The Creative Process of Illumination

The importance of light is not only to appreciate the stage or the viewer to see the artist, whether an actor, musician, dancer, etc. Lighting is a complement to the show as important as any other. With light, we can create an entire concept, a unique atmosphere for each show depending on the type of event.

Now, how can this be achieved? It is definitely not an easy task!

First of all, we must bear in mind that to be an illuminator it is necessary to have knowledge of the equipment, color theory, voltages, among others, we must also have a lot of practice since lighting is a profession like any other.

Second, there are some specific factors that we need to consider before we start; Let’s start by identifying the type of show we are going to light, it could be dance, opera, a concert or television, depending on the type of show it we can determine how we are going to enlighten. Once we identify it, we have to know the overall concept of the work, for example, if our artist has a more theatrical concept such as Castañeda, Tricycle Circus Band, Lady Gaga, Michael Jackson, to name a few. Working with these types of artists is complicated since they have a very peculiar way of visualizing their show (the music, the theatrical concept, the drama of the show) and the way they seek to communicate with their audience is complex. I do not mean that other artists do not have their complications, but these examples are useful because the idea of a concert exceeds what we usually see in a show, this makes it unique and unforgettable for each of its spectators.

Now, since we have the concept; the next step is to know the tastes of our artist (favorite colors, if you like strobes, etc.). This step is essential to start designing, and we can do it without the need of a very sophisticated equipment or software. Simply by having a great imagination, blank paper, and some colors you´ll have more than enough, although the above makes the work considerably easier.

