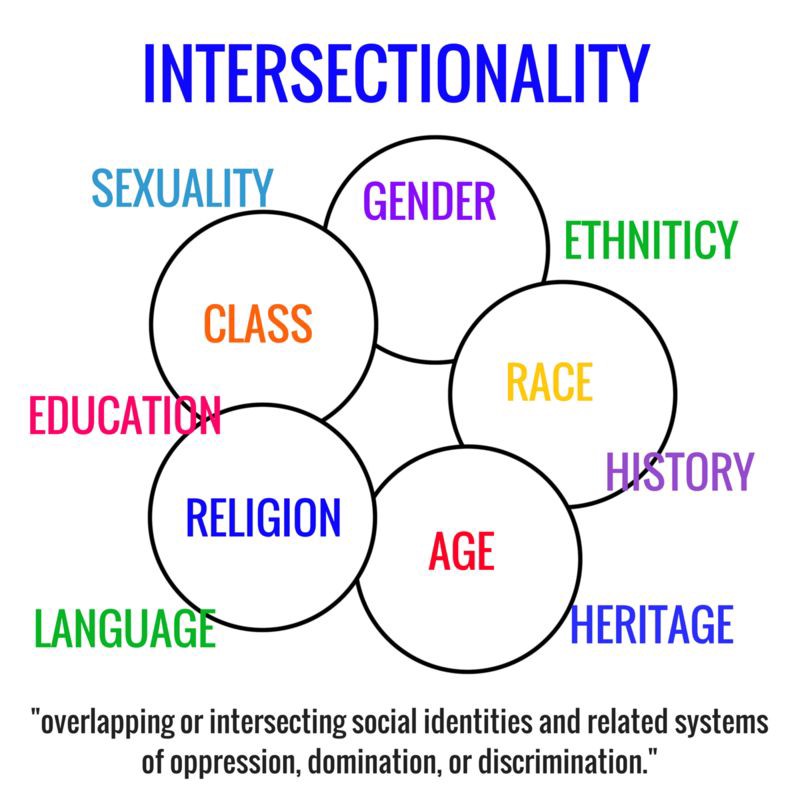

Job access is a multifaceted issue, including stems like pay disparity (because minorities are expected to work for free), education level, and access to expensive equipment if you’re a designer who comes from a low-income background. Institutionally, White-run theaters create barriers by hiring the same old guys consistently, and not having contact information listed on their website so that emerging designers can submit their resume to the producers/production managers, which creates a sense of exclusivity. Old guys making room is a good step towards getting more Black designers into these seats since many of them overbook themselves for productions that their design assistants are responsible for, but it’s not the only solution.

What is your dream project?

As a sound designer who works for the stage and the screen, this is a two-tiered answer. My dream project in theater: anything on Broadway! I already have my co-designer picked out for when I get hired for my first Broadway production, and yes she is a Black woman. I’ve had my eyes set on designing for a Broadway-bound director like Kamilah Forbes and Stevie Walker-Webb, along with a list of 30 other big directors I admire.

My dream project for cinema: post-sound mixing for many Beyonce films! She’s producing great content and I think she would love me as her post-sound girl.

However, the icing on the cake would be if I’m not the only Black, femme, and LGBTQ person on those technical teams. In a few years when I can grow as a businessperson, I want to have the power to train and recruit diverse engineers, A2s, foley artists, dialogue editors, etc who look like me.

Do you think that the pandemic outbreak has overshadowed the BLM movement and related initiatives that are being executed in the entertainment industry? If so, what do you think folx can do to stay focused?

I don’t think the pandemic outbreak has overshadowed the BLM movement, I think it’s the other way around. In regards to visibility, the problem is that non-Black counterparts participated in the temporary activism for about a week or two, then things went back to normal for them. Black people collectively are still mourning, marching, and organizing not only for George Floyd but also for Breonna Taylor, and new/rediscovered cases such as Elijah McClain, Oluwatoyin Salau, Sandra Bland, Tony McDade, and Riah Milton. Black women, trans people, and disabled people are often not cared for in these movements as much as Black men are. I want everyone if they have the capacity, to show up as much as they can, sign petitions, and donate to grassroots organizations instead of large nonprofits that aren’t proving where the funds are being allocated. BLM is an ongoing movement, even when the fire settles down.

What advice do you have for young technicians, designers, crew, and any other “unsung heroes?”

Advice on your job hunt: Send out your resume as much as possible! Cast your net wide. Last year, I sent my resume to about 80 theaters and directors I wanted to work for and only heard back from 6, but those responses turned into jobs.

Advice on creativity: practice, practice, practice. Practice your QLab, ProTools and other industry-related software, sign up for free webinars, join lots of industry organizations, watch YouTube tutorials, etc.

