Excellence in Assistance

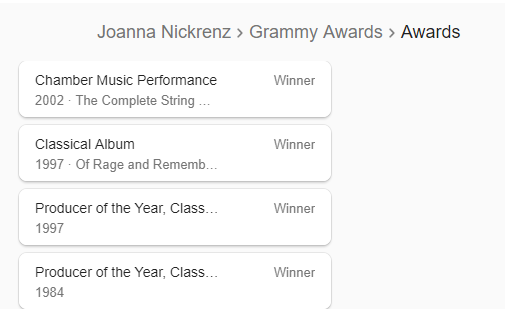

Learning how to be a great assistant is one of the best ways to put yourself on the path to mastery in commercial music production. As important as it is to know the technical and creative aspects of your craft, it’s equally important to understand how social and interpersonal dynamics function in the studio environment. Knowing how to operate equipment might get you in the room, but knowing how to deal with a multitude of needs, problems, and personalities will keep you there. No one cares whether or not you’ve got a degree in engineering if you don’t know basic, real-world studio etiquette.

Every studio and every recording session comes with its own culture. Make it a point to understand the culture of every session you’re involved. Being able to read the room is an invaluable skill. It imparts competency, attention to detail, pride in your work, and investment in your team.

Some sessions will be clear and to the point. There will likely be a professional team in place. Your job here is to help things run smoothly and make sure that everyone has what they need. In situations like this, you’ll defer directly to the lead engineer and probably won’t interact too much with the clients. This is the kind of session where you want to be “invisible”—wear basic clothing, try not to speak unless spoken to (with exception to polite greetings and the like), keep a low profile. Stay out of the way, but be hyper-present and ready to jump in when you’re needed to change out a mic or take a food order. If you become aware of a technical issue that no one else seems to notice, find an expedient but non-disruptive way to make the issue known to your lead engineer. Be prepared to take action on a moment’s notice.

Whether you’re working in a large, commercial facility or a small project studio, hospitality should be a top priority. Keep coffee hot and fresh. Have a kettle ready to fire up when a singer needs tea. Make sure artists’ riders have been satisfied to the best of your ability. Keep beverages, pens, paper, and other basic items plentifully stocked. Personally, I try to bring extra items with me just in case. Candy, aux cables, guitar accessories, adapters, phone chargers, tampons, and other such items can be a great door opener. For example, I had the chance to get friendly with super producer Don Was during a session because I was the only one in the building who had dental floss. The better you can anticipate and facilitate the needs of others, the more of an asset you will be in any production.

Of course, there will be sessions that test the limits of your patience and professionalism. The producer may be inexperienced or unable to communicate effectively. They may get angry or throw you under the bus when they make a mistake or are not able to properly manage a session. They may have an ego issue and feel the need to assert dominance to feel like they’re in control. This may be a genuine personality trait, or it may be what they think they need to do to impress or intimidate their clients (yes, this is an actual production tactic and you’d be surprised at how often it works). They may be dealing with a difficult artist and funneling that frustration your way because they have to remain in service of their client. Perhaps the artists themselves are inexperienced, egotistical, or unprofessional, and the whole room is suffering for it. There may be substance abuse or behavior that isn’t necessarily conducive to productivity. It’s your job to be prepared to navigate these challenges with patience, composure, and effectiveness. Stay solutions-minded and try to keep your feelings and judgments in check. If things escalate to the point of being abusive or dangerous, extract yourself from the situation and speak to a supervisor.

Some sessions will be relaxed, and you’ll become friendly with the artists and/or producer. In my experience, most artists prefer the kind of environment where they feel a sense of ease and camaraderie with the crew. The level of friendliness will depend on your ability to read the room and to adjust your personal levels accordingly.

Making a record can be an intensely bonding process. If you’re being invited to be a part of the bonding, you should participate! You just might forge relationships that will last throughout—or even advance your career! However, don’t lose sight of how important it is to stay professional while you’re on session. Studio etiquette should always be your default setting when you’re on the clock, and the artists/producers should be handled with a clear sense of priority and deference.

Additionally, understand that your friendly relationship with clients might not extend past the sessions themselves. Sometimes the spirited nature of relaxed, friendly sessions is just what the artist needs to get through their process. Don’t take it personally if a producer asks for your card but never calls, or if an artist talks about wanting to hear what you’ve worked on but doesn’t offer a clear opportunity for you to present it, or if you don’t get a follow back on Instagram, or whatever. Keep a sense of confidence and equanimity around you and stay centered on what’s most important—providing excellent service and doing what it takes to make a production successful.