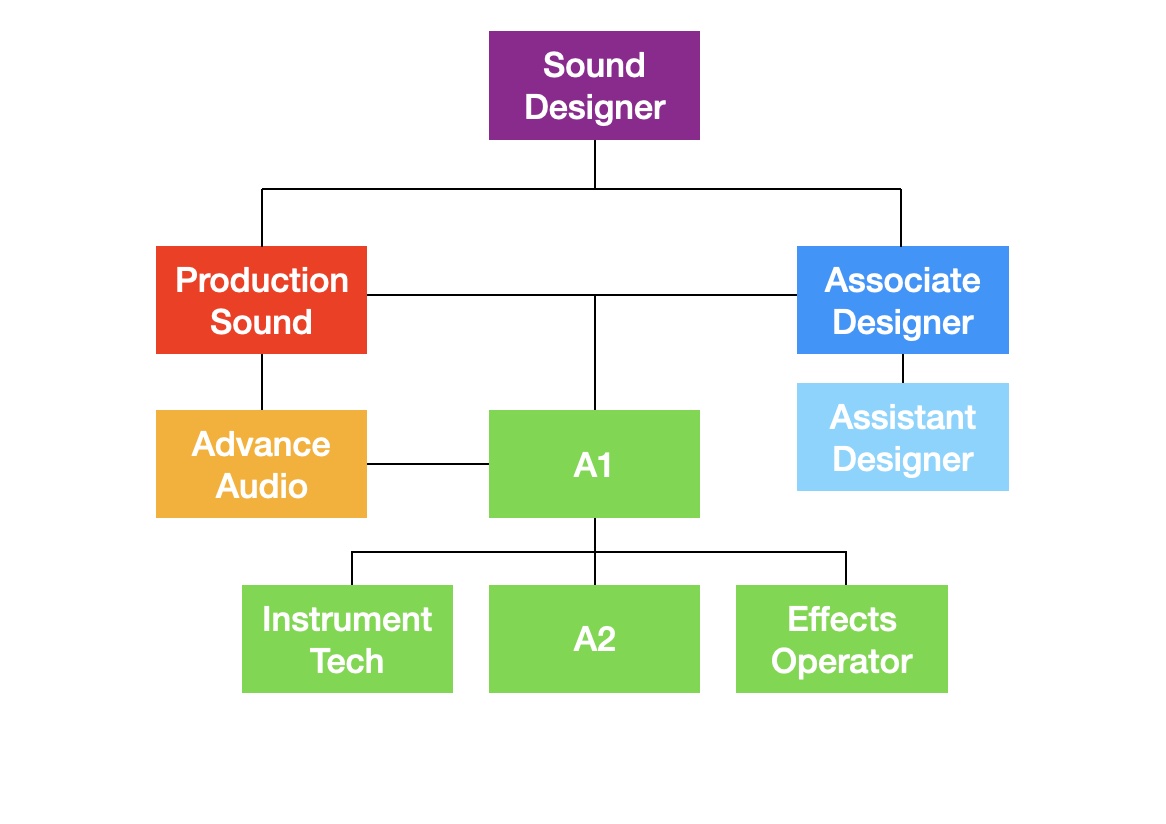

Ready, Set, Document

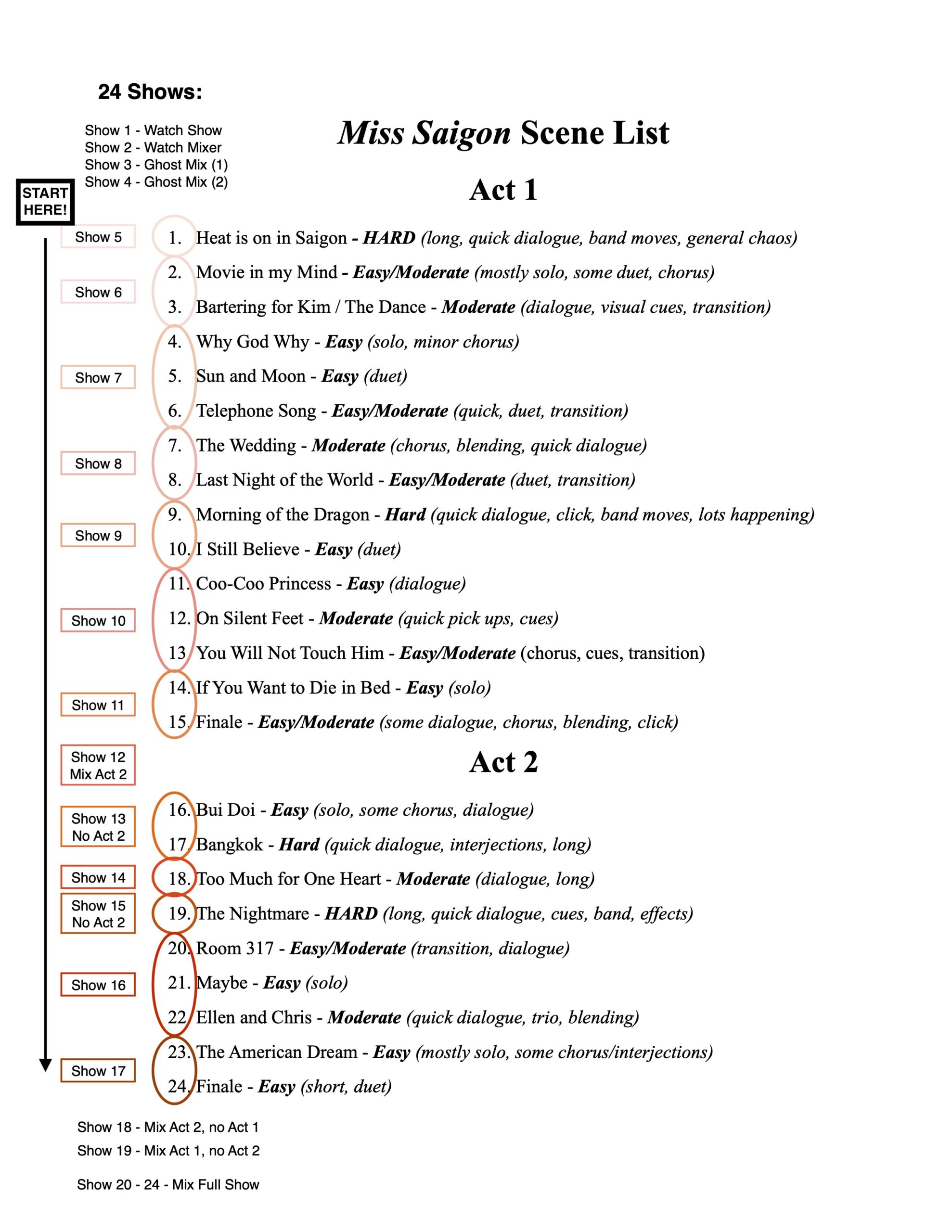

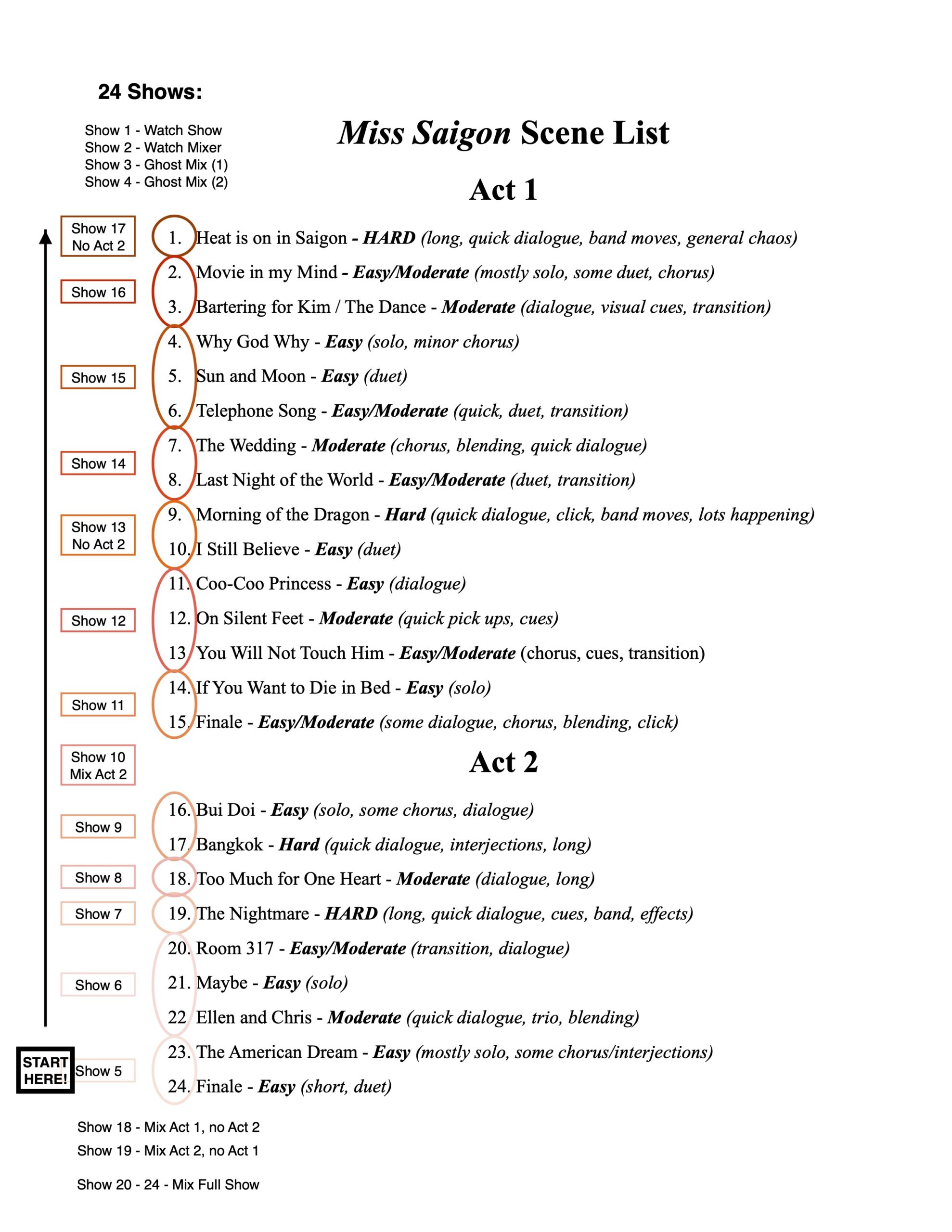

I’ve covered how I prep my script for a show and how I practice for tech in some of my previous blogs, but let’s take a deep dive into the what you can use to prep for tech and document a show for the run.

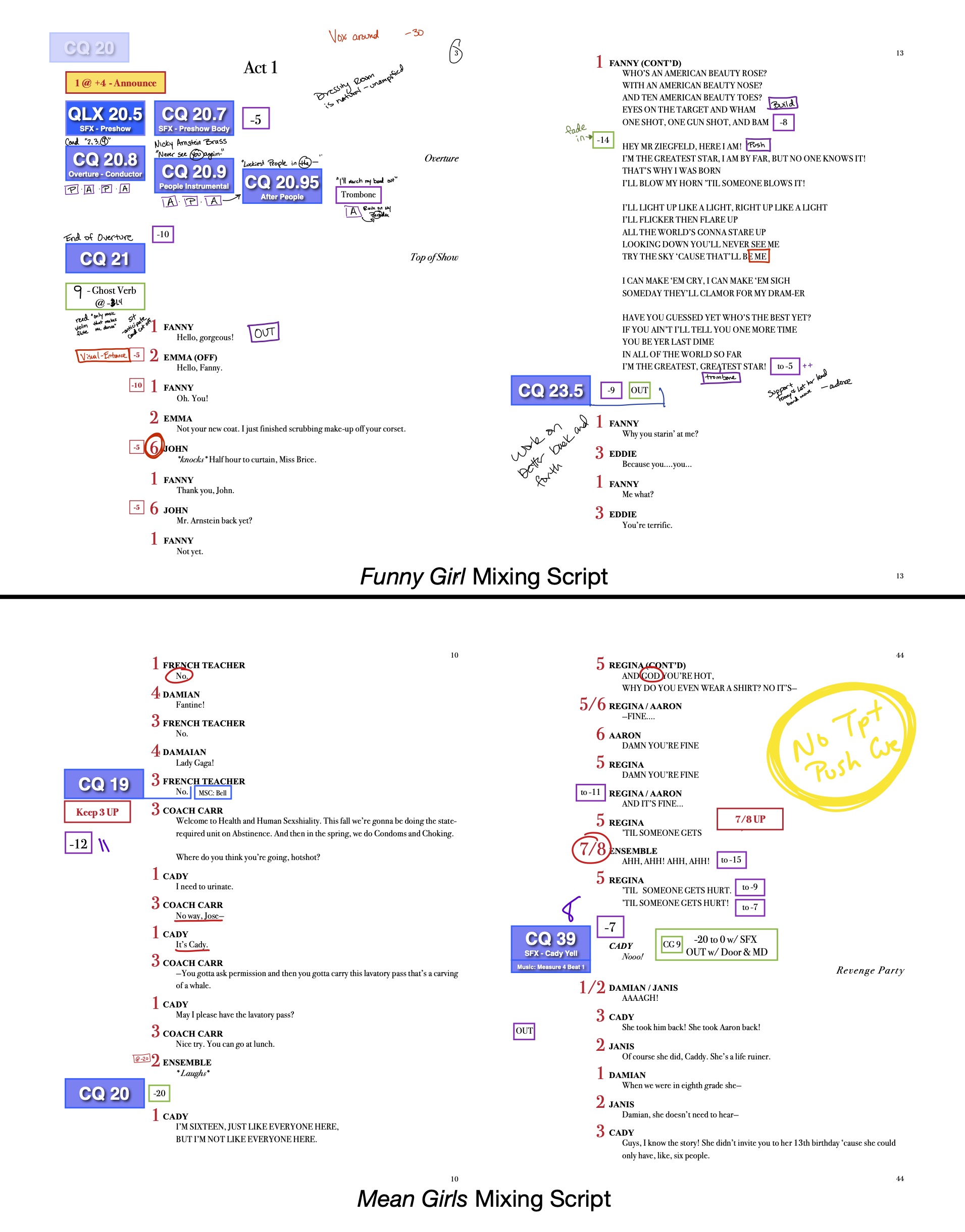

First up for preparation: get the script and and recording of the show. Details ad nauseam in this blog, but learning the show starts here. Personally, I retype the entire script (time allowing). This helps me get the show into my head because it requires me to go over every single word. While I’m typing (and any other time I can listen to music) I’ll have the recording playing in the background.

