Part 2: The sound operators – behind the scenes with Ella Wahlström and Helen Skiera

Last month, I reviewed Complicite’s The Encounter from a sound design perspective. This month, I wanted to get an insider’s view from the sound operators, Helen Skiera, and Ella Wahlström.

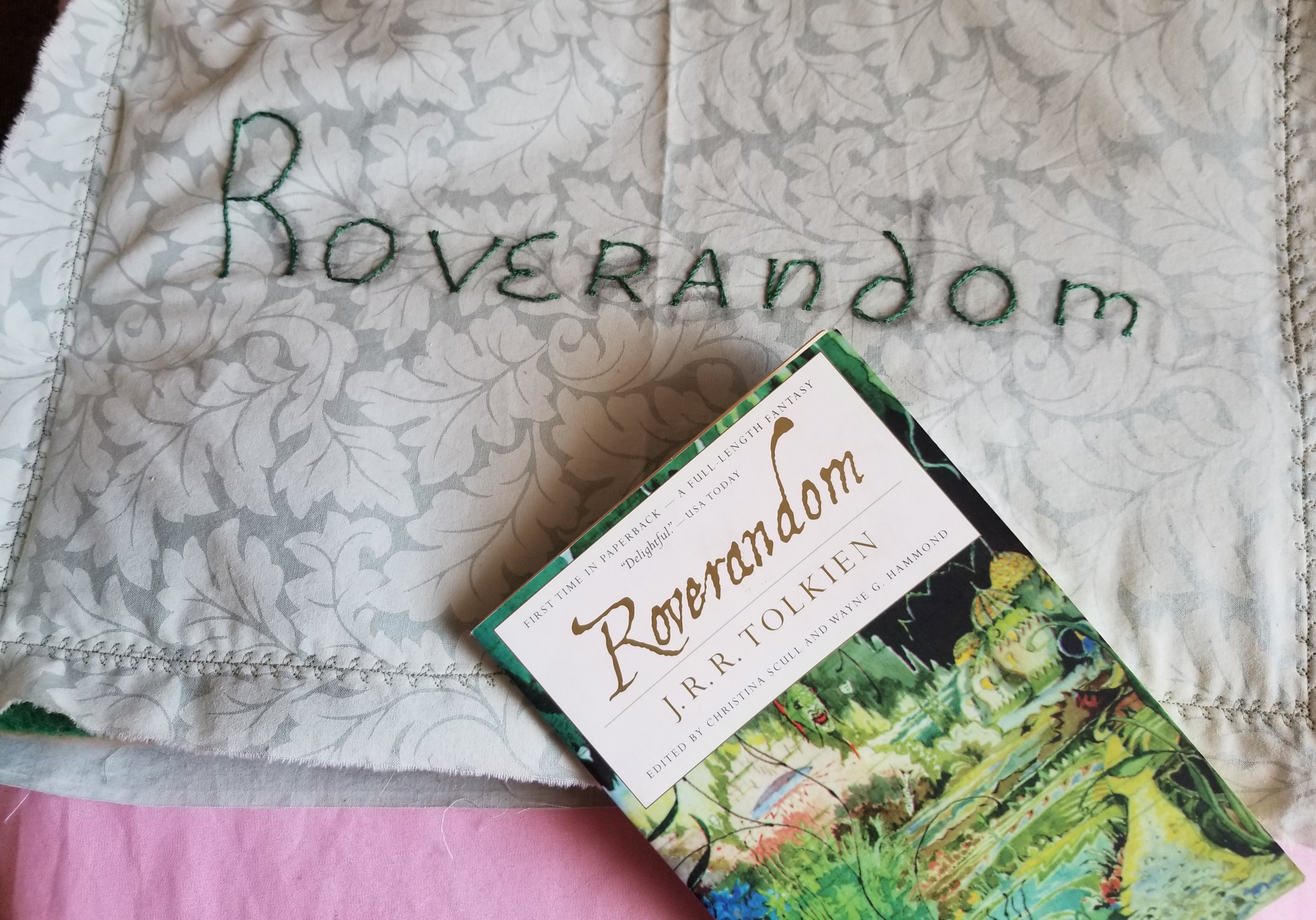

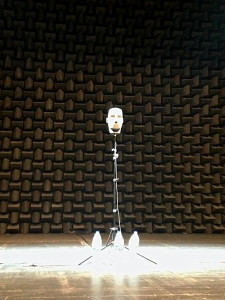

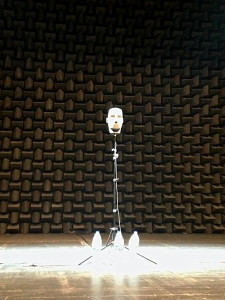

A quick recap for context: The Encounter is a one-actor show directed and performed by Simon McBurney, with sound design by Gareth Fry with Pete Malkin. It incorporates binaural technology, voiceovers, live looping, and sound effects to transport us into different environments as diverse as the Amazon and Simon’s living room. The audience experiences the sound through headphones worn throughout the two-hour performance.

A quick recap for context: The Encounter is a one-actor show directed and performed by Simon McBurney, with sound design by Gareth Fry with Pete Malkin. It incorporates binaural technology, voiceovers, live looping, and sound effects to transport us into different environments as diverse as the Amazon and Simon’s living room. The audience experiences the sound through headphones worn throughout the two-hour performance.

I’ve heard The Encounter described as a play for “one actor and two sound operators”, and I feel this sums up the important role of the sound design in the show. I think any audio person who has watched the play will recognise the astounding feat of achieving that level of accuracy, clarity, and subtlety night after night. So how does the magic happen? Over to you, Ella and Helen.

You’re both sound designers as well as operators. Can you tell me a bit more about your respective backgrounds in sound?

Ella: I’ve studied violin since I was a child and had been part of my school’s tech team when I discovered theatre sound design as a teenager. It suddenly seemed to combine all my areas of interest and skills. For a couple of years, I did various amateur and semi-professional sound gigs in Finland before I decided to move to London in 2010, and here I completed a Bachelor of Arts in Performance Sound at Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance. Over the past six years, I’ve gradually built up my portfolio as a Theatre Sound Designer in London.

