Readings and Workshops and Labs, oh my!

In a previous blog which you can read here, I detailed some of the key differences between mixing an existing work (or revival) and mixing a new musical. New musicals, as many of us know, are their own special beast, always evolving and keeping you on your toes as you process changes in real-time. But getting to the premiere production is already a long way down the road, and before that, a show will go through various iterations and phases. Often those phases won’t have a full production design with sets, costumes, etc. Perhaps they won’t be more than some actors with binders and one musician at a keyboard. There will, however, almost certainly be a sound designer and a mixer. In this blog, we will be diving into the specific challenges of mixing presentations of shows that are in development: what they are, why we do them, and how to set yourself up for success as the mixer.

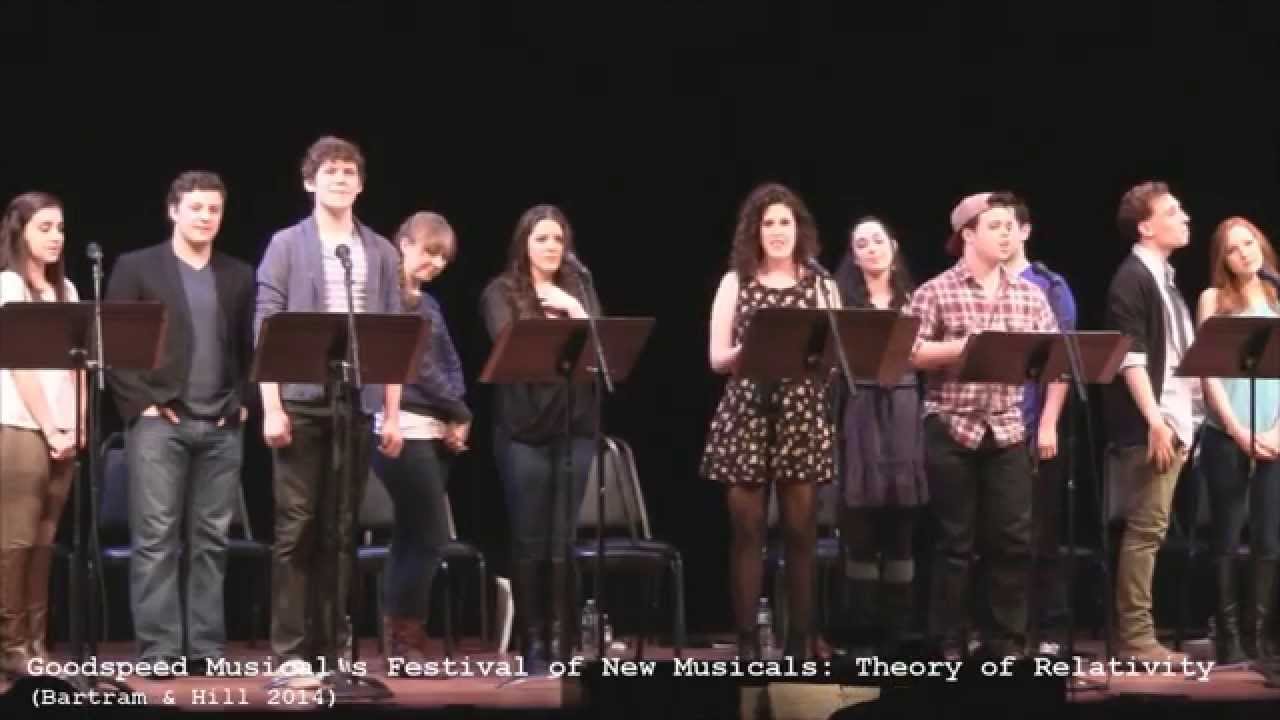

A still from a staged reading of the musical “Theory of Relativity” produced as part of Goodspeed Musicals’ annual Festival of New Musicals.

What are the different ways to present a work in progress?

The three most common terms for a public presentation of a show in development are readings, workshops, and labs. First, some quick definitions are in order.

Reading: A presentation of a musical where the show is read and sung aloud for an audience by a group of actors. As its name would suggest, reading is almost always done with scripts in hand, i.e. the actors are not “off book.” Sometimes readings are more of the “concert” variety, with actors at music stands delivering their lines; sometimes they include more staging and choreography (hence the term “staged reading”). Since most readings are not considered to be fully staged, someone will often be tasked with reading some of the stage directions aloud to give the audience a sense of what’s going on in the play. The actors will not usually be in wireless mics and the sound support will consist of some handheld mics set up near music stands, or at other strategic locations around the stage. Other times the actors will be in wireless mics for ease of mixing and moving around. The orchestration will typically be minimal (e.g., a keyboard and possibly a rhythm section).

