Beth O’Leary is a freelance monitor engineer and PA tech based in the U.K. She has been working in the industry for 11 years and is currently working as a stage and PA tech on the Whitney Houston Hologram Tour. She has toured as a system tech with Arcade Fire, J Cole, the Piano Guys, Paul Weller, a tour featuring Roy Orbison as a hologram. She recently filled in as the monitor engineer for Kylie Minogue and just finished a short run for an AV company in Dubai.

Beth O’Leary is a freelance monitor engineer and PA tech based in the U.K. She has been working in the industry for 11 years and is currently working as a stage and PA tech on the Whitney Houston Hologram Tour. She has toured as a system tech with Arcade Fire, J Cole, the Piano Guys, Paul Weller, a tour featuring Roy Orbison as a hologram. She recently filled in as the monitor engineer for Kylie Minogue and just finished a short run for an AV company in Dubai.

Live Sound was not her first career choice, as Beth was originally attending university for zoology. Although she has always been passionate about music. She remembers the first festival she attended “I remember the first festival I went to (Ozzfest 2002 – the only time they came to Ireland), and the subs moving all the air in my lungs with every kick drum beat. I thought that was such a cool thing to be able to control. When I heard about the student crew in Sheffield it made sense to join.: Join she did and it was there she learned “ everything about sound, lights, lasers, and pyro in exchange for working for free and letting my studies suffer because I was having too much fun with them.”

Her studies did not suffer too much as she graduated with a Masters’s in Zoology, but she would go on to work as a stagehand at local venues, eventually taking sound roles at those venues as well as a couple of audio hire companies. Even though she had no formal training, she would attend as many product training courses for sound and few focused on studio works. She says at the time “real-life experience was more important than exam results when I started, I think it’s changing a bit now. But, it’s still essential to supplement your studies with getting out there and getting your hands dirty.”

By her mid-twenties, she wanted to expand her skills and start working for bigger audio companies. After a lot of silence or “join the queue” replies to her emails asking for work experience from various companies, she met some of the people at SSE at a trade show. She would learn that they are really busy over the festival season and said she was welcome to come to gain experience interning in the warehouse. She remembers arranging to intern for three weeks “I put myself up in a hostel and did some long days putting cables away and generally helping out. A week in, they offered me a place as stage tech on some festivals. I’m pretty sure it’s because one of their regulars had just broken his leg and they needed someone fast! I then spent most summers doing festivals for SSE. After a few years I progressed to doing some touring for them. I now also freelance for Capital Sound (which became part of the SSE group soon after I started working with them!) and Eclipse Staging Services in Dubai, amongst others.”

Can you share with us a gig or show or tour you are proud of?

Can you share with us a gig or show or tour you are proud of?

I baked a cake on a moving tour bus once, I’m very proud of that…

Apart from that, I used to run radio mics for an awards show for a major corporate client. Each presenter was only on stage for a couple of minutes, but the production manager didn’t like the look of lectern mics or handhelds, so everyone had to wear headsets. Of course, we didn’t have the budget or RF spectrum space to give everyone a mic that they could wear all night, we needed to reuse each one three or four times. I put a lot of work into assessing the script and assigning mics in a way that would minimise changes and give the most time between changes. I then ran around all night, sometimes only getting the mics fitted with seconds to go. I always made sure to take the time to talk to the presenters through what I was doing (and warned them about my cold hands!) and make sure they were comfortable. I did the same show for about five years and was proud that the clients, most of whom were the top executives for a very large corporation, were always happy to see me, and asked where I was by name when I couldn’t make it. Knowing that the clients appreciate you is a great feeling.

Can you share a gig that you failed out, and what you learned from it:

I was doing FoH on a different corporate job, the first (and last) gig for a new company. I had terrible ringing and feedback on the lav mics. It was one of those rooms where it will still ring, even if you take that frequency out wherever you can. I worked on it all through the rehearsal day, staying late and coming in early on the show day, trying to fix it. I did most of the ringing out while the client wasn’t in the room, so as not to disturb them. I asked the other engineers in other rooms for advice, and probably followed my in-house guy’s lead a bit too much. I figured he knew the room the best of anyone, but in hindsight, he wasn’t great. The show happened, and the client was smiling and pleasant, but it definitely could have been better.