Helen: I started as a musician, and I took an interest in technology to record the bands I was in, and actually, my GCSE music pieces – that was back in the days of small Tascam Portastudios. Using various home/school recording setups, I started to understand how a desk worked, and with that knowledge I ended up, while at university, working with the Dundee Rep Community Theatre, making music and setting up PA systems for shows. I also started to get work as a live sound engineer for bands when I lived in Edinburgh. It wasn’t until much later that I discovered sound design was an actual role in theatre. When I did, I wanted to learn from the beginning, so I observed designers whose work I enjoyed, and work experience, and every low/unpaid fringe show that I could take on. I was very fortunate to be taken on as an operator at the Royal Court Theatre and spent about two years working on some incredible shows. These included one of Gareth Fry’s – Sucker Punch, which was the first time I’d seen Ableton and a Launchpad, which was very influential for me.

How did you become involved with The Encounter?

Ella: I had worked for Gareth Fry as an associate sound designer before, and I’ve also done a couple of Complicite research & development workshops as a sound operator and designer. So I guess I was a safe choice to be asked to come on board.

Helen: Gareth was looking for someone to do something in rehearsals for two weeks. I had no idea what it was, but I was free, and I’ll take any opportunity to work with Gareth. That was September 2014, and I’m writing this from Athens where we are currently performing the show, and, amongst other projects, I’ve been working on this ever since then.

The Encounter requires two sound operators, which is unusual for theatre production, and in particular for a solo show. What are your different responsibilities on the show?