Workshop/Lab: A workshop is a fully-staged presentation of a show where the actors have memorized their lines and are performing the show “full out,” complete with choreography. Technically, as of 2019, a workshop of a show is a “lab,” but we’ll get to that in a moment. There might be a few minimal props, or a large-scale approximation of the set, much like you might see in a rehearsal room for a full production of a show. There aren’t usually costumes and there is not a lighting design other than “lights up, lights down.” The actors will be in wireless mics, and the expectation is that the presentation will be mixed line-by-line, like a standard musical. There is almost always a band, and likely a larger audio support package including either foldback wedges or a personal monitor mixing system like Avioms.

Fun fact: The history of the workshop dates to the 1970s, when a director/choreographer named Michael Bennett gathered a bunch of Broadway dancers in a room for a few weeks to try out writing songs and scenes based on some cassette tape interviews he had done with them about their lives working as what we in the biz call “ensemblists.” The result was the musical “A Chorus Line” which went on to run for over 6000 performances on Broadway.

Today, the words “lab” and “workshop” are often used interchangeably to describe a developmental process where a show is “put on its feet” and “presented” to either the public or an invite-only audience.

Side note about the word “lab”: Remember a few paragraphs ago when I said that all workshops are technically labs? “Lab” is now the technical word used to describe all developmental presentations or work sessions governed by the Actors Equity Association, the labor union representing theatre performers and stage managers in the US. The new lab contract has multiple tiers that delineate how much staging or props can be used, how many weeks of work can be done, and how much the actors and stage managers are paid per week. Additionally, as was the case in the former workshop contract, actors and stage managers who participate in a lab of a show that goes on to turn a profit on Broadway are now entitled to a small cut of the box office gross (https://broadwaynews.com/2019/02/08/actors-equity-reaches-agreement-on-lab-contract-ends-strike/). This is to account for the fact that even though they may not have been the directors, writers, or choreographers themselves (and might not even be working on the show if/when it gets to Broadway), the work and contributions they made back in those labs are an integral creative component of the eventual full production and should be recognized and compensated. The lab is meant to be overall more flexible as to how the producers and directors are allowed to use the time that they have their actors on payroll.

Why do shows do these developmental steps?

Two big reasons: to experiment and make changes to a piece before investing lots of time and money into a full production, and to “pitch” your show to potential producers and investors who might be willing to get behind a full production of the work if they think it has potential. It’s basically a place to work out your show’s kinks before putting on a “backers audition.” The team is here to “sell” folks on their idea for this musical. As the mixer, you are there to help them make their case by delivering the dialogue and music as clearly as you can so that they can decide if the songs are catchy, the jokes are funny, the story is meaningful, etc. This means that your goal behind the faders will be a little different than just “making it sound good.”

So without further ado, let’s get into some tips and tricks for how to do this!

DON’T. GET. FANCY.

This is probably the single biggest and most overarching piece of advice I can give when mixing developmental work. This process is going to feel like mixing a new musical on OVERDRIVE. The changes will be flying at you even more quickly, and you want to be able to adapt and react quickly and efficiently.

So, what are some ways you can do that?

DON’T GET FANCY with your programming.

Write as few snapshots/scenes as you possibly can. Do the least amount of programming you and your designer can get away with. Unless there is a compelling reason to do more (e.g., it’s what your designer wants), your programming really shouldn’t be anything more than some VCA changes, a little bit of band mixing/fader wiggling, and maybe a little bit of reverb safing/unsafing.