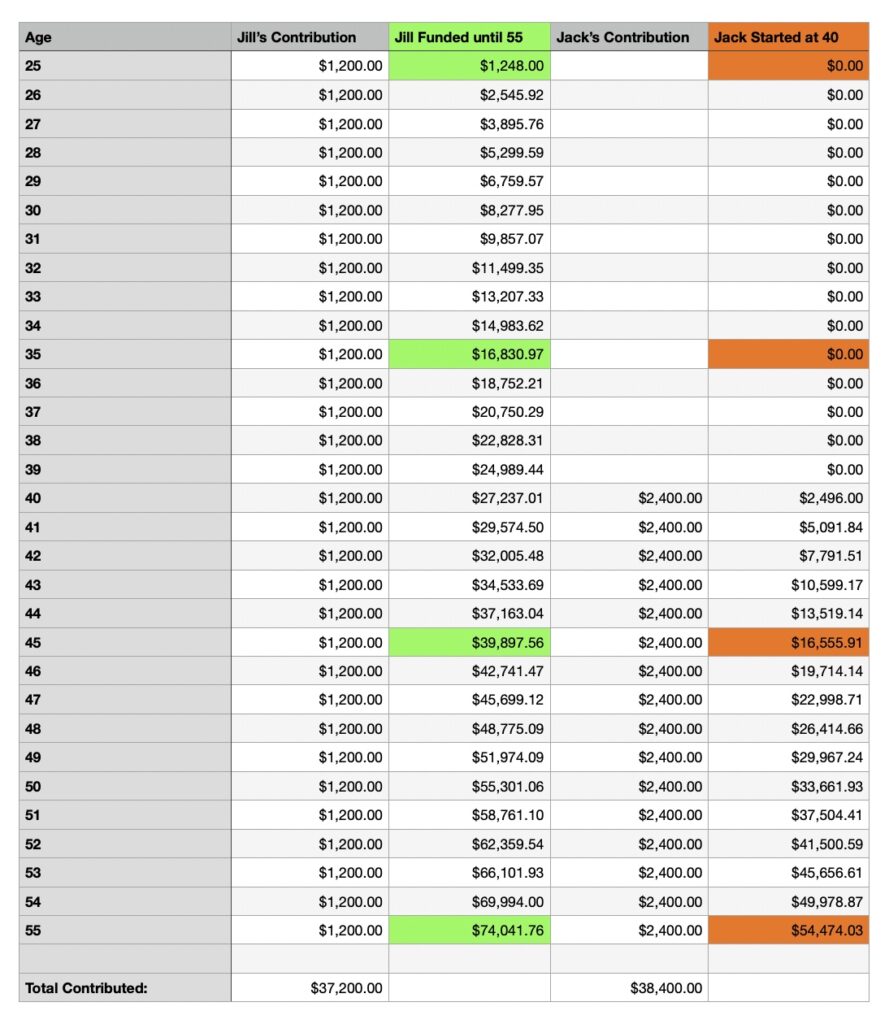

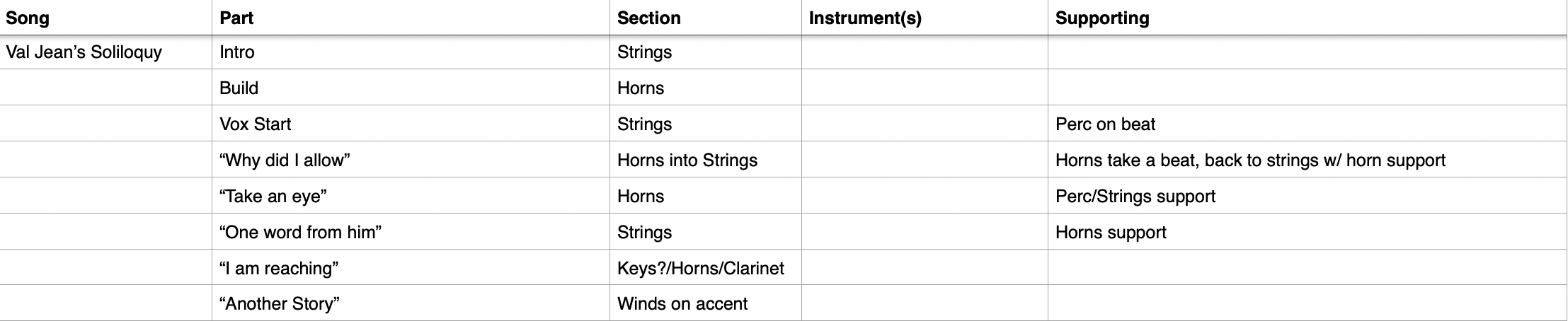

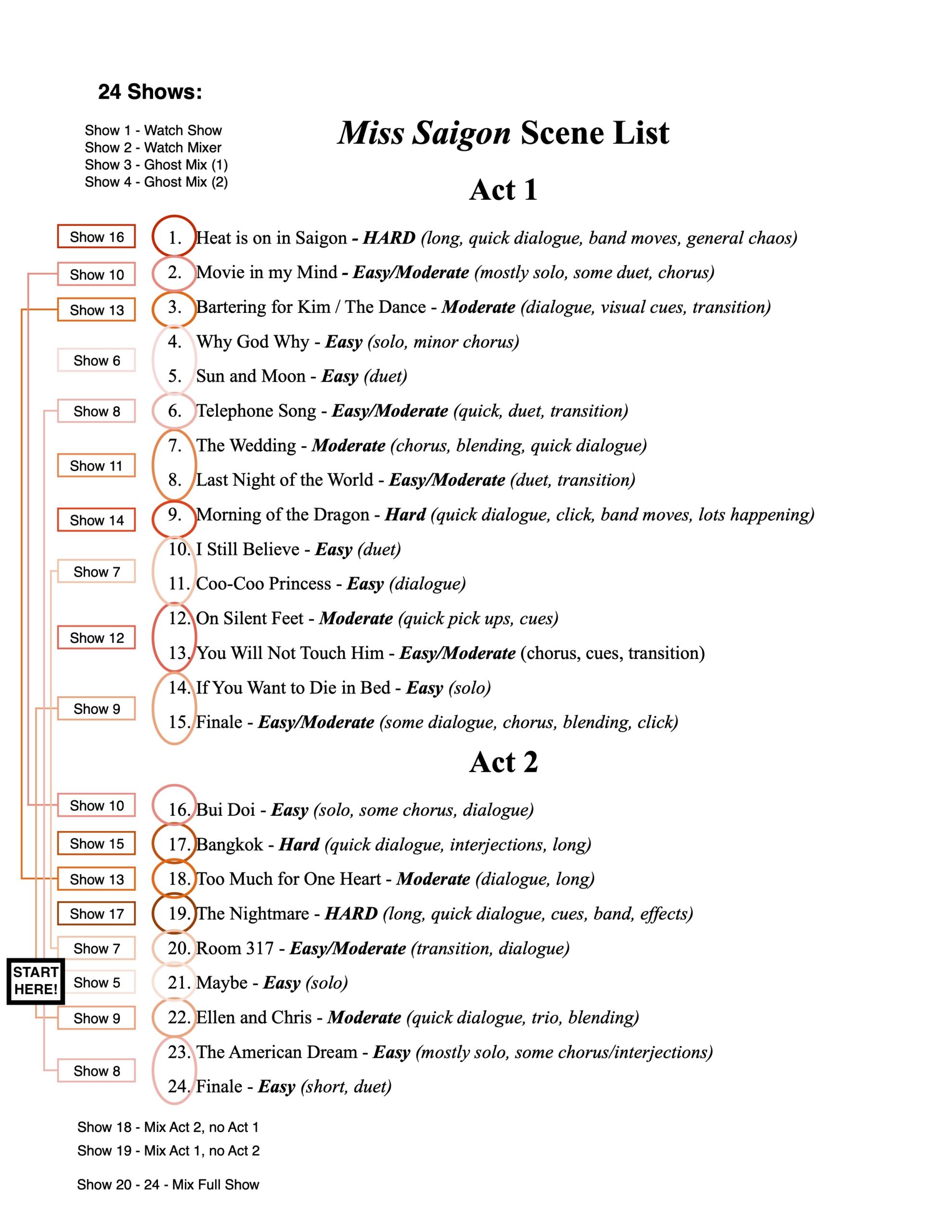

Once I have a version of the script to use for the run, I’ll do a pass through and rough in fader assignments and where to take cues for new scenes. (Details on different ways to do that in this blog.) Those notes create my next piece of paperwork: what I call a CG Breakdown. (DiGiCo consoles call their DCAs “Control Groups” so I use CG or DCA interchangeably here.)

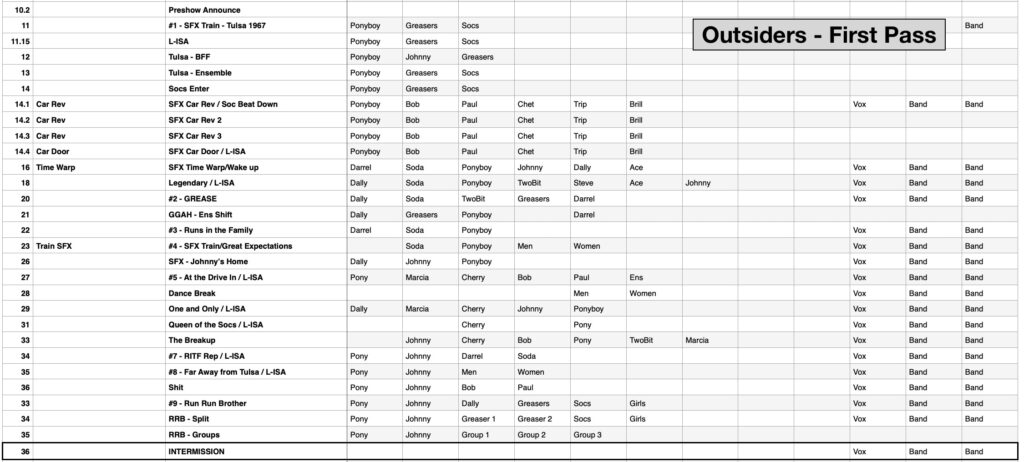

My breakdown is a spreadsheet where I fill in what each scene will look like. The first pass comes from what I noted in the script and it’s a rough pass. Things will change as you go through the show a few more times, but this gives you a starting place. Once it’s all there, I’ll look for patterns and how I can refine and simplify the mix: which people track from scene to scene or if someone’s in almost all of the scenes so it might make sense to keep them on a consistent fader.

When I was mapping out The Outsiders, my original pass assumed that Ponyboy, the main character, would end up on CG 1 for most of the show since he’s in almost every scene. What actually ended up happening was that he settled in on CG 3 for most of the show. In most of the scenes with other people he was usually the 3rd person to talk, and that also allowed me to place people around him. Dally and Johnny or Darrel and Soda became pairs on 1 and 2 for their scenes with him while Cherry or Bob usually ended up on CG 4 (with Bob on 5 when he was in a scene with Pony and Cherry).

Here is the first pass

Here Ponyboy bounces back and forth between CG 1 and CG 3 with a quick jaunt on CG 5 for a bit. If he continued from scene to scene, most of the time I put him on the same fader.

