I have always been excited by sound design and its potential for storytelling as well as the evolving technology of the industry. At the start of my career, I was mainly a theatrical sound designer and engineer. Then I got a gig designing sound for Halloween Horror Nights at Universal Studios. I had never considered theme park attractions! Since then, I have kept getting sound design work for immersive theater and themed events. There are many types of live, immersive storytelling events out there: immersive theater, theme parks, art exhibits, and experiential marketing pop-ups.

When sound designers work on live immersive projects, they must have an understanding of the story as much as how to implement the technology. The appreciation of the story helps the sound designer make decisions about the creative and system design that will not break the audience’s suspension of disbelief. It can be harder to pull off the suspension of disbelief in immersive settings than in more traditional venues, but the payoff is extremely rewarding!

I want to discuss sound reinforcement of mic’d performers and instruments in this article, but it is already very long. The science there does not really change, though perhaps it gets more complicated! So in the interest of length, I will cover very general speaker placement, creative choices, and the collaboration process.

Sound Systems for Traditional Venues vs. Immersive Spaces

Let us begin by discussing the fundamentals of sound systems for proscenium spaces as well as immersive spaces, and the differences between them. Understanding the components of sound systems for more traditional venues informs much of the decision-making behind building immersive sound systems.

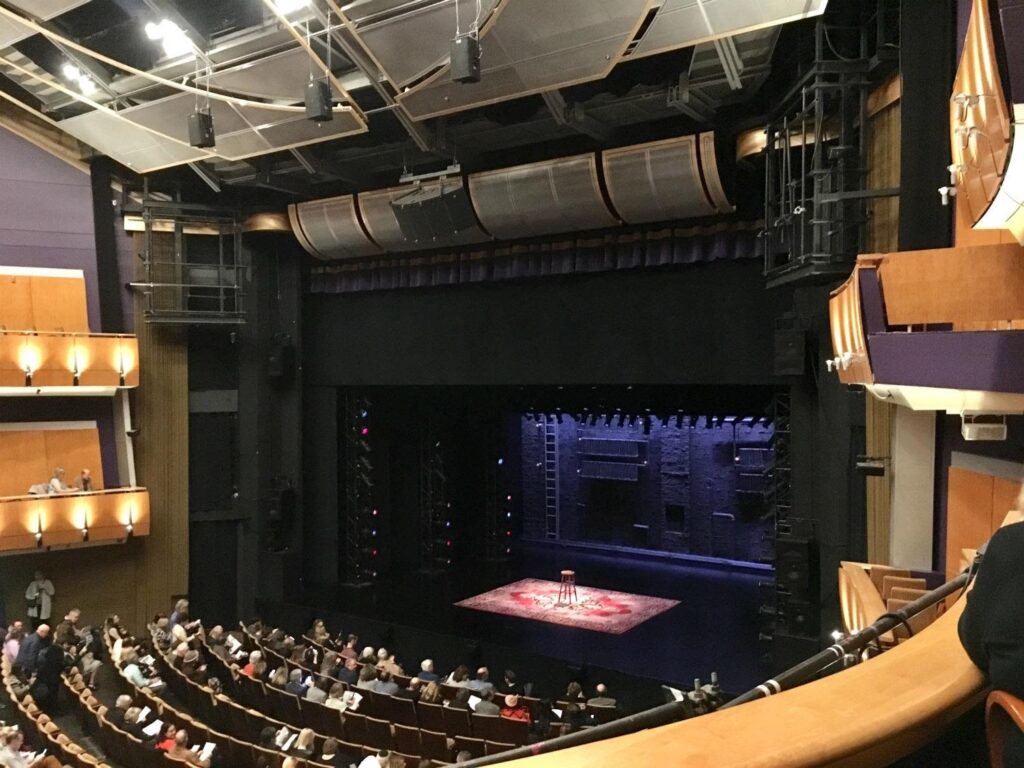

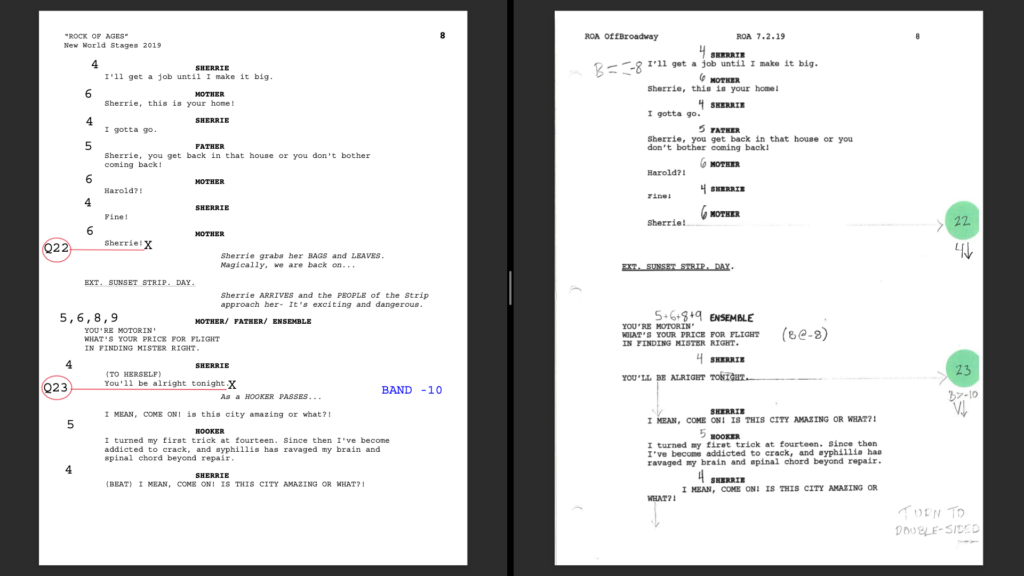

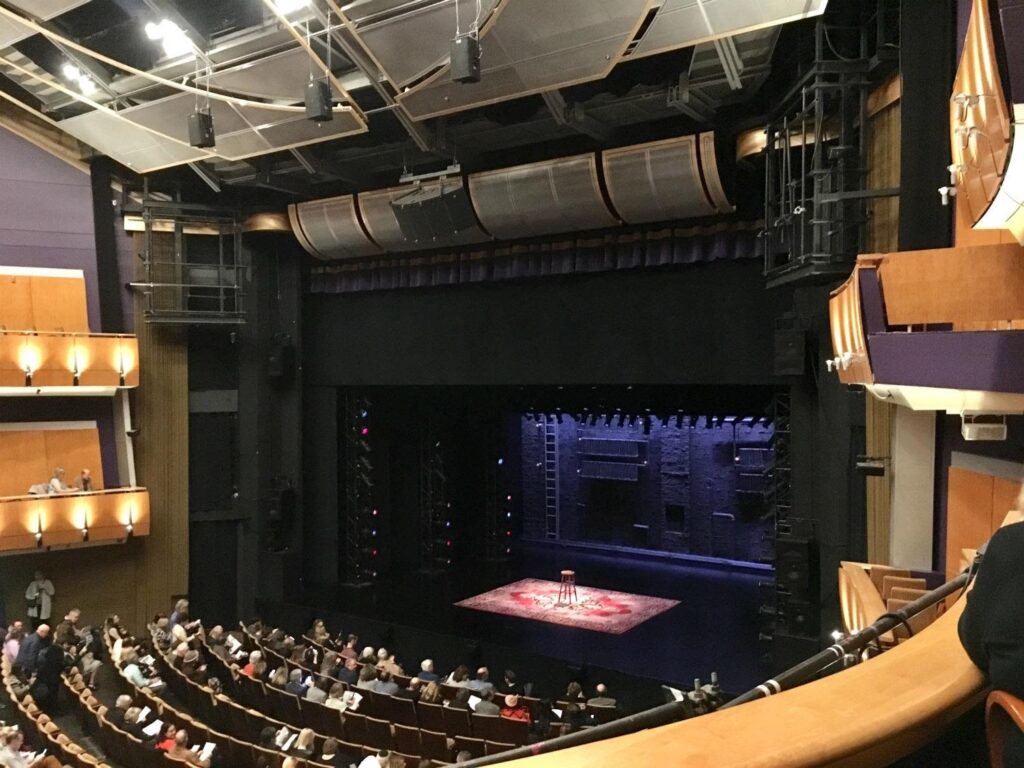

Proscenium stages have three output channels as the core of their systems: left, right, and center. Focused and tuned correctly, those three speakers (or speaker arrays) deliver a sound image where the audience perceives sound as coming from the stage, rather than any one speaker. The optimal place to sit to get the best sound image and mix is referred to as the “sweet spot.” Three channels make for good sound coverage of an audience, where most people are sitting in that sweet spot. It also provides more bussing opportunities for a good, intelligible mix. Music is sent to the left and right channels, with vocals in the center channel, so they do not compete as much with music. Then you add subwoofers delivering the low frequencies, making for a full mix.