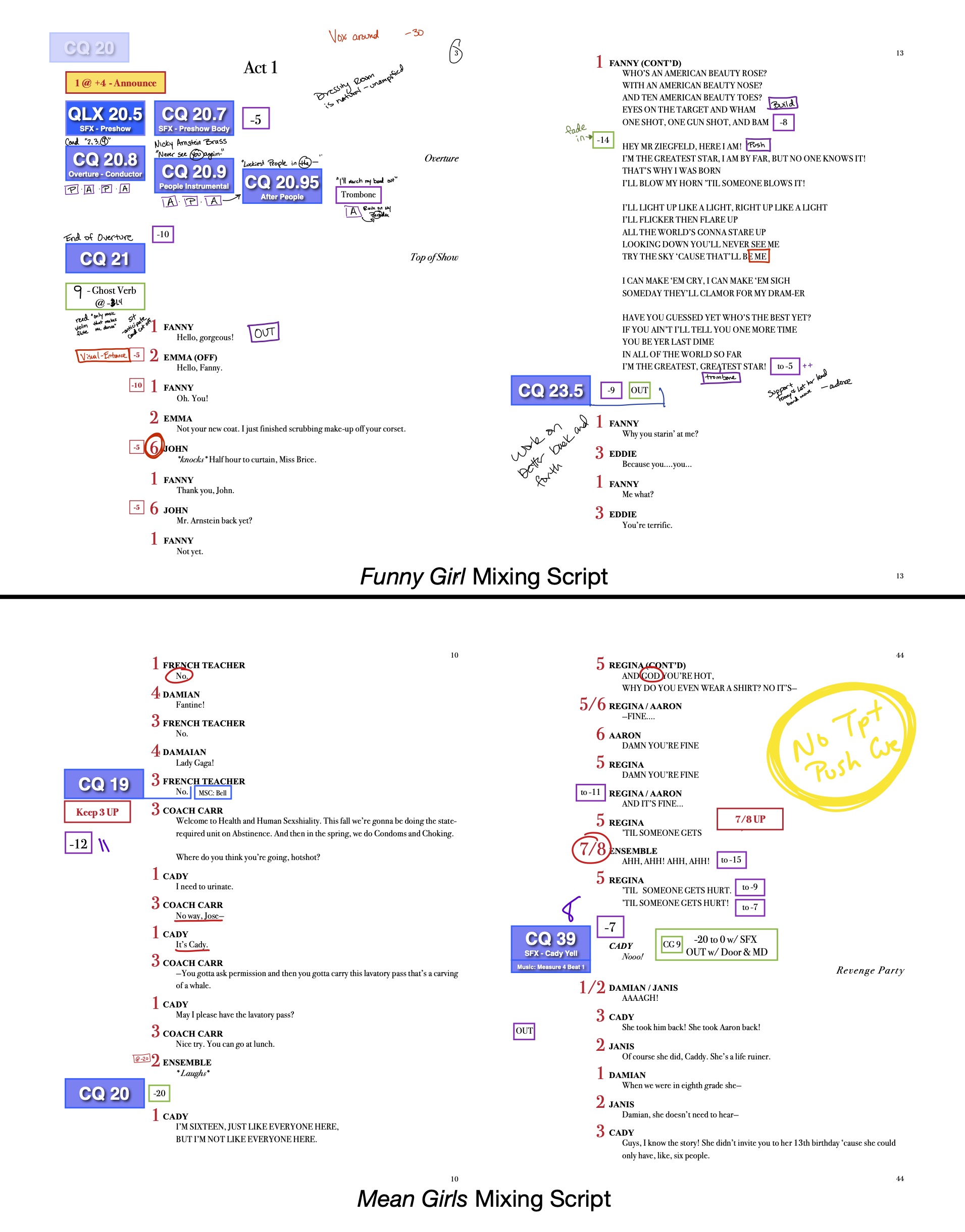

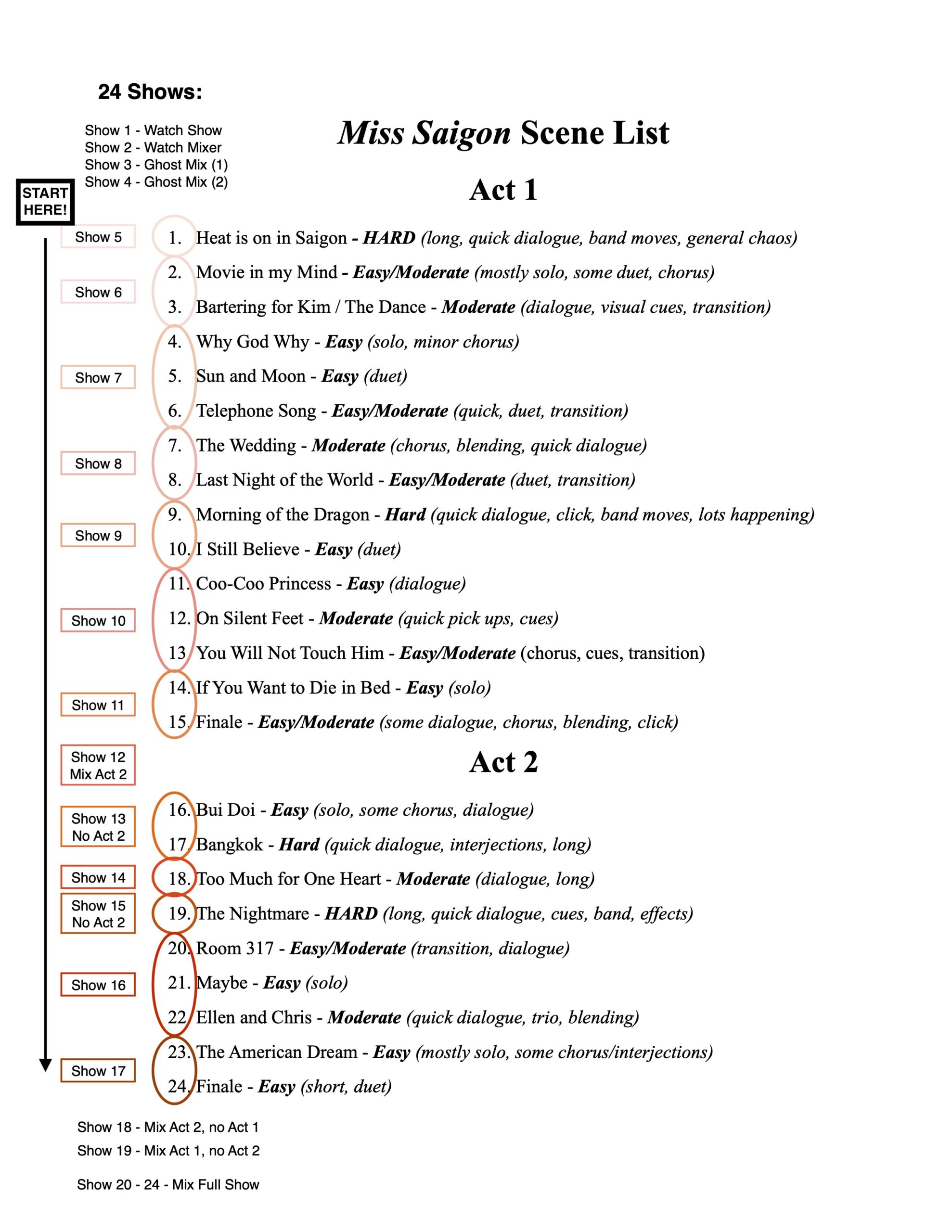

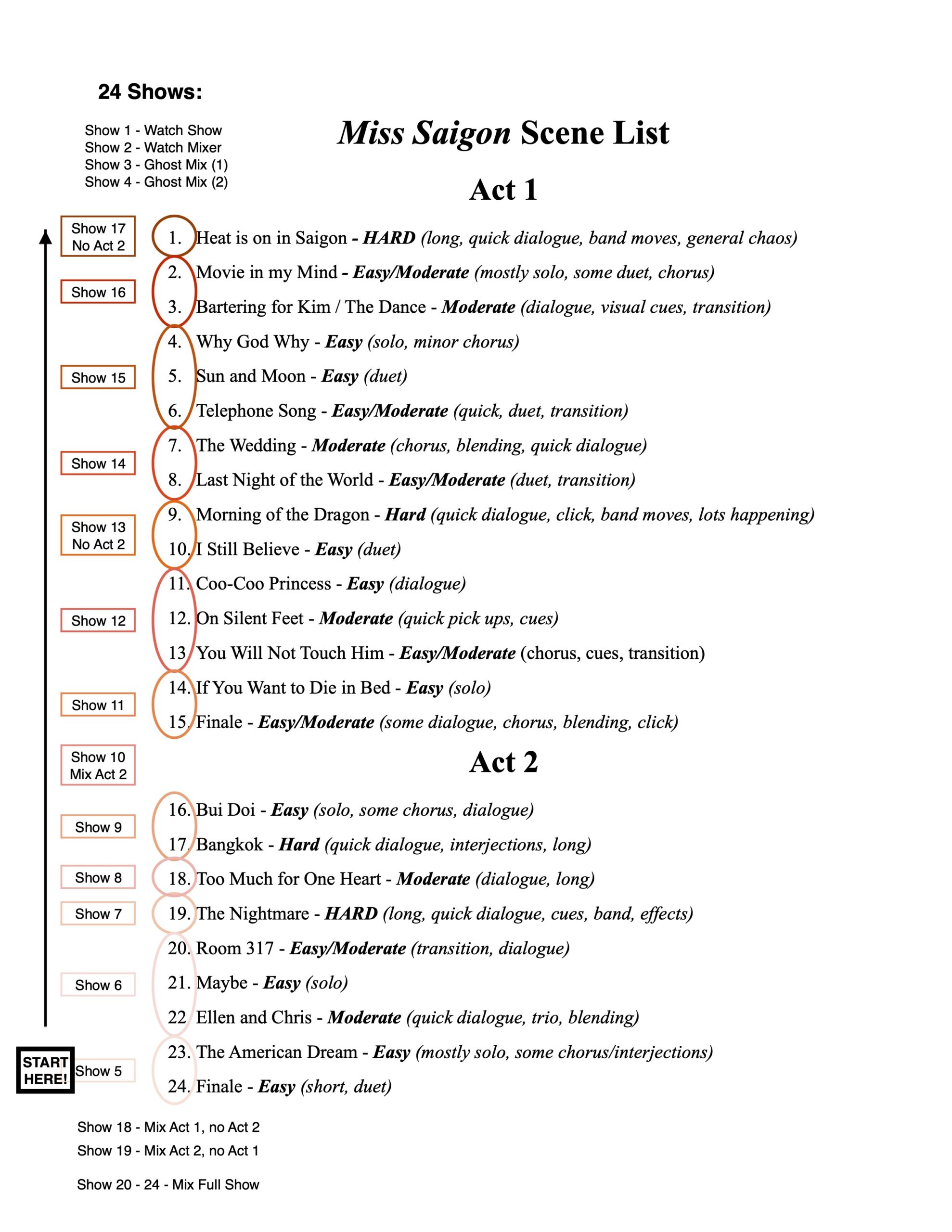

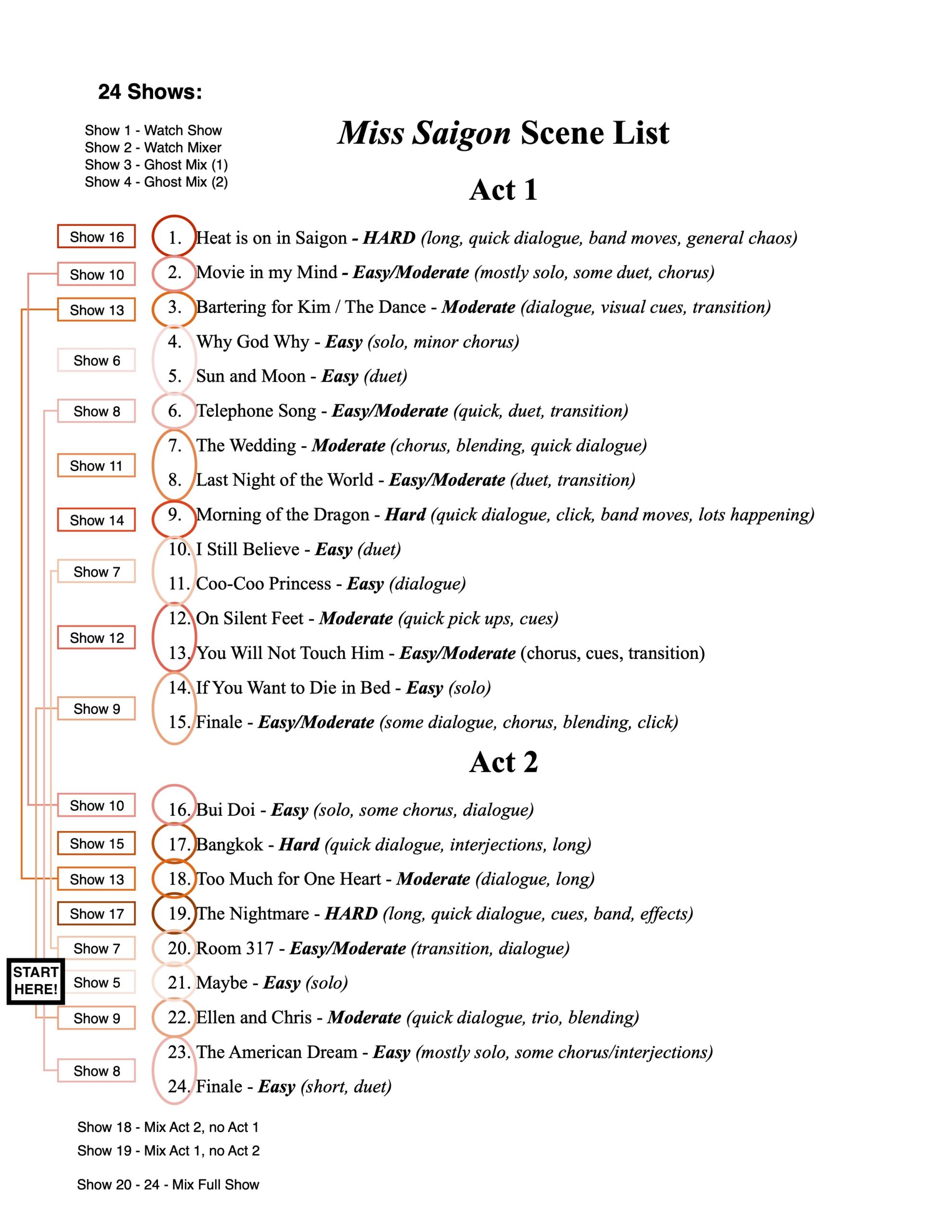

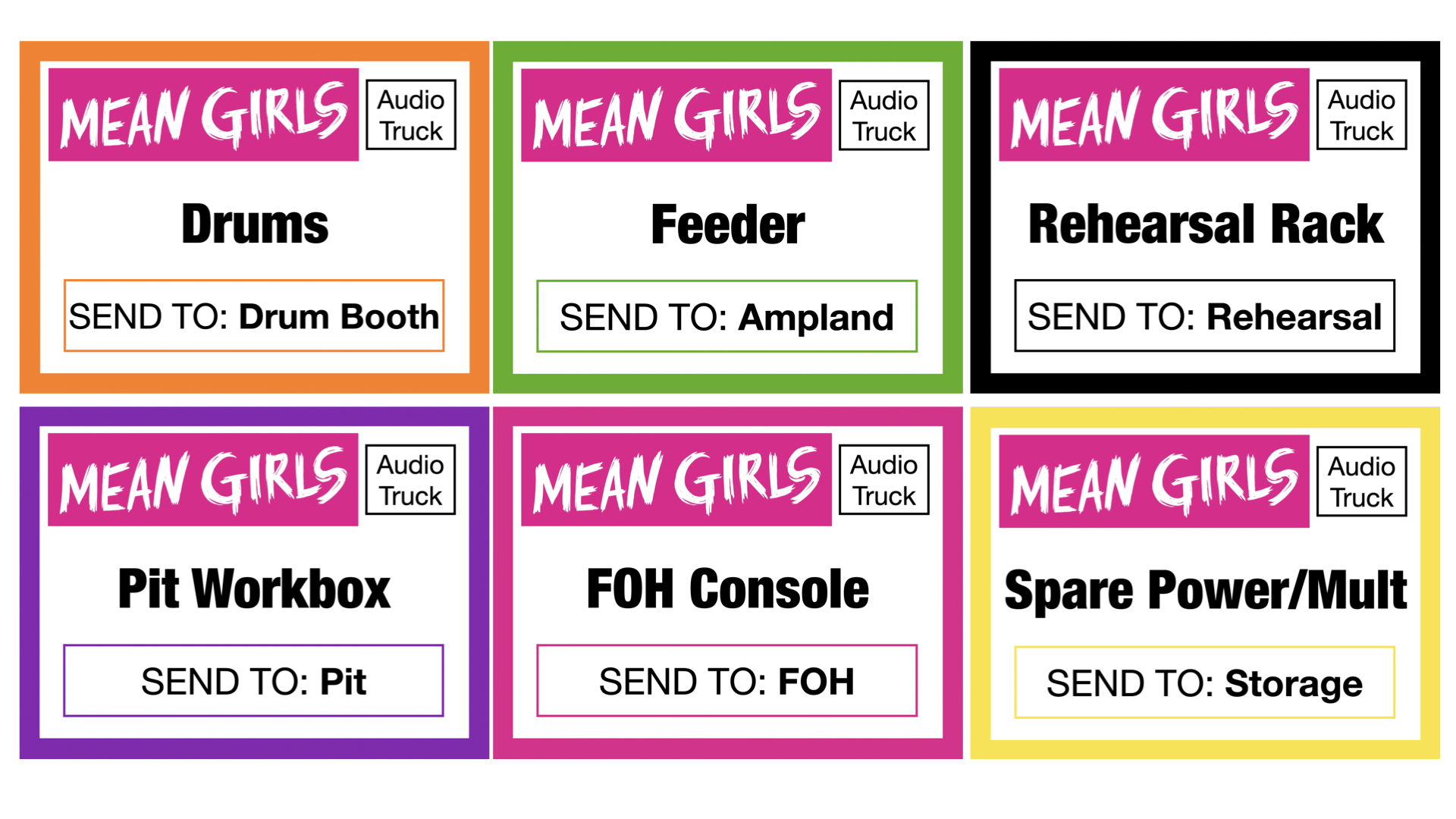

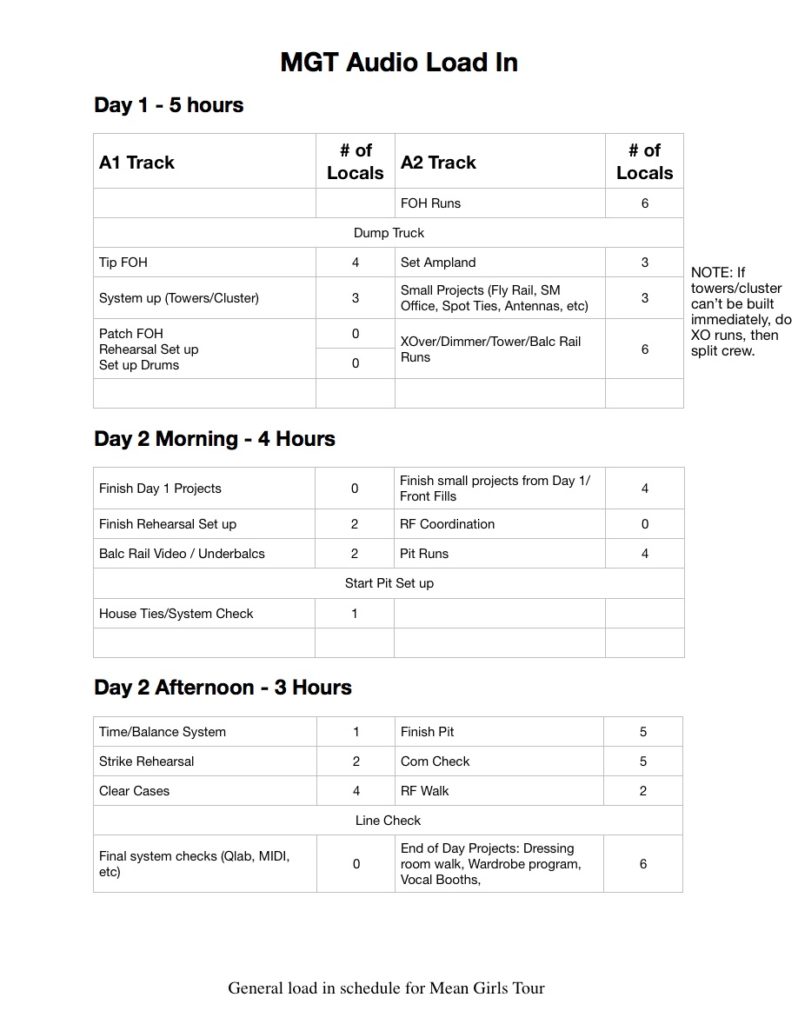