Ella: I operate the music and sound effects side of things. I have a Mac Mini and a YAMAHA QL1, I run QLab and Ableton Live on the Mac, using a go-button, two Beringer BCF2000 controllers with eight faders each, and a launch pad. We’ve programmed the big sequences in QLab, and we use Ableton to run a lot of continuous tracks, like music, atmos and drones. The QLab cues trigger and reset Ableton tracks so that I can ride the volume levels on the BCF faders according to the performance. On the launch pad I have spot effects and some backup tracks on Ableton, this allows me to fire tracks out of the QLab sequence.

Whenever there are any changes made to the show, which there are quite often, I’m responsible for reprogramming and implementing new recordings into the show. I do a daily rig check, which includes checking all my operating equipment, the PA, onstage speakers, the show iPod, and my MIDI connection to lighting and video. Luckily our sound supervisor has the responsibility of checking all the headphones daily with the in-house crew. I often run Midi Monitor to gather logs of the show, so after every show, I save these logs and the current QLab file.

Helen: I operate the microphones and a system of devices that loop Simon’s voice and assist him to loop himself. I have a Yamaha QL1 desk, two Mac Minis (one for backup) running Ableton Live (for looping and some vocal effects), and two Qlab files, with no audio, but MIDI commands to enable all the control surfaces, desk and software to communicate. There’s one BCF fader bank, one Bob (custom-made button box), one launchpad, and one icon fader bank. For my preshow checks, I check that everything works: all mics, all pitches, vocal effects, looping from my controls, and looping from the controls on stage. There’s no written check-in program, so it’s probably less formal than the average show checks.

What backups do you have in place?

Ella: Pretty much everything that can go wrong has gone wrong at some point during the show or rehearsals, so there are a lot of backup solutions implemented. I’m running a backup computer, which tracks the main computer so if anything happens to the main computer I can just swap over and change to a backup patch on my desk to continue the show on the backup. Within the show system, on my launchpad, I also have backups of all the tracks played on stage through the iPod and also all the main atmos, drones, and music tracks, so if anything happens to QLab, or on stage, I can bring in a track to cover or mask. On my desk, I also have the option to route the onstage speaker’s feed straight to the audience headphones in case there’s anything wrong with the wireless speaker or the radio receiver on it.

Helen: I have a second Mac with the same software, but if other units were to fail, we would have to revive them or continue without them. Because there isn’t a series of linear events that has to happen the same way each night in the same order, there are generally more options of how to do the same task, so there have been occasions when I’ve had to be a bit creative with problem-solving mid-show.

Yes, I imagine that operating sound for a show as aurally complex as The Encounter has both challenging, and rewarding, aspects.

Ella: The most challenging aspect of operating the show is definitely the ever-changing performance. It’s a one-man show and Simon treats us as fellow performers and likes to keep the show alive by trying new things and changing things around a bit. He knows our restrictions quite well but ever so often pushes the boundaries and keeps us on our toes. It’s also just over two hours long and full of sound, I think my longest break between sound cues is about two minutes. So operating takes a lot of concentration, and you really need to get into the story and the performance to keep up and stay within the rhythm. But when it all works together and I create a good flow with the voice-over dialogues I have with Simon, and I can feel his next move on stage, it’s a magical show, and it’s very rewarding to be part of the experience we create for the audience.

Ella: The most challenging aspect of operating the show is definitely the ever-changing performance. It’s a one-man show and Simon treats us as fellow performers and likes to keep the show alive by trying new things and changing things around a bit. He knows our restrictions quite well but ever so often pushes the boundaries and keeps us on our toes. It’s also just over two hours long and full of sound, I think my longest break between sound cues is about two minutes. So operating takes a lot of concentration, and you really need to get into the story and the performance to keep up and stay within the rhythm. But when it all works together and I create a good flow with the voice-over dialogues I have with Simon, and I can feel his next move on stage, it’s a magical show, and it’s very rewarding to be part of the experience we create for the audience.

Helen: The challenging parts are kind of similar to the rewarding parts – it takes a lot of concentration and focus, and this is continuous throughout rehearsals as well as performances. We’re so actively part of it all the time. During rehearsals and performances, we create the material as it happens; it’s not the same as when you just replay the creative elements that you made earlier. So it can be exhausting, and very daunting at times, but this is also what makes the show such a brilliant experience for an operator.

