Paradoxes In Vocal Editing

I tend to procrastinate recording vocals for my original songs because I get so worked up about recording my voice perfectly. I worry about making sure my recordings are high quality: I’ve minimized outside noise, gain staged properly, warmed up my voice, am conveying emotion and proper pitch, and have enough takes to work with. Keeping track of all this can be so overwhelming that most of the time when I feel ready to record, I just want to do one take and be done with it. So many singers before the age of digital recording were performing single takes, so why can’t I? Of course, if I’m not careful with my recording takes, I end up spending more time in iZotope RX and Melodyne cleaning up noise, mouth clicks, and pitch anyways. Since a lot of my music is electro-pop-based, the vocal editing needs to be clean so that it fits the production and the genre.

I can’t help but feel like a minimal amount of vocal editing gets us closer to authentic performance, and yet we have all these new technological tools that we can use to produce a perfect Pop vocal. In diving into the philosophy of vocal editing instead of actually doing it, I rediscovered a short clip of Billie Eilish demonstrating vocal comping to David Letterman, which you can view here if you haven’t seen it yet. She and Finneas O’Connell walk through editing of the lead vocal for her song “Happier Than Ever” and point out how almost each word is a separate take. They don’t use autotune and instead take extra time during the recording process to make sure every syllable in every phrase is perfect in pitch and tone and time. They do this seamlessly so that upon playback you really can’t tell that these takes are separate. Most producers do this, and the O’Connells did not invent this technique, yet I’m mostly impressed by the sheer resilience it takes to record the same word or syllable over and over again without completely losing your mind.