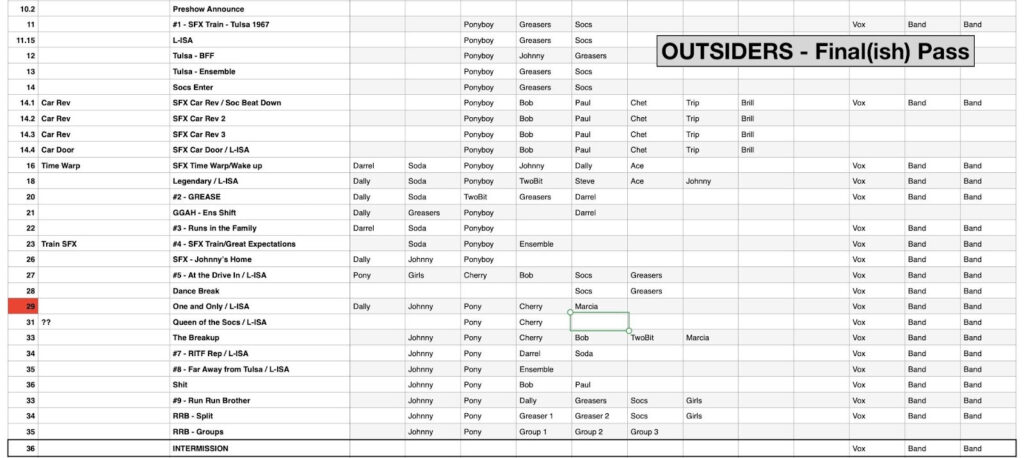

Then we have a few drafts later

Bumping the first couple scenes over puts Pony pretty consistently on 3, and then a couple scenes shift in the middle to keep him there (a few times it makes more sense to put him in speaking order). Moving him also doesn’t leave an awkward gap between him and Cherry for their scenes together.

This is a “Final(ish)” pass because things changed in tech and what we started with wasn’t what we ended up with, although they were pretty close.

The goal is to take the rough draft of DCA assignments and polish them to a more logical flow that you can take back to the script. Once you’ve made any changes from the original pass, you can start practicing. When you’re starting out in the industry you probably don’t have a practice board, so the tried and true method is using quarters. Grab a set of coins, one for each fader, and line them up on a table. (If you want to get more detailed you can grab some tape and make a line for each fader path with marks for where 0dB, -5, -10, -20 go.)

Honestly, quarters are much harder to navigate than regular faders, so if you can make it work with the quarters, you’ll have no problem once you get on the console. This was how I learned the mix for the first few years of my career.

As you practice, this gives you a chance to work through the script and the assignments you created. I like to go through the entire show at least once and then I’ll focus on the busy sections or transitions. This is the time where you can tweak things if something doesn’t feel comfortable, possibly changing fader assignments or adding in additional cues to make scenes smoother.