In what other ways is operating The Encounter different from operating sound for other, more traditionally produced, plays?

Ella: In more traditional theatre productions, the operator aims to deliver the same show night after night, and the sound designer should be able to come in at any time during the run and find the show pretty much as they left it on press night. On The Encounter we’re adapting the show all the time, I save a new QLab file every other night after having reprogrammed something.

Helen: For a traditionally produced play, in my experience, design is aiming to create the same experience for every audience every night, with fixed levels and cue points that cannot be changed, and would not be changed by an operator anyway. With The Encounter, it is more like being armed with a series of tools, or instruments, ever-developing, and the show starts, and you do whatever you think/feel should be done. Yes, the main structure of the show has a rehearsed form and what I do is within that form, but potentially, something different can happen at any moment. I do have to look at the stage, and particularly Simon, pretty much for the entire two hours. I can glance down to operate the loopers, but looking away for more than a second usually means I miss something.

I imagine that having to work at that level of responsiveness might require you to create bespoke hardware solutions?

Helen: We initially mixed the show conventionally, but found it was getting more and more difficult to do the changes quickly. Taking other mics down as well as bringing up a fader, and doing that with one hand while using the other to loop wasn’t efficient enough. Gareth’s solution was to create “Bob”, which is a box with 12 buttons that each send a MIDI message (like a Qlab GO box). The MIDI messages go into Qlab, and Qlab sends control changes to the QL1, to bring up individual microphones and pitches, and take the others down instantaneously. We are currently on Bob Mark 2; the original Bob had the buttons arranged in a single line, which meant I needed to look at the buttons to get the right ones. For Bob 2, I designed a pattern for the buttons arranged in threes, which means I can feel around the surface without having to look down.

As well as multiple mics, Simon uses various devices to create and playback sound on stage, including a wireless domestic hi-fi speaker and an iPod. I remember Ella saying the wireless speaker requires you to trigger occasional bursts of noise to prevent it from switching off. Are there any other little quirks that you have to be aware of during the show?

Ella: The iPod is another risk-averse element as it’s on stage and out of our reach, so whenever Simon plays anything from it, I have to be ready to play a backup track, in case he turns the volume down accidentally or something else unexpected happens.

Speaking of unexpected sounds, using live looping must run the risk of inadvertently involving the audience when they cough or make other sounds. I’ve heard the story about when a school group came in and made a lot of noise which was picked up by the binaural head, and the group thought it was hilarious when they could hear it played back as part of a loop. How do you cope with unexpected ambient sounds?

Helen: I do have backups, but they are definitely a last resort. Usually, I grab the loop; then if there is a cough, I delete it and grab another one. It’s a risky game, though, as each time you discard a loop, the source sound may stop being made, and then there’s not much you can do. But Simon is very adept at noting when there is coughing, and he will keep making the sound for a bit longer to allow for a clean loop.

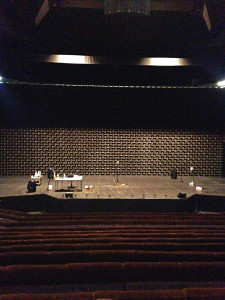

How does the show change from a sound perspective when you take it on tour – what do you need to take into account when you’re in a different venue?

Ella: We install the headphone system in each venue, which means our sound supervisor has to plan all the cable runs and amp placements every time as the venues vary in shapes and sizes. You would also think that a show that you only hear through headphones wouldn’t be too dependent on the acoustics of the room, but the acoustics affect the clarity of the sound quite a lot. Also, the noise level of an auditorium is crucial to the flow of the show as the binaural head is used throughout. If the space has noisy air-conditioning, for example, it can be problematic when swapping between the close-up microphones and the binaural head. When you create layers by looping the binaural recordings the noise floor rises with each layer.

Many thanks to Helen and Ella for this interview. There’s more about the making of The Encounter here and for upcoming tour dates go here and scroll down under “Tour”.