If you look closely, you can see the center cluster, and then speakers on the left and right sides of the stage. Photographer Mike Hume. (Source: Ahmanson Theatre: https://losangelestheatres.blogspot.com.)

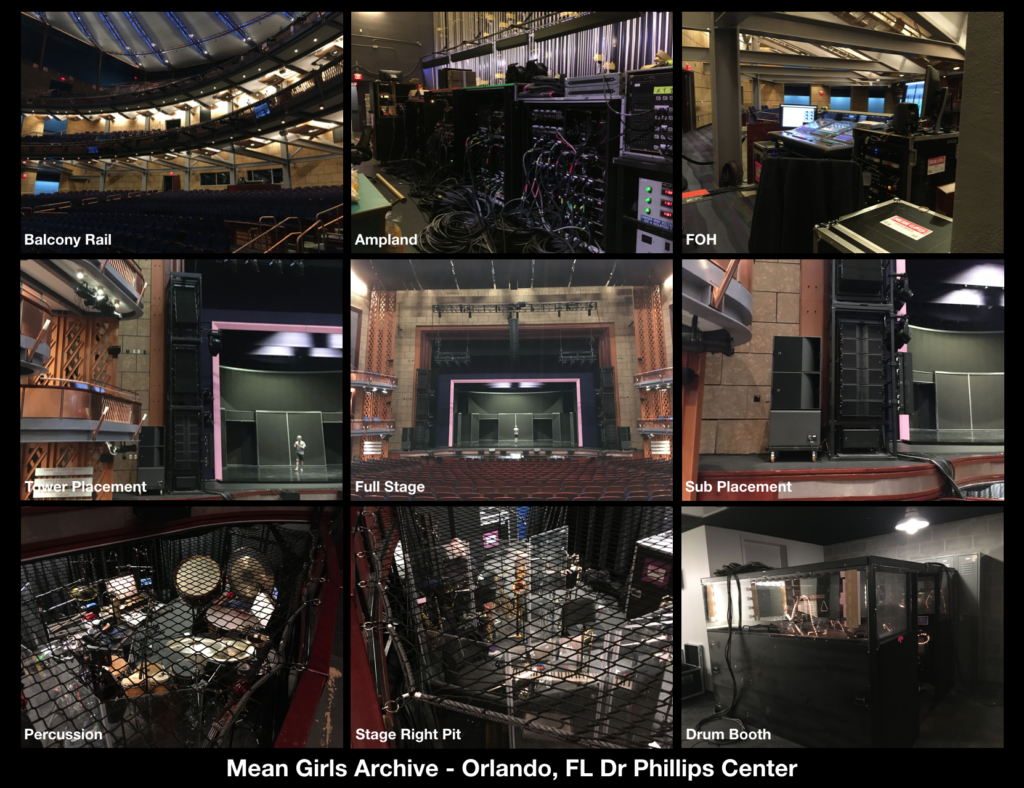

Larger venues with proscenium stages generally also have surround and delay speakers so that sound can reach seats out of the sweet spot (and let’s be honest, they are also for cool panning effects). And then there is usually some type of monitoring on stage for the performers, separate from the sound system for the audience. Two other characteristics of traditional venues: the audience is seated in one place the whole time, and the room is typically designed and acoustically treated for live performance.

Similar to traditional stages, if the immersive sound designer has the budget they can and should buss music, sound effects, and ambience to different speakers for an optimal mix if they have the budget. Truthfully, because of where they end up placing speakers and budget restrictions, they may have no choice but to put multiple sound elements through the same output.

Differently from proscenium stages, immersive events are typically installed in found spaces, and the performance happens on the same plane as the audience. Actors usually mingle and talk to audience members. This could mean that speakers for the audience are also used as actor monitors, which can present acoustical problems if your performer is wearing a microphone. Even with experiences where the audio is all pre-recorded and played back, there are acoustical challenges in immersive spaces since they are not initially designed for live performance. However, you can use acoustics to your advantage and have a lot of fun!