Afterward, I got an email from the company saying the client had complained to them about my attitude. I was devastated. I had worked as hard as I could, and I pride myself on always being as polite as possible! I realised too late that from the client’s point of view, they saw an issue that didn’t get fixed for a long time, and they didn’t see most of the work I put in or know what was going on. I learned that it is so important to take a couple of minutes to keep your client in the loop and let them know you’re doing your best to fix the issue, without going overboard with excuses. It can be hard to prioritise when you’re so focused on troubleshooting and you don’t have much time. I still have to work on it sometimes, but it can mean the difference between keeping and losing a gig.

What do you like best about touring?

The sense of achievement when you get into a good flow. So few people realise how much work is involved. For arena shows, we arrive in the morning to a completely empty room, we bring absolutely everything except the seats. We build a show, hopefully, give the audience a great time, then put it all back in trucks and do it all again the next day.

What do you like least?

When the show doesn’t go as well as it could. There’s no second take if something goes wrong that’s it and you can’t go back and change it. It’s quite difficult not to dwell on it. All you can do is make sure it’s better next time.

What is your favorite day off activity?

I love exploring the cities we’re in. My perfect day off would be a relaxed brunch with good coffee, then a walk around a botanical garden, a bath and an early night. Rock and roll!

What are your long-term goals?

I need variety, so I’d like to stay busy while mixing it up. Touring and festivals, music and corporate shows working with different artists and techs. I’d also like to get to a position where I can recommend promising people more and help them up the ladder.

What if any obstacles or barriers have you faced?

I think one of the major barriers in the industry is people denying any barriers exist. I was told I needed a thicker skin, to toughen up, everyone has it rough. Then after years of keeping my head down and working hard, I saw how my male colleagues reacted to words or behaviour that didn’t even register as unusual to me anymore. Their indignation at what I saw all the time really underscored how differently they get treated.

Thankfully I have done plenty of jobs with no sexism at all, but it can be frustrating to get told I don’t understand my own life. Just because you don’t see what you consider to be discrimination, doesn’t mean it never happens. It can be particularly disappointing when young women are outspoken about how sexism isn’t a problem, ignoring the groundwork set by the tough women who came before them.

I have also struggled a lot with a lack of self-confidence, which can really put you at a disadvantage when you’re a freelancer. You need to be able to sell yourself and reassure your client they’re in safe hands, so I’m sure the self-deprecation that comes naturally to me has held me back.

How have you dealt with them?

I try to give people the benefit of the doubt as much as possible. Whether I misunderstood their intentions or they’re honestly mistaken, or they genuinely don’t want to work with a woman, all I can do is remain professional and courteous and do my job to the best of my ability. A lot of the time we get past it and have a good gig, and if we don’t I know I did all I could. I take people’s denial of sexism as a good sign, in a way. It shows it is becoming less pervasive and I hope the young women who are so adamant it doesn’t happen are never proven wrong.

I’m still working on my self-confidence. I try to remember that the client needs to trust me to relax and have a good gig themselves. I aim to keep a realistic assessment of my skill level. I used to turn jobs down if I wasn’t 100% sure I knew everything about every bit of equipment, for the good of the gig. I then realised that a lot of the time the client wouldn’t find someone better, they’d just find someone more cocksure who was happy to give it a go. Now I’m experienced enough to know whether I can take a job on and make it work even if it means learning some new skills, or whether I should leave it to someone more suitable.

The advice you have for other women and young women who wish to enter the field?

Be specific when looking for help. If you want to tour, please don’t ask people “to go on tour”. Pick a specialism, work at it, get really good, then you might go on tour doing that job. When I see posts online looking for “opportunities in sound”, I ignore them. What area? Live music? Theatre? Studio? Film? Game audio? What country, even? Saying “I don’t mind” will make people switch off. People looking to tour when they don’t even know which department they want to work in makes me think they just want a paid holiday hanging out with a band.

Most jobs in this field are given by word of mouth and personal recommendations. Networking is an essential skill, but it doesn’t have to mean being fake and obsequious. The best way to network is to be genuinely happy to see your colleagues, and interested in them as people. And always remember you’re only as good as your last gig. You never know where each one will lead, so make the effort every time.