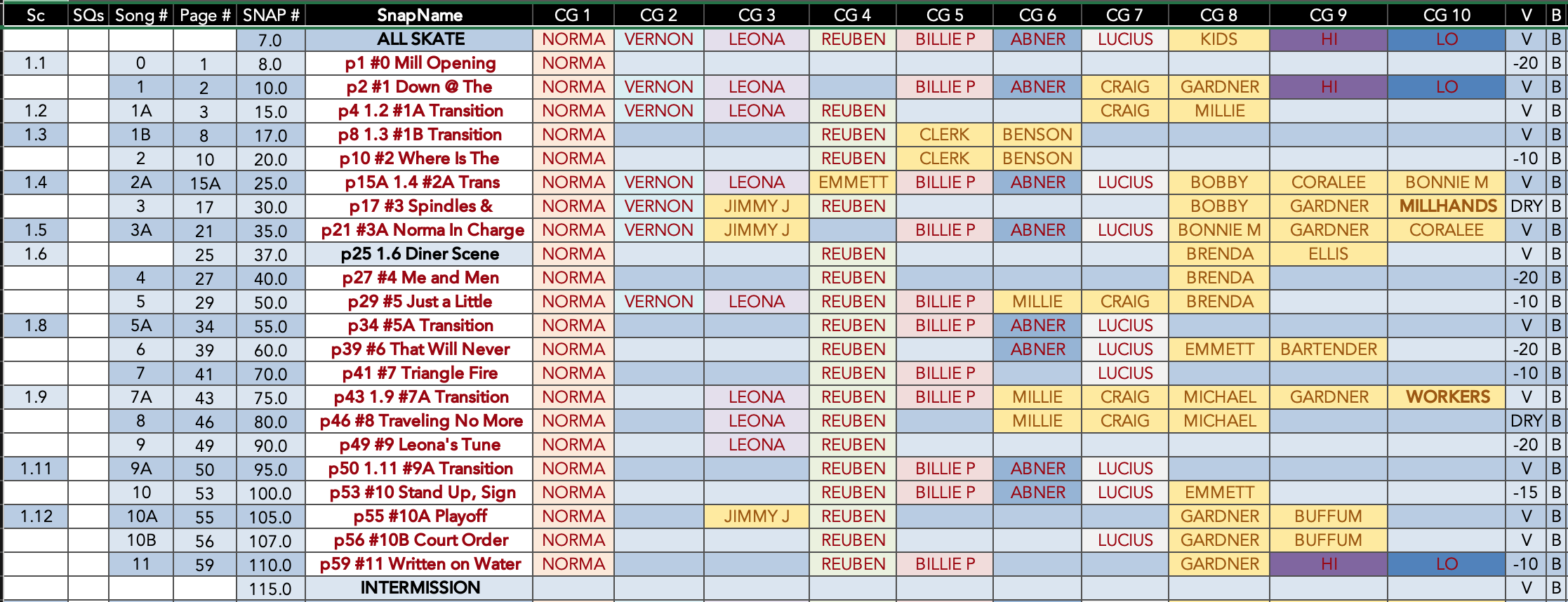

My personal favorite way to program a workshop is using what I call the “All-Skate” scene. Basically, I analyze the script, figure out which characters have the most dialogue, and design one console scene with VCA assignments that will work for most of the show. For a standard musical, every principal will be assigned to their own VCA, with the ensemble in two groups. That way if the writers suddenly throw in a new scene/song, you’ll be ready to mix along with minimal adjustments. Here’s what that looked like in a workshop I mixed last fall:

Once you’ve got your all-skate scene written, build every subsequent scene out of that template and only change what you need. On a standard musical you might eliminate characters who don’t speak from your VCAs; don’t bother with that here. The likelihood of things changing and people getting added is so high that you might as well be prepared. So, to return to our example from above, here is what my programming for the whole show of Norma Rae wound up looking like.