The sound designer’s job is to trick the audience into believing that they are in the same world as the actors. Immersive experiences are even less forgiving of seeing speakers because the sound is supposed to feel as if it is generated within the world and not through a sound system. This challenge sounds like a real bummer, but I implore you to embrace it. So how do we do that?

Collaborate Early and Often

Before we can talk about system design for immersive spaces, we need to talk about what kind of information you need before you can make those decisions. Immersive events are highly collaborative, and it is important to make sure everyone is on the same page.

First, you will receive a client deck or presentation. All the vendors (sound, video, lighting, costumes, set, props, special effects…) will have a meeting with the client or director to get a rundown of their vision. Everyone should receive a paper version of the client deck. In a theatrical setting, this meeting is called a kickoff, first production meeting, or designer meeting. Whatever paperwork you receive during that meeting, consider it your show bible and keep it handy. It may even answer the next few questions covered here.

Next, schedule a site visit. Inquire about power capabilities, since that will determine most of your sound system. Ask about where power is being drawn from. Many immersive productions rent a generator. Some buildings might have the means to use in-house power. If that’s the case, ask how many circuits they have. You might not be able to have quite as many speakers as you would like, and you need to determine your compromises early on so you can let your director know about limitations in the event that the production does not have the budget or facility requirements to support something they have asked for. Find who is in charge of power (usually the best boy or master electrician) and have a discussion about having separate circuits from lighting, and where you need to plugin as soon as possible. You will be dealing with enough unique issues without having to troubleshoot a ground hum.

Venues made for performance have the infrastructure for running cables and hanging speakers; site-specific performance spaces do not. Begin to ask questions about how you can hang speakers at the site visit, as well as cable runs. Ask if you can drill into walls, and what they are made of. Can you hang rigging points from the ceiling? Talk with the lighting, show set, props, and technical direction departments about their plans for running cable so you do not run under theirs. Inquire about whether anything will need to be struck between shows. These are all considerations that will influence your system design. Expect to have these conversations throughout the design phase as every department moves closer to install.

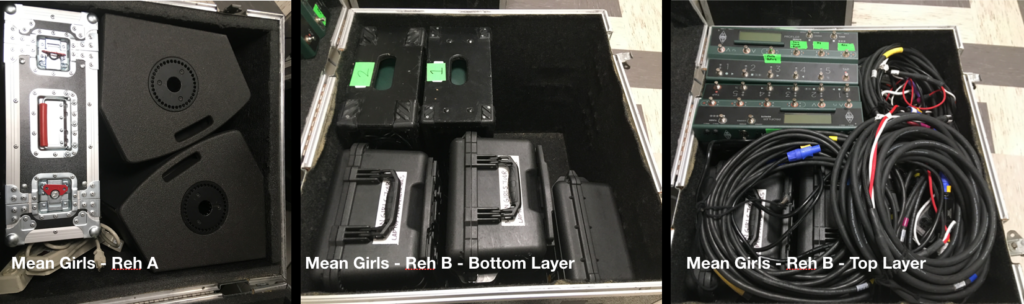

Ask your production manager, director, or set designer about backstage areas (and the traffic going through them) right away. Once you spec your console, show computer and other rack equipment, send your production team exact measurements and rack elevations with power, front and rear access space, and air conditioning/airflow requirements. Real estate is often tight in backstage areas, and your “front of house” area might need to be shared with lighting, video, and even actors in standby for a scene. Put rack and equipment dimensions on your sound plot and perhaps even map out cable runs so everyone on the team has an idea of available real estate in these backstage spaces.

Make note of acoustics, and ask about audience pathways. Where the audience travels will affect where you put your speakers and how you run your cables. Also, ask about audience capacity and flow. If one audience group enters an experience while a previous group is in another room further ahead, you will need to know that to consider sound bleed, which could affect creative choices.

This article iterates on this point throughout, but I’ll say it again: it is in your best interest to collaborate early and often with the art department. Reach out to the set designer and ask for ground plans and elevations at this stage so that you can draw up a speaker plot, and begin to have conversations about hiding speakers.