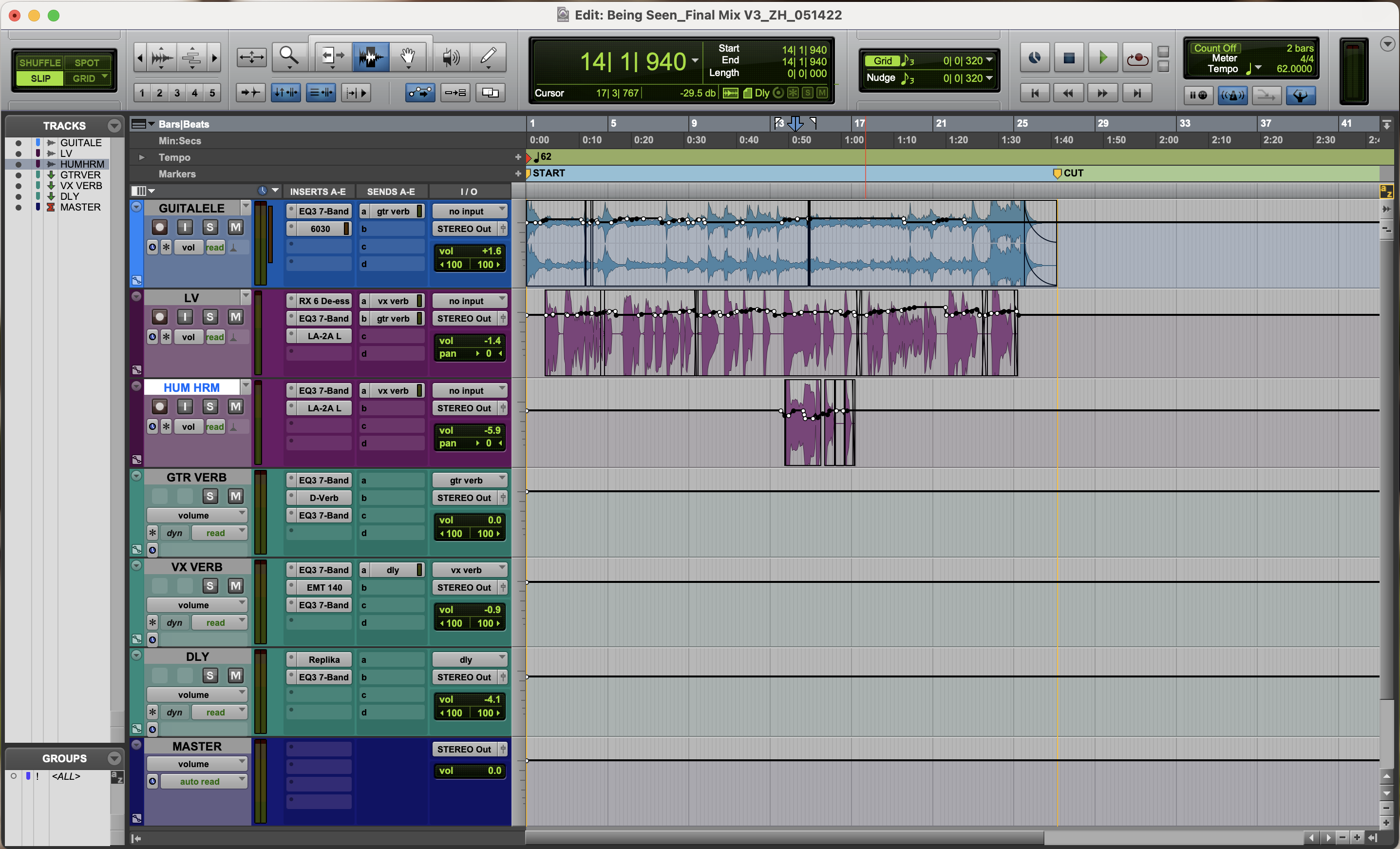

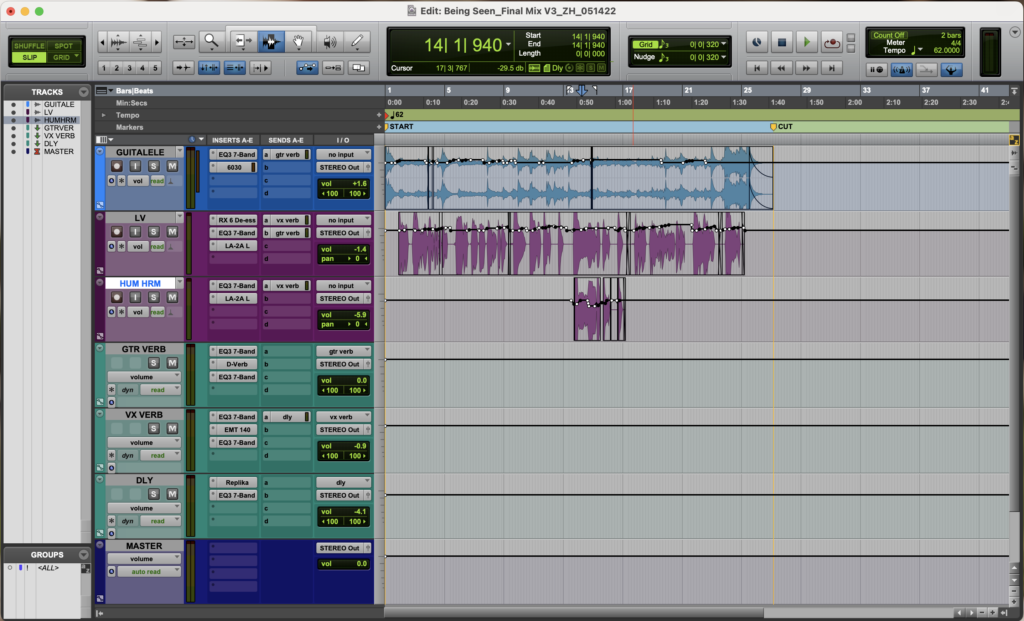

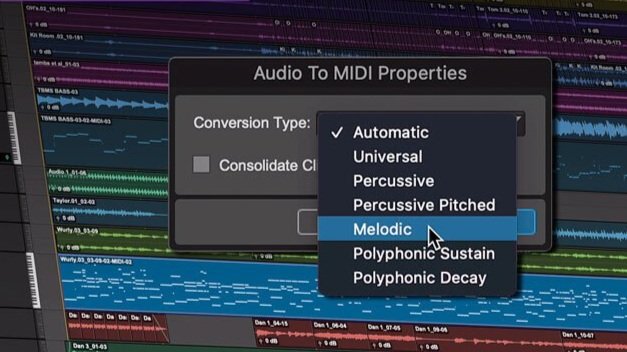

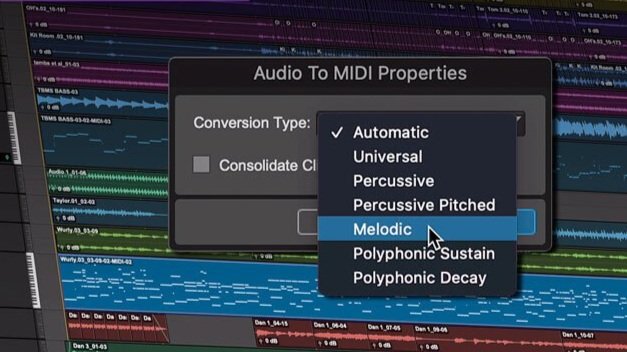

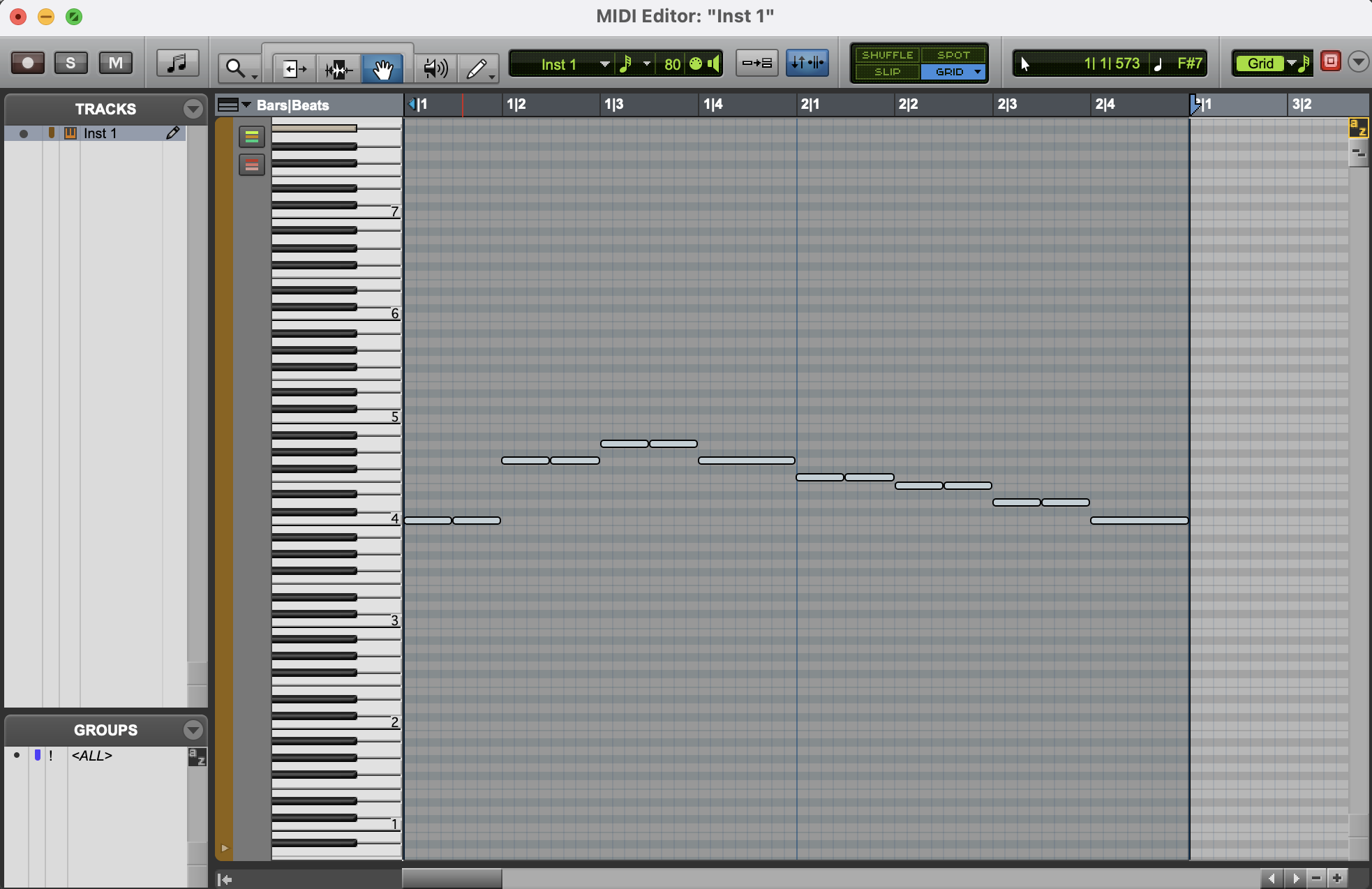

Another video I found, which you can view here, shows Charlie Puth recording, comping, and editing his vocals very meticulously. He splits up the recording of a two-syllable phrase just so he can use pitch shifting to sing the higher note of the phrase at an easier pitch for him. To be clear, instead of recording himself singing an octave up, he uses SoundToys Little Alter Boy to pitch his voice down and sing a lower note, which he then pitches back up to the right key so it sounds like his tone is fuller when he sings higher. He also punches each note in over and over until he gets the result he wants instead of playlisting and comping later, and he manually lines up harmony takes in Pro Tools instead of using Vocalign. He really uses the DAW itself as the editing tool instead of other plug-ins, and his philosophy is that since we are privileged to have this technology, it’s worth taking the time to make a quality edit.