You will notice from the color coding that I have changed as few VCAs as I need to in each scene to make the programming work. So, even if REUBEN isn’t in a scene/song, I didn’t bother clearing him out unless I needed VCA 4 for something else

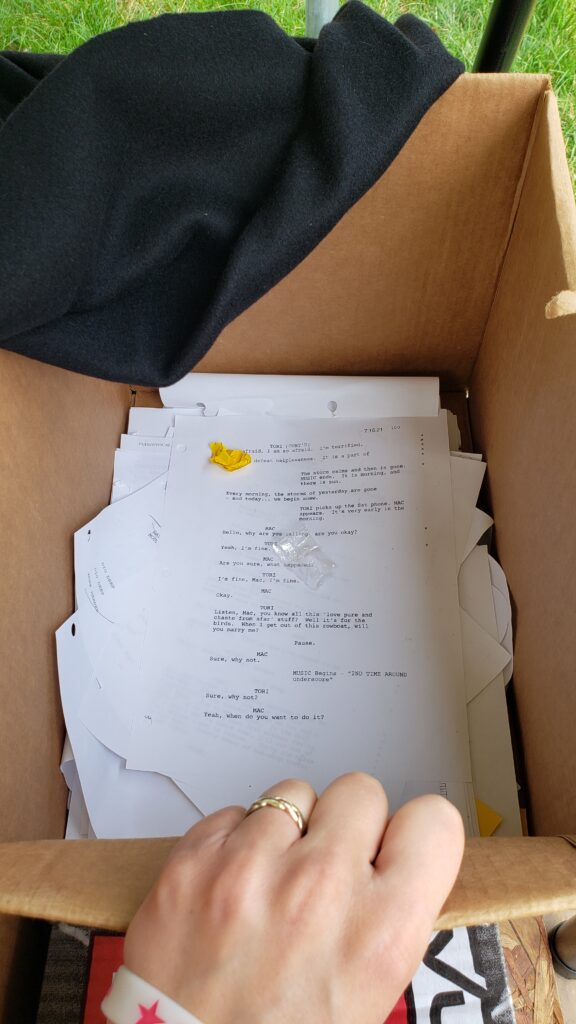

DON’T GET FANCY with your book.

I am a stickler for a clean book, but there’s not going to be time. Use all your shorthand. Be ready to erase, rewrite, rip out pages, glue in new lines, etc. For the last reading, I mixed I simply crossed out all the stage directions by hand with a thick pen and did most of the write-ins with white-out and pencil.

On a reading in particular, you’ll most likely not be changing your VCA assignments as much, since you’re just mixing on wired mics that are in fixed positions, and the people speaking at them are the thing that is changing. Make yourself good notes so that you are always on top of who is singing where. If a whole page is just 2 or 3 people having a conversation, I’ll simply write a huge “2+3+4” in the top right corner of the page and then park the mics up. That way I’m not having to follow the dialogue as precisely and I’m not risking missed pickups attempting to be fancy and do a proper “line-by-line” when I don’t really have to.

If you read music notation, working off the piano-vocal score is going to be very useful here. I found myself constantly scribbling on the PV for the 2 workshops I mixed last year, because even with a great script PA, sometimes the score is just more accurate, and gives you a better idea of what’s going on in a song. I mixed only a few songs on the score for the actual presentations, but even so, I was constantly referencing my PV notes.

I know some folks are moving towards digital scripts, but until you are a true workshop expert, I would highly recommend sticking to a good old-fashioned paper script. It will allow you to make changes more easily and get your thoughts down more quickly. You’ll also be able to process subtle and small changes in the room that might not make it into the PDF of new pages that will eventually be emailed out. This is especially true if your show isn’t going to “freeze,” meaning even once you’re into presentations the creative team might continue to make changes.

USE YOUR ALLIES AND GET INFORMATION

Much like on any new musical, the script PA and the music assistant are going to be your new best friends. They are the folks who will be the most aware of what’s changing, who sings when, and what email threads you need to be on. Make sure you are not left out of the conversations that are relevant to you, especially if folks on the team aren’t as experienced or used to working with a mixer. Sometimes they don’t realize how much work you’re doing, and why you need all this information. But hopefully, once they do, they’ll be on your side and will do everything they can to help you out.

BRING YOUR ARSENAL

The workshop mindset requires you to work quickly. There is so little time. You’re basically doing an entire rehearsal, tech, preview, and run of a new musical in two weeks. Be ready with your A-game and all your tricks, hacks, and cheat sheets. Be ready to program quickly, either by keeping things simple, using the “all-skate” method, or some combination of the two. In a reading, consider not using scenes at all if you don’t need them. And above all else, breathe, smile, and have fun. You’ve got this!

If you have any further questions about mixing developmental works, feel free to send them my way and I’ll try to answer them in a future post. I’m always eager to hear from my readers about what topics they would like to learn more about, so all suggestions are welcome!