Once you feel good about the choreography of the mix, it’s all about repetition. Listening to the recording as often as possible and making sure you practice the trickier bits so you can check that it all really makes sense and feels cohesive.

At this point I’ll add in once last layer to my prep: I print out a version of the CG spreadsheet where I add scene numbers, cue lines to hit GO, and the names of all the CGs. (It’s basically what I’d have in front of my on the console without a script, because when I get to programming the show, I’ll use whatever note feature available so I’ll see what the cue line is for the next scene.) It looks like this:

Using this version of my breakdown I’ll do what I call “pointing through the show,” which means I’ll listen to a recording and point to who’s talking as they say their lines and mimic hitting go. Without the safety net of the script you can really see how well you know the show and easily identify the spots you need to review.

However, this is something I only do with an established show, like a tour, where the mix is already set. For newer shows that will change a lot during tech, trying to memorize the full show ahead of time isn’t as helpful.

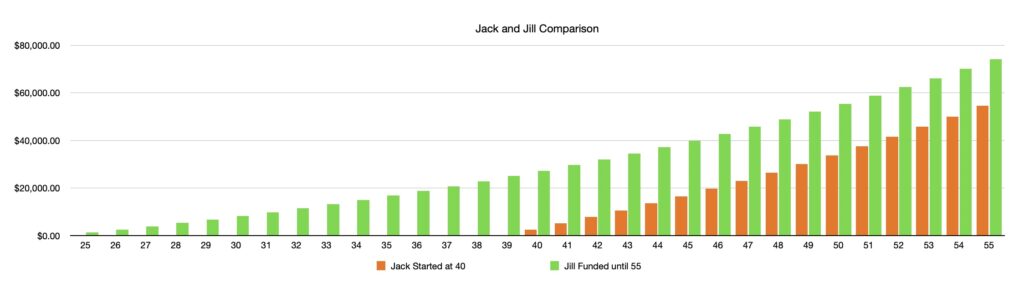

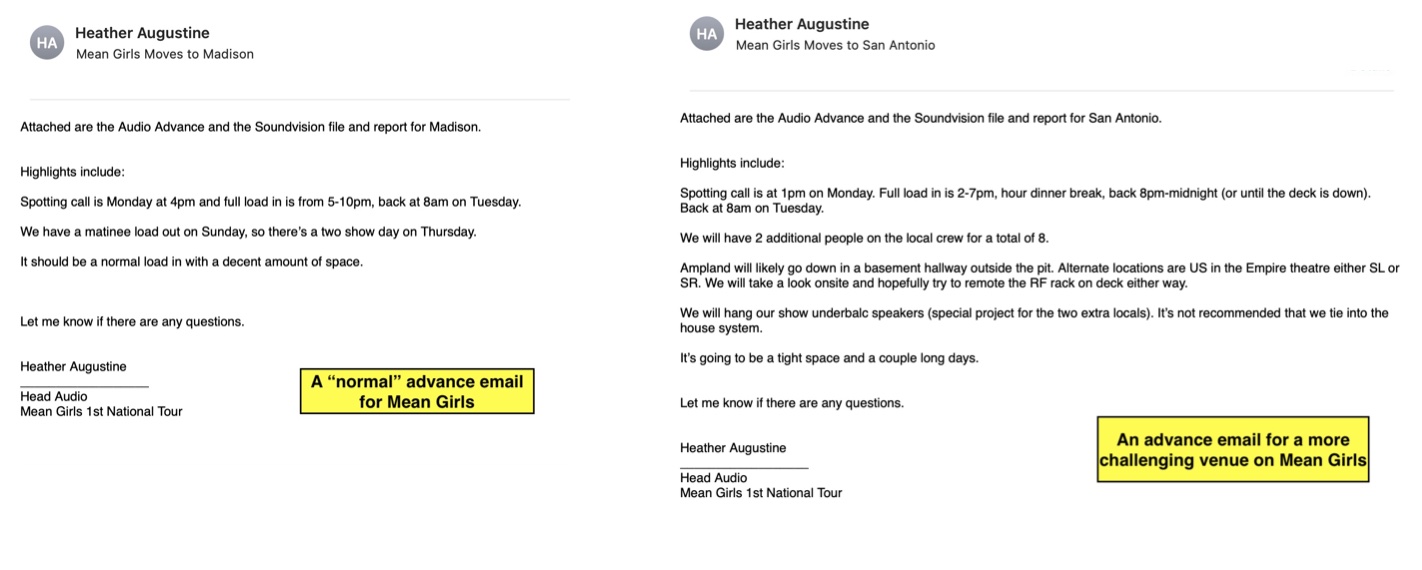

All of this prep gets you to a point where you hit tech with a solid understanding of the show and a plan for the mix. When you’re loading in, you will likely have to do some programming to set up the console and your DCAs. This adds one more piece of paperwork to the load, but it’s simply another version of the CG breakdown.