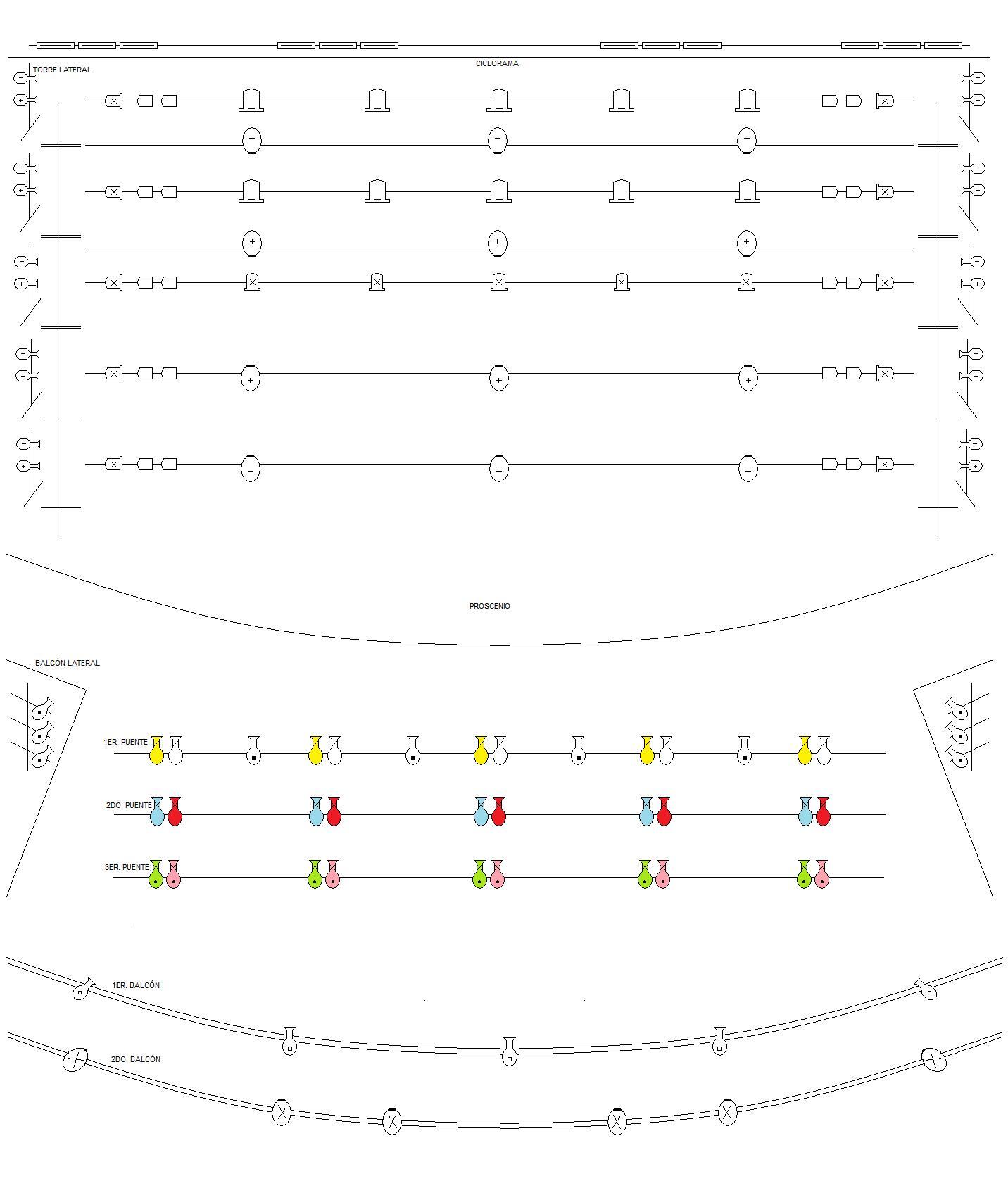

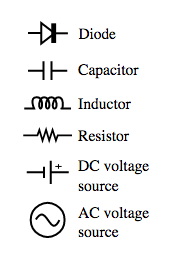

To design, you must first realize your light plot or plane of lights. This is the basis of all your design since in it you place the equipment you are going to use and the location according to the characteristics of the place where the show will be presented. In it you must specify the type of luminaires you need, if they are conventional, LED, mobile, etc., how many you need, the voltage they use, the watts of power you require and if necessary the filters, gelatins or Lucas (whatever you call them) and even the console you want to use.

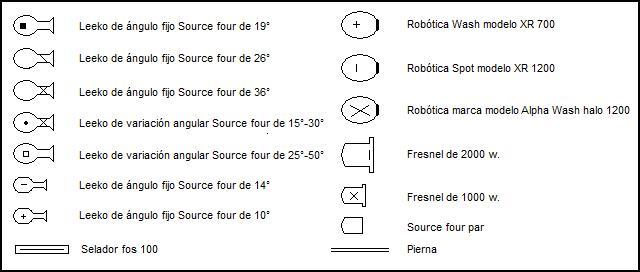

Once you have your light plot, then you start designing your cues or render. This can be done from a downloaded software either free or paid, there are many in the market, some of the best I have tested are Titan de avolites, MA of GrandMA and Magic Q of ChamSys, which are also free; but as I said, it is not mandatory that you use them, you could also use a sheet of paper and colors. The important thing is that when you get to the venue you have a clear idea of what you want to achieve.

The advantage of designing/using software is that you can arrive with a programmed show and optimize the time on the console to correct the positions of the lights you will use at important moments, to highlight an action or the artist himself. Although in the entertainment world not everyone has the opportunity to always have the console we want, there will come a time when we can ask to have a fixed rider, although for that you´ll need a lot of experience and patience.

In the case of the theater, we depend on the console that the venue has, for example, in the Lebanese theater where I work, there is an ETC Element. Soon will arrive an ETC ION XE, but in the City Theater Esperanza Iris there is a roadhog console and Avolites Pearl Expert (both Venues located in the CDMX), which is why it is more complicated to schedule a show, but once you have your render, you can arrive at the venue to program your show without any problem.

Finally, a good design of lights does not depend on the equipment that is counted, but on the creativity and imagination that each illuminator has. In addition to the constant preparation and practice, the trial and error that each of the operators can have makes your performance grows.

Mary J. Varher – Dancer, choreographer, teacher and illuminator. She started her career as a dancer in Guadalajara at age 14 and at 15 as an actress, that’s where she had her first approach to enlightenment. Later she moved to the CDMX where she studied the degree in classical dance teaching at the National School of Classical and Contemporary Dance, where she also receives scenic production classes from Jana Lara, thus having her second approach to enlightenment and being fascinated so it could be achieved with an unlikely element. She did her social service at the Raúl Flores Canelo Theater under the tutelage of Ivonne Flores. As their needs increased, they continued to learn from great teachers such as Carlos Mendoza, Zanoni Blanco and Mario Flores. She has worked on various projects such as “Sound-body-image connection” under the direction of Antonio Isaac, in dance companies “Project Bara” “Spatio Ac Tempore” and “Mexico Espectacular”, among others, she has participated as an engineer of lighting with artists such as: Genocides of the Mystery and Descartes a Kant. She is currently working as head of lighting at the Lebanese Theater in the Lebanese center located at the CDMX.

Mary J. Varher – Dancer, choreographer, teacher and illuminator. She started her career as a dancer in Guadalajara at age 14 and at 15 as an actress, that’s where she had her first approach to enlightenment. Later she moved to the CDMX where she studied the degree in classical dance teaching at the National School of Classical and Contemporary Dance, where she also receives scenic production classes from Jana Lara, thus having her second approach to enlightenment and being fascinated so it could be achieved with an unlikely element. She did her social service at the Raúl Flores Canelo Theater under the tutelage of Ivonne Flores. As their needs increased, they continued to learn from great teachers such as Carlos Mendoza, Zanoni Blanco and Mario Flores. She has worked on various projects such as “Sound-body-image connection” under the direction of Antonio Isaac, in dance companies “Project Bara” “Spatio Ac Tempore” and “Mexico Espectacular”, among others, she has participated as an engineer of lighting with artists such as: Genocides of the Mystery and Descartes a Kant. She is currently working as head of lighting at the Lebanese Theater in the Lebanese center located at the CDMX.