People who run hire companies are incredibly busy, and constantly dealing with disorganised clients and/or very disorganised themselves. Don’t be disheartened if they don’t reply when you contact them. Keep trying, or get a friend who already knows them to introduce you so you stand out from the dozens of CVs they get sent every week. Make it easy for employers. You are not a project they want to work on. Training takes time and money. They don’t want to know you’re inexperienced but eager to learn. Show them how you can already do the basic jobs, and have the right attitude to progress on your own.

Must have skills?

Number one is a good work ethic. You can learn everything else as you go along, but if you aren’t motivated to constantly pester employers until they give you a chance, turn up, work hard and help the other techs, all the academic knowledge in the world won’t help you.

Being easy to get on with is also essential. We can spend 24 hours a day with our colleagues, often on little sleep, working to tight schedules and people can get grumpy. Someone who can remember all the Dante IP addresses by heart but is arrogant and rude won’t go as far as someone who can admit they don’t know things, but is willing to ask questions or just Google it, then laugh at themselves later.

Staying calm under pressure, communicating clearly and being able to think logically are all needed for troubleshooting.

Anyone who tells you that having a musical ear is determined at birth is just patting themselves on the back. Listen to music, practise picking certain instruments out and think about how it’s put together. Critical listening can be learned and improved, even if you have to work at it more than some others.

Favorite gear?

Gadget wise, I love my dbBox2. It’s a signal generator and headphone amp in one and produces analog, AES and midi signals so it helps with so many troubleshooting situations and saves so much time.

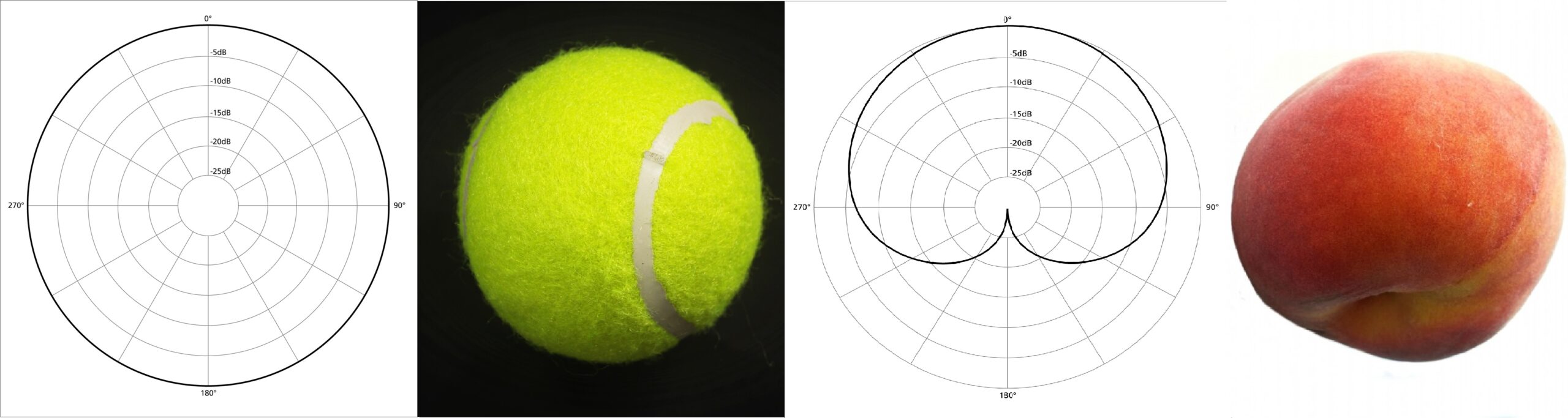

I use my RF Explorer a lot to get a better idea of the RF throughout a venue and can use it to track down problem areas or equipment.

As far as desks go, I don’t have loyalty to a particular brand. They all have their advantages. I still have a soft spot for the Soundcraft Vi6 because that’s what I used in house for years. DiGiCo seems pretty intuitive to me and has a lot of convenient features. I spent most of the last year using an SSL L500. It sounds fantastic and has a lot of cool stuff to explore.

Parting Words

It can take a long time to break into this industry. I had been doing sound for nine years before I went on a tour, and then didn’t do much touring again for a couple of years after that. You have to be tenacious and patient. However, if you find yourself in a situation where you aren’t progressing, or the work environment is toxic, leave. As a freelancer, you shouldn’t rely too heavily on one client anyway. And that’s what they are: clients. When a friend pointed out these people aren’t your bosses, they’re your clients, it really helped me to change my approach. I now rely less on them for support, but I’m also free to prioritise favoured clients over others. Live sound can be rough around the edges, but there’s a difference between joking around and bullying. There’s a difference between paying your dues and stagnating. If you’ve been in a few negative crews it can be easy to believe that everywhere is like that, but it isn’t. Keep looking for the good ones, because they do exist.