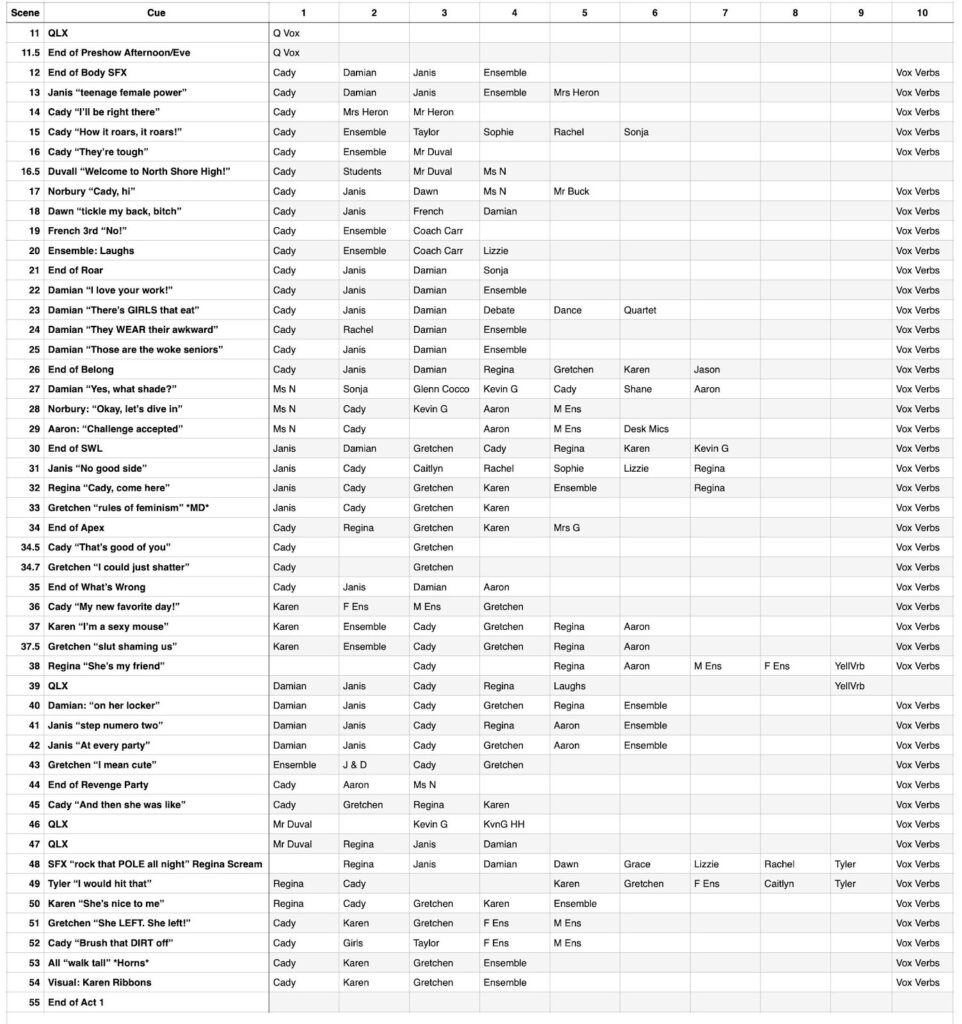

In this final iteration I add an extra row underneath each scene and add who’s in that control group if the name doesn’t already tell me, either because they have a different name in the script (in Mean Girls the ensemble all had character names for some scenes) or they’re grouped together in some way.

Here’s an example from the show

This gives me a comprehensive document so I know exactly who should be on what fader in each scene. Sometimes you’ll have to go to the music department to find out who’s singing which part in a scene or Stage Management to know who says a line if you have ensemble numbers for the actors but character names in the script.