Advice on being comfortable in your own skin: My favorite quote is by a man named Michael Todd, “…planted and under-qualified” which means we may not always have enough experience or readiness for a job, but still take the opportunity when it comes and do your best.

Resources for hiring a diverse production crew

Wingspace is committed to the cause of equity in the field. There are significant barriers to accessing a career in theatrical design and we see inequalities of race, socioeconomic status, gender identity, sexual orientation and disability across the field.

Parity Productions is a formidable producer of new work, that also ensures that they fill at least 50% of the creative roles on their productions with women and trans and gender nonconforming (TGNC) artists. In addition to producing their own work, they actively promote other theatre companies that follow their 50% hiring standard. Artistically, they develop and produce compelling new plays that give voice to individuals who rebel against their marginalized place in society.

Production on Deck Uplifting underrepresented communities in the arts. Their main goal is to curate a set of resources to help amplify the visibility of (primarily) People of Color in the arts.

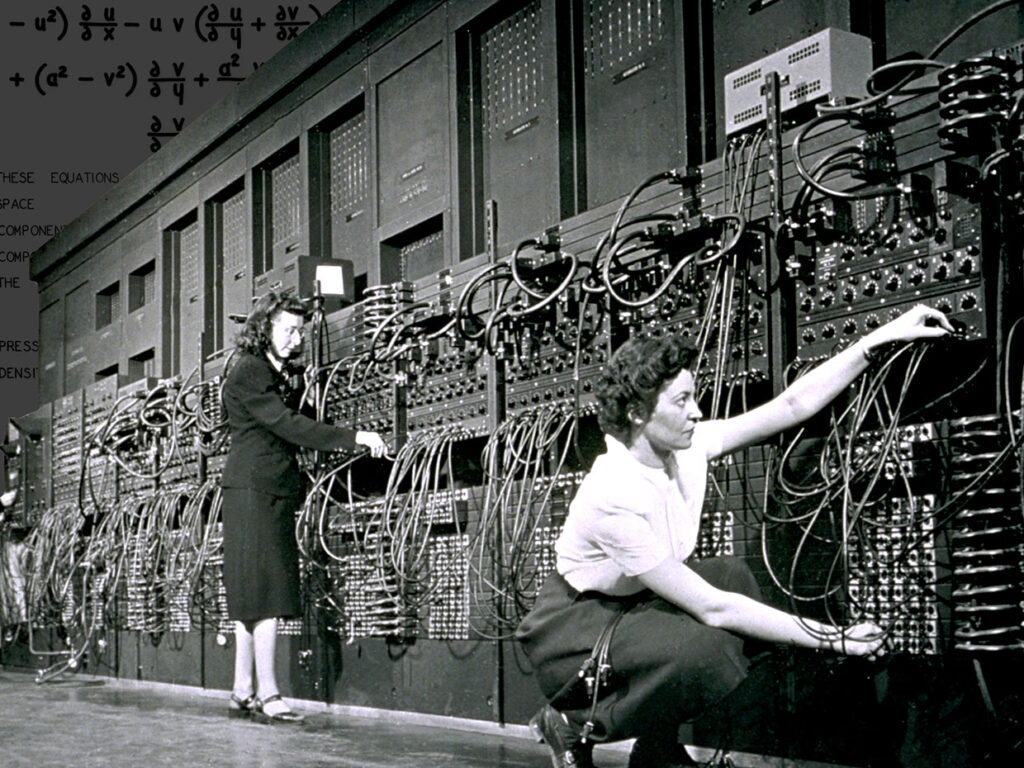

POC in Audio Directory The directory features over 500 people of color who work in audio around the world. You’ll find editors, hosts, writers, producers, sound designers, engineers, project managers, musicians, reporters, and content strategists with varied experience from within the industry and in related fields.

The EQUAL Directory is a global database of professionals that seeks to amplify the careers and achievements of women working behind the scenes in music and audio. Any person around the world can add their name and claim their space. And, any person looking to hire a more inclusive creative team can find professionals in their area.

Twi McCallum is an NYC-based sound designer for the stage and screen. Her first jobs in the big city were a technical theater apprenticeship at New York Live Arts and an IATSE Local 1 stagehand gig at Manhattan School of Music.

Off-Broadway credits include Women’s Project Theater. Selected television/film credits include ABC, HBO, Warner Bros, CBS, and NBCUniversal. Selected regional credits include Kansas City Rep, Cape May Stage, and Long Wharf Theater (assistant design.) Twi has also designed Parity Production’s spring 2020 production of “Mirrors” at the New York Theater Workshop.

Selected Awards/memberships include USITT Early Career Mentee Grant, Post New York Alliance, SoundGirls, and Disney Creative Careers Fellow.