Laura Clapp Davidson heads up the retail market development team for Shure. She brings passion and knowledge of gear that comes from over 15 years in the MI industry. When she isn’t talking about music equipment, she’s singing or playing through it as a professional singer/songwriter. Laura lives in her hometown of Guilford, CT with her two daughters, two dogs, two rabbits, and one very patient husband.

Laura Clapp Davidson heads up the retail market development team for Shure. She brings passion and knowledge of gear that comes from over 15 years in the MI industry. When she isn’t talking about music equipment, she’s singing or playing through it as a professional singer/songwriter. Laura lives in her hometown of Guilford, CT with her two daughters, two dogs, two rabbits, and one very patient husband. Fela is a graduate of Full Sail University with 20 years of experience in audio engineering and inducted into the University’s Hall of Fame in 2020. Her mixing experience at front of the house position includes Ron Carter, Brian Blade, Jose Feliciano, Meshell Ndegeocello, Bilal, and almost a decade with 6-time Grammy Award winner Christian McBride, mixing sold-out shows across Asia, Europe, Canada, and America.

Fela is a graduate of Full Sail University with 20 years of experience in audio engineering and inducted into the University’s Hall of Fame in 2020. Her mixing experience at front of the house position includes Ron Carter, Brian Blade, Jose Feliciano, Meshell Ndegeocello, Bilal, and almost a decade with 6-time Grammy Award winner Christian McBride, mixing sold-out shows across Asia, Europe, Canada, and America. Larry Milburn, Producer: Award-winning filmmaker Larry Milburn has been involved as a producer/editor on several behind-the-scenes EPK’s and DVD documentary projects for both film and commercial production studios as well as advertising agencies such as FOX, Columbia Pictures, BBDO Detroit, RSA, and BMW.

Larry Milburn, Producer: Award-winning filmmaker Larry Milburn has been involved as a producer/editor on several behind-the-scenes EPK’s and DVD documentary projects for both film and commercial production studios as well as advertising agencies such as FOX, Columbia Pictures, BBDO Detroit, RSA, and BMW. Beckie Campbell is a FOH, Mon Engineer, and Owner of B4Media Production. As a twenty-year veteran of the music business, Beckie has had the honor to help mentor and train teams for several theaters, live events, and houses of worship. All while touring as a FOH Engineer for major acts and still working local hometown gigs. Beckie has had the pleasure to work with major acts such as Indigo Girls, Altman Betts Band, The Commodores, Nicole Nordaman, Firehouse, Colt Ford, Ace Freely, Julian Marley, Gary Pucket and Union Gap, just to name a few. She has also mixed at the New Orleans Jazz Festival, 30A Songwriters Festival, and does the live and on-air mixes for the City of Orlando Christmas Tree and 4th of July Live Shows. Early in her career, she was a Technical Director/FOH Engineer for two Mega Churches in Florida.

Beckie Campbell is a FOH, Mon Engineer, and Owner of B4Media Production. As a twenty-year veteran of the music business, Beckie has had the honor to help mentor and train teams for several theaters, live events, and houses of worship. All while touring as a FOH Engineer for major acts and still working local hometown gigs. Beckie has had the pleasure to work with major acts such as Indigo Girls, Altman Betts Band, The Commodores, Nicole Nordaman, Firehouse, Colt Ford, Ace Freely, Julian Marley, Gary Pucket and Union Gap, just to name a few. She has also mixed at the New Orleans Jazz Festival, 30A Songwriters Festival, and does the live and on-air mixes for the City of Orlando Christmas Tree and 4th of July Live Shows. Early in her career, she was a Technical Director/FOH Engineer for two Mega Churches in Florida. Chris Leonard has been in the professional live audio world for almost two decades, following in the footsteps of his father. As a monitor engineer with Maryland Sound International, he toured with artists like Tears for Fears, Don Henley, Disturbed,

Chris Leonard has been in the professional live audio world for almost two decades, following in the footsteps of his father. As a monitor engineer with Maryland Sound International, he toured with artists like Tears for Fears, Don Henley, Disturbed,