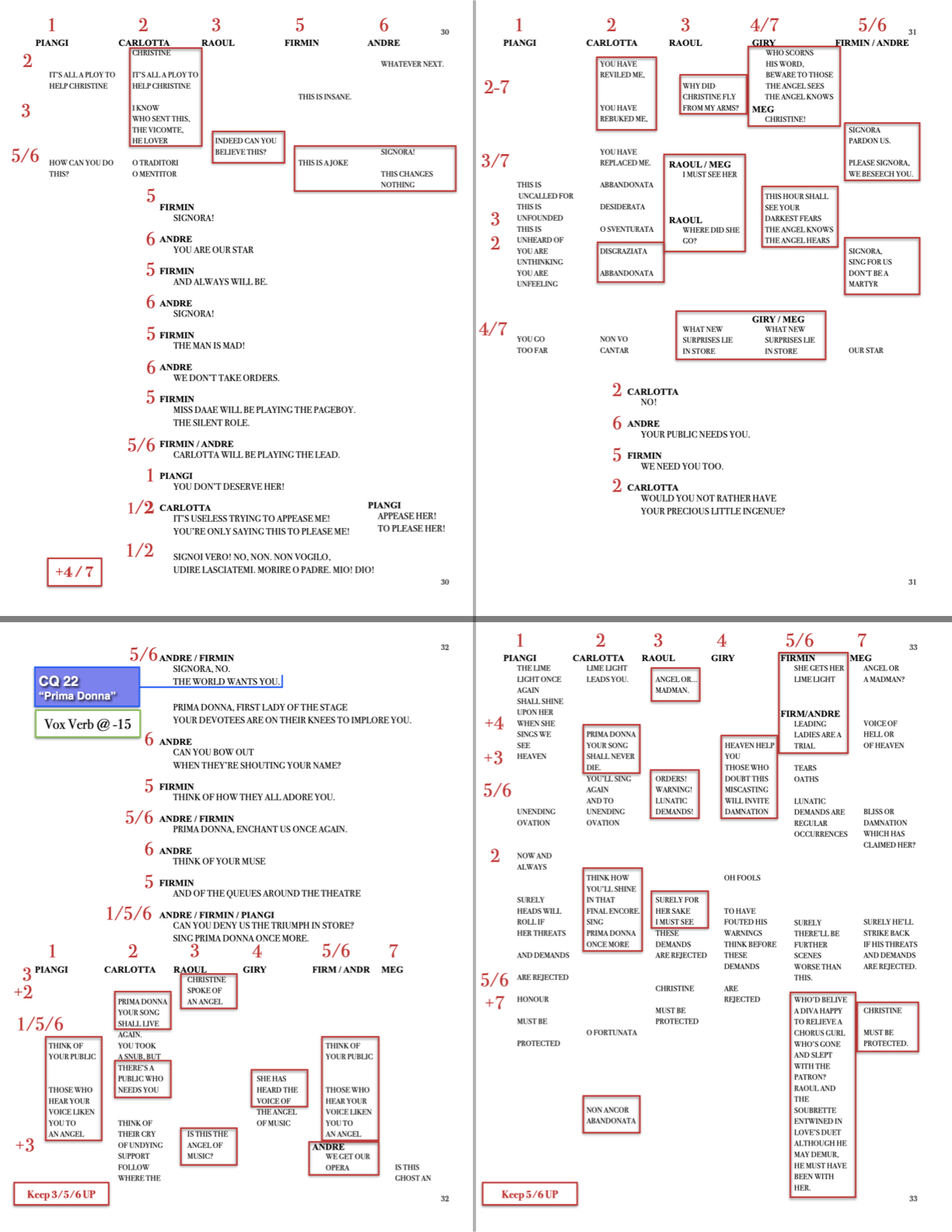

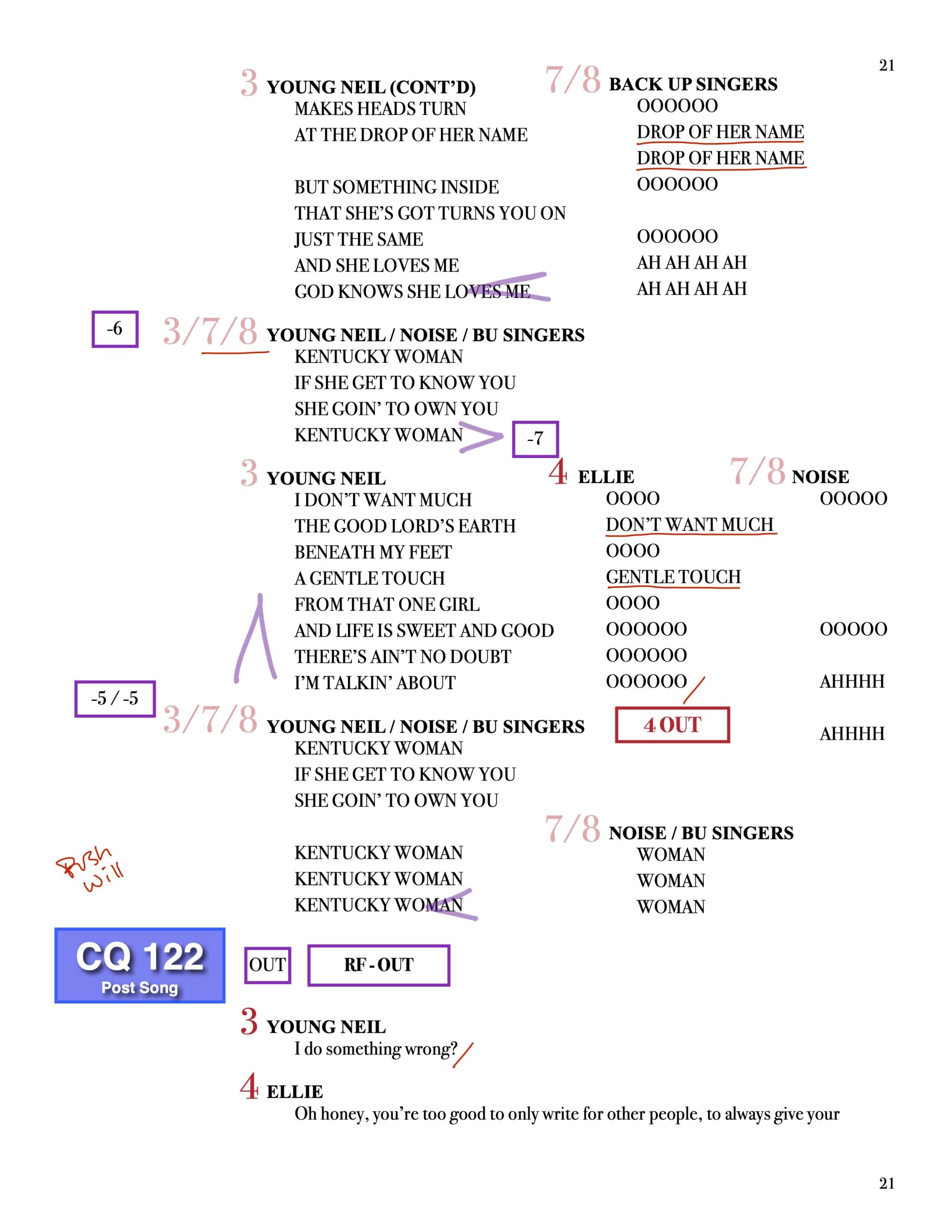

This is a time to exercise independence. Don’t wait for someone to spoon-feed you information if you have the means to figure out yourself. On Les Mis the associate and I were talking about how the focus shifted over the course of the song “The Confrontation,” and he said that we typically follow who’s on top (singing the higher part). So I went back to the score and marked out who that seemed to be, then asked him to double check my work. It worked much better for him to take a quick glance at what I had boxed in my script instead of having to go line by line to tell me who I should be pushing throughout the song.

Everyone has plenty of work to do themselves and the designer will usually be completely onboard if you’re able to take initiative and other departments will be happy to give you information ahead of time instead of having to play catch up on the back end.

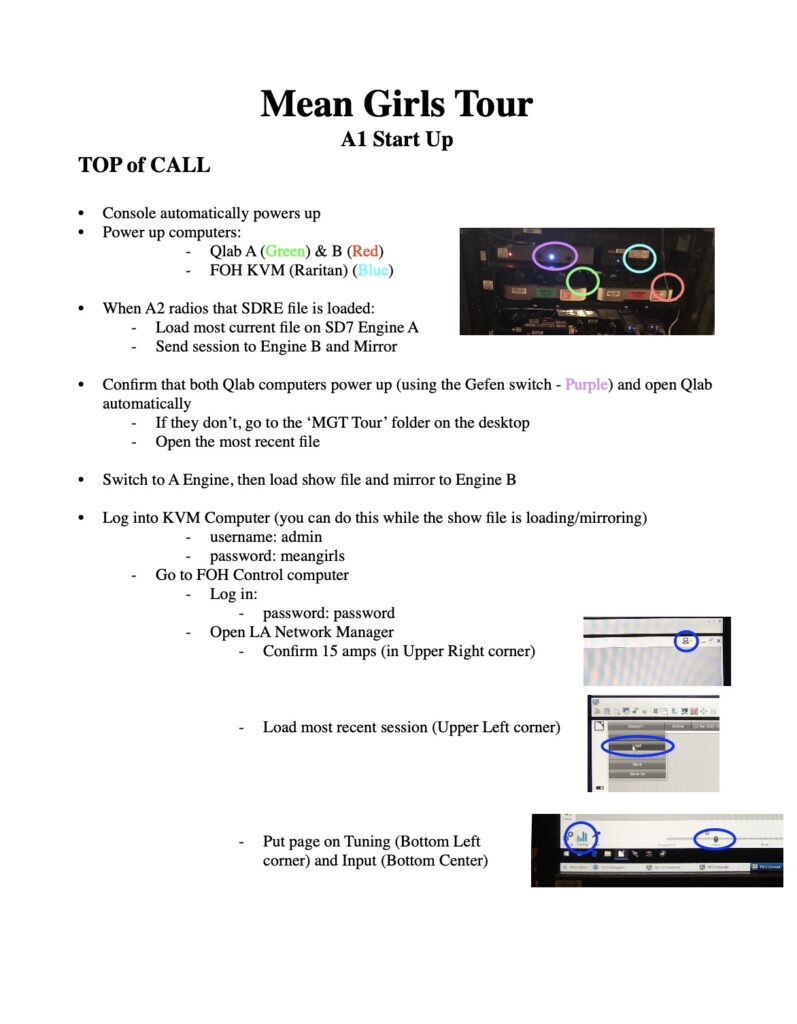

Once you’re into a show run, you’ll need documentation on how your start up and shut down procedures work, especially if it’s a longer run or there will be subs covering the track. Pictures are always helpful, but clear directions can always get the job done:

On tour having a punch list for load in and load out tasks is helpful. I’ll do basic outlines for myself, but have more detailed notes in case someone has to do the load in without me (thank you Covid – examples for this as well as some other documentation are in this blog). All of these are things you should do as an A2 as well.

Speaking of, I’m not the expert on A2 paperwork and mine is very tour specific, but I had a couple documents I would always make:

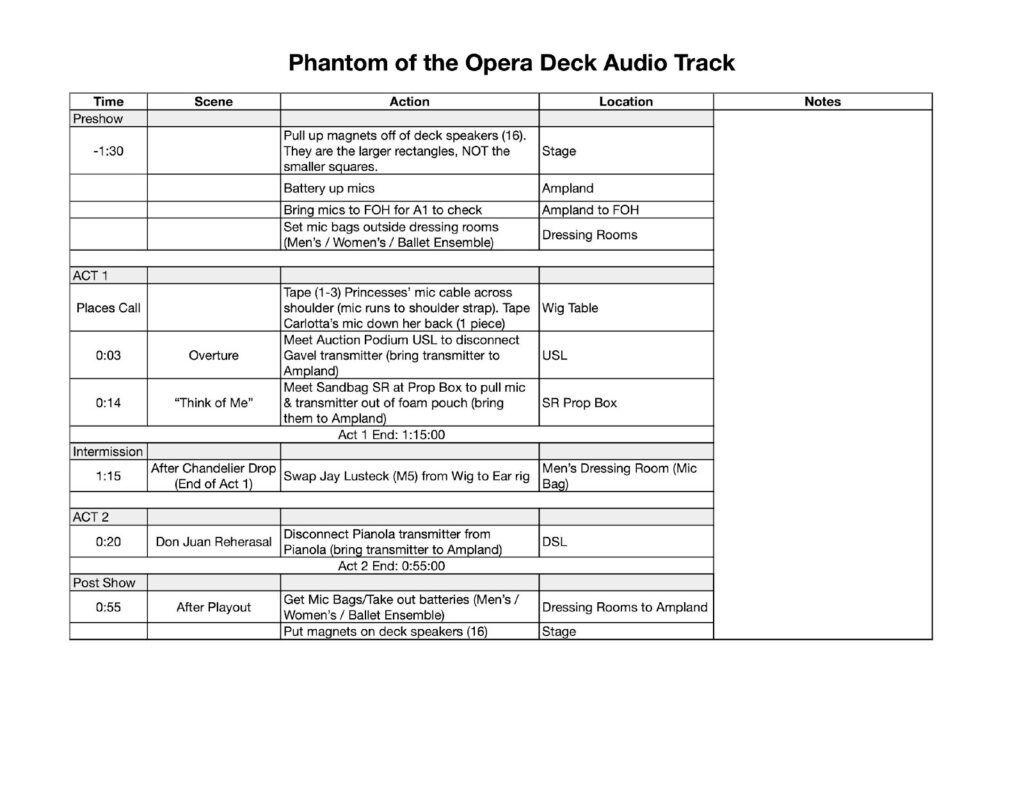

First, you need a track sheet. On tour you’ll hand the local their sheet in every city and it needs to be clear and concise. Mine always included the time a cue happened in the show (some people don’t know the show or the songs so an external reference is helpful), the scene or song (if they are familiar), what they were supposed to be doing, and where they’d be doing it. I’d also leave a column for notes, just in case.

For my own documentation I had a couple spreadsheets I used to organize things:

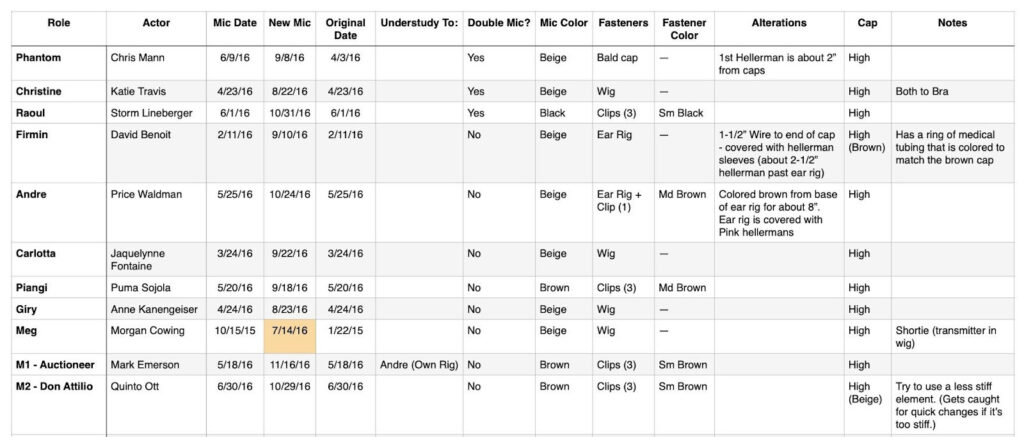

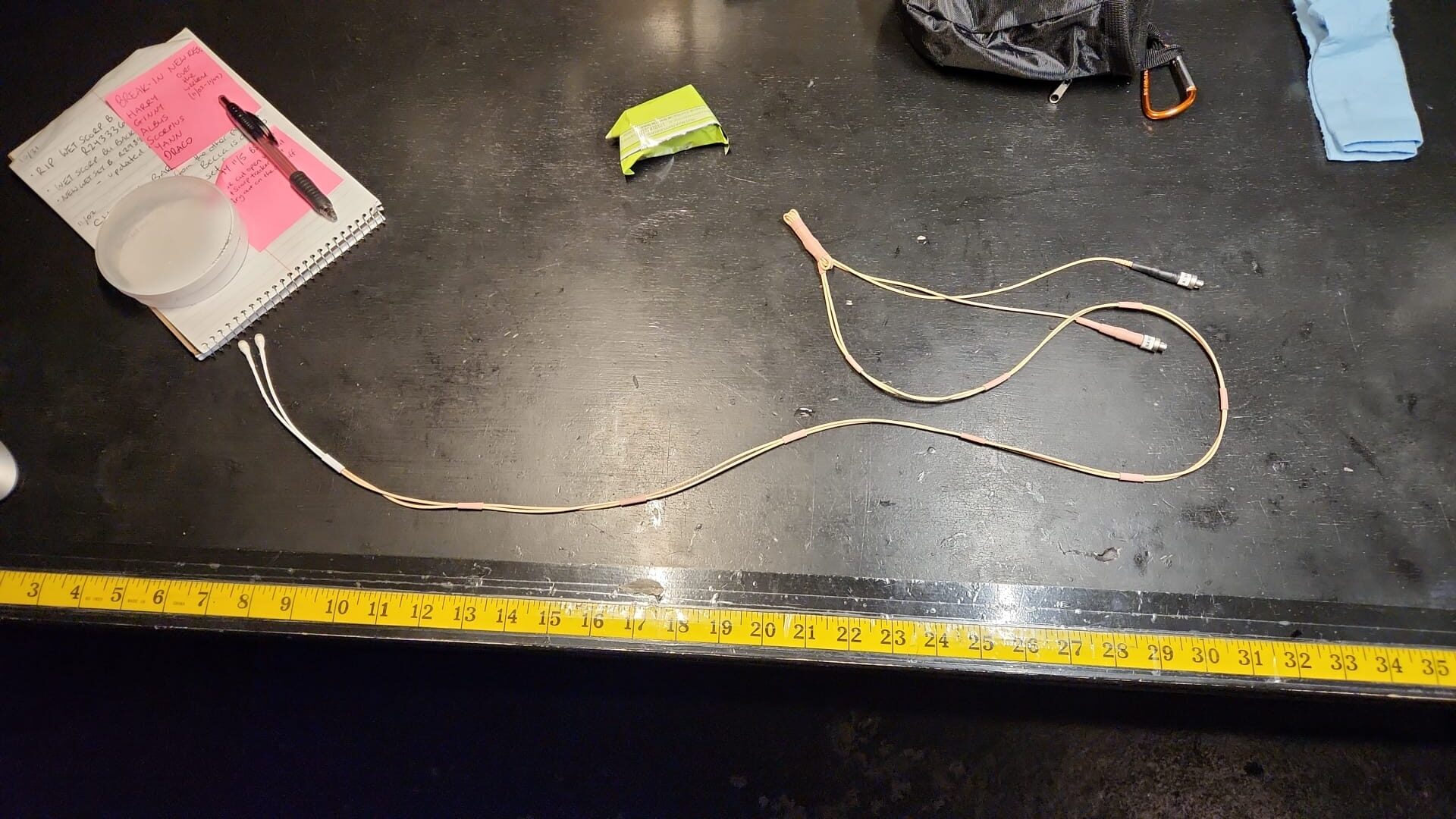

I kept a log of our microphones. What the model numbers were, who they were currently on, if they swapped to a chorus member after the initial use or after a repair, and notes. It’s time consuming to set up and takes regular entries to maintain, but I found it helped me keep track of everything and was worth it in the long run.

In addition to the log, I had what’s commonly called a “bible” which is a list of all the actors, what role they played, what their mic rig was (clips, ear rig, coloring, etc), who they understudied and any alternations for that. More thorough bibles than mine will also include pictures of the actors in their mics to show correct placement and more detailed instructions on the rigs including materials and measurements.