I yearn to master these techniques confidently and efficiently. As someone who gets overwhelmed easily, I usually record until I get a take I like instead of playlisting. I also realize that quickly comping multiple takes in the moment of the recording process is super valuable despite it resulting in the derealization of my own voice. More than anything, I want my voice to sound like my voice, which usually takes a lot less thinking and tinkering and a lot more feeling and emotion. Still, as a low-budget indie artist wearing almost all the hats, how can I decide if perfecting the performance is a better use of my energy than mastering comping and editing techniques? I admire you if you have the energy to do it all.

I’m always reminded of how Stevie Wonder records. For Songs In the Key of Life, nothing was spliced, and takes were rerecorded instead until they were right. This seems frustrating, but Wonder’s elite musicianship made this a viable process. Four years before this record was out, “Superstition” was recorded with a world of mistakes. This is one of my favorite recordings because it’s radically authentic. The squeak of the kick pedal lingers throughout the track, and if you listen closely you can hear the brass players discussing their parts since they didn’t get time to practice.

So, I might be a little biased towards how I define an authentic recording based on how accurately it conveys emotion and how close it feels to a one-shot live performance, which is a little old-school. However, when I record and edit my own vocals, I usually end up using one or two takes. I clear out the mouth clicks with RX, I tune the important notes in Melodyne, and I try to think about it as little as possible. I know that a little extra elbow grease in each step of the process might give me a perfect result, but I completely disconnect from the point of recording when I start on that journey. I tend to view authenticity and perfection as opposites, but learning about how other producers approach this work shows me that authenticity and perfection thrive on reciprocity. I don’t know if there’s a right way to edit vocals, but I know that no one can tell you the right way to do it.