Finally, ask about emergency procedures. Traditional venues have obvious exits and a voice of god mic. Immersive events might need to utilize actors to guide the audience out of an experience, and the team should talk about whether they cut sound entirely when an emergency happens. (Generally speaking, they should.) Does someone get on a mic and make a live announcement or is there a pre-recorded cue? Any number of emergencies could happen, whether it is a technical failure, the weather, or a situation where the audience and/or cast are at risk. Cover all of the possibilities. Your director should decide at what point an emergency is serious enough to trigger a show stop, and what the procedure for a show stop is, and how the show is resumed. The team should determine all of this together, and you need to know what the emergency procedures are as the sound designer so you can program a show stop cue. The emergency system should be provided by another vendor because you as the sound designer are probably not current in things like local fire safety and emergency services. You may provide an emergency paging system separate from the show system if you are asked, but have a conversation with your producers about how that is outside of the scope of sound design and that you will need a separate budget.

The Speaker Plot – Ambience

Speakers for an immersive system can have any of five purposes: ambience, music, spot effects, voiceover, or live reinforcement. You can separate out what goes where, but you often end up sending multiple elements through shared outputs. This is because there are many constraints in designing a plot — budget, scenic design, placement of lighting instruments, and of course how the sound waves from speakers will interact with space and other speakers.

Speakers for ambience, music, narrative voiceovers, and emergency announcements work best above the audience. The distance makes for good coverage because they are in the widest part of the speaker’s throw. Additionally, placing speakers low means sending your acoustical energy into the legs of your audience, which means losing a lot of energy needlessly since sound is not aimed at their ears! If your speakers are going to still be visible to the audience even if they are above them, put them behind the audience path. This does not work for every application — if you have a staged area with mic’d performers, this is not the solution because the sound image has to be where the performers are staged — but it works much of the time.

I prefer to use a lot of little speakers with sound pushing through them at a quieter volume. (I really like the Meyer MM-4XPss.) This makes for more consistent coverage and a believable environment. However, the budget does not always allow for a ton of tiny speakers. In this case, you can compromise with one or two big speakers. Always prioritize coverage — it can really take an audience out of the world if they walk through a dead spot. Place and focus larger speakers in such a way that they cover the whole room, and send music, ambience, and voiceover through it. Of course, mix all those elements in such a way that they are balanced and you don’t blow the speaker!

Subwoofer placement is definitely challenging because they are often too big to hide! If you can place a subwoofer outside of a room against the exterior wall, it should do the trick. I have also hidden them behind set pieces. More about subwoofers later.

A note about having music in stereo, because I have run into it with some artists. Yes, having a stereo image for the music is really important. If you can get away with having two speakers in a room for a left and right channel of music — do that. It also depends greatly on audience path, room size, and budget, and physics. A stereo mix requires that the left and right channels arrive to the listener at the same time. To accomplish that, the left and right speakers need to be equidistant from each other and the listener needs to stand in the sweet spot between them. In an immersive setting where the audience is moving, it might not be possible to place speakers in such a way that a good stereo image is delivered. In most immersive settings instead of stereo or 5.1 Surround Sound (which are valid in situations where your audience is static), you will often have a massive distributed audio system. This means that more often than not mono audio files are preferred so that you can place them exactly where you want them without worrying about how they are tied to something else. Essentially, imagine not building a 5.1 system, but a 32.10 system or larger. Again, have stereo speaker pairs if you can swing it, but be aware that this is another potential compromise. Know the science so you can explain your decisions.

If you are working with a composer, talk to them about giving you stems so you can put individual parts of the music wherever you both want. It is incredibly useful and efficient to mix the music as needed in the room, to hear how it reacts acoustically.

The Speaker Plot – Point Sources

Another consideration is, what are some specific sound sources in a room? Things like telephone rings, radios, et cetera differ from ambience and music speakers in that they require the audience to perceive that sound is coming from the source. (There are other technical hacks you can do to make a phone ring on cue, but this article talks specifically about speaker placement.)

When choosing a speaker for a point source, consider what is going to play through it and where you are going to hide it. Is it a phone ring, and that’s it? Then it doesn’t have to be big. Or is the effect a loud car horn that requires a bigger transducer to push adequate volume? Also, have a conversation with the set designer about what props and set pieces are around the sound source. The ability to hide a speaker, and how and where it gets mounted, will influence what speaker you choose as well. Another fun note about point source speakers: As you attend tech rehearsals you might realize that one point source speaker does not have the volume or throw necessary for the whole audience to hear it clearly once you get bodies in the room. In these cases, you can use the ambient speakers as fills. Dial in a little bit of the sound effect to fill the room, but just enough so the main source is the point source.

One of the most challenging and rewarding things about system design for immersive spaces is hiding speakers so the audience does not see them. Send a plot to your set designer early and expect to change it several times. Include a key with speaker dimensions. Talk to the set designer and technical director about how you are going to mount speakers and get their input on the best materials to use to do so. If a point source speaker has to be behind something, talk about potentially using an acoustically transparent material. (Yes, I have had to explain that velour curtains will muffle high frequencies. It happens!) Or, be open to the challenge at hand and problem-solve creatively. Maybe the muffle will actually help the purpose of the effect. Or, can you point the speaker upward so it is not shooting directly into props in front of it? Or mount it under a table? This kind of out-of-the-box thinking is really satisfying!

Also, be sure to consider which effects you need to fight for. Often lighting and scenic design have very specific requirements, and that means sound tends to be the design discipline that moves or changes to accommodate them. But sometimes the way a certain element is described in the script or client deck means there are specific sound design requirements. In those situations, it is imperative to put your foot down with the other design disciplines. If an effect calls for an atomic bomb to go off, for example, then you will be needing a subwoofer, and the scenic team will need to accommodate space for that subwoofer in their design. Be a positive collaborator, but be firm, because you can not change physics.

Acoustics & Bleed

When designing for immersive events, you often have to figure out how to cope with bleed from the outside world and even other rooms within the experience. Many immersive experiences are pulsed attractions, meaning they have one audience group starting while people are halfway through the experience, or simultaneous scenes. This makes bleed a really important thing to consider. True isolation is expensive, and I have yet to see an immersive show try to make rooms acoustically isolated. Sound wants are often communicated after the set design, budget, and production timeline have been determined. Many found spaces are unforgiving anyway, such as reverberant warehouses. The following techniques talk about what to do when bleed is apparent, and you have done all you can with acoustic treatment and good speaker placement, tuning, and focus.

One tactic is to embrace the bleed! Evaluate whether it can actually help your sound design. A horror attraction can be made much scarier when people in one room can hear screams coming from another. The next technique is to compromise on what sound effects and music you use. If you have a cheesy piece of music that works for a comedic scene in one room that bleeds into a serious scene in another room, you might need to either lower the cheesy music quite a bit, notch out more present frequencies or potentially pick different music altogether.

The outside world can also be a consideration. I have really enjoyed watching experiences where the outside world is actually a part of an immersive experience. Once I saw a theater production that took place in a graveyard. The natural nighttime atmosphere blurred the lines between what was the real world versus the world of the play. (Super cool!) However, many immersive attractions exist independent from the real world. In this case, you can’t do much about it. Many attractions get around it by making sound and music really loud. And, as you get more bodies in a space, less of the outside world will be heard. And audience members are generally too captivated by the production to notice the world outside!

Regardless of the issue, as you make these discoveries, keep having these discussions with your director. Do a site visit early and anticipate these issues early on and talk about them.

Inspiration Tips

You can gain knowledge and inspiration without working on an immersive project. Everything you apply in sound design for immersive spaces falls under the scientific principles within Acoustic Ecology. As with any type of sound design, start by paying attention to the world around you. What do you hear and where is it coming from? How do things sound different from close up or far away? Keen awareness of the real world can influence creative choices as well as mixing decisions.

Learn all the sound science. Start by looking up the Doppler effect (the pitch of something ascending as it gets closer, like an ambulance siren), occlusion (something blocking a sound), phase cancellation, and literally everything about room acoustics. Research psychoacoustics and how people respond to different frequencies. In a similar vein, learn about loudness metering, because it is weighted by how humans perceive sound. To hear examples of an immersive mix without going to an event, play video games with headphones on. Larger AAA games (some indie too), implement all of these psychoacoustic principles.

Live immersive events are a very fulfilling frontier for those of us with theatrical backgrounds. The process and application are quite different and very in flux throughout, with a ton of collaboration. Understanding the science, forging positive relationships with other departments, and a lot of creative problem solving are the keys to pulling off the suspension of disbelief, and will level up the sound design for your future immersive projects!

Thanks to my editors for reading through this beast and providing feedback: Julien Elstob (lighting designer), Fionnegan Murphy (A/V Integration Engineer), Stephen Ptacek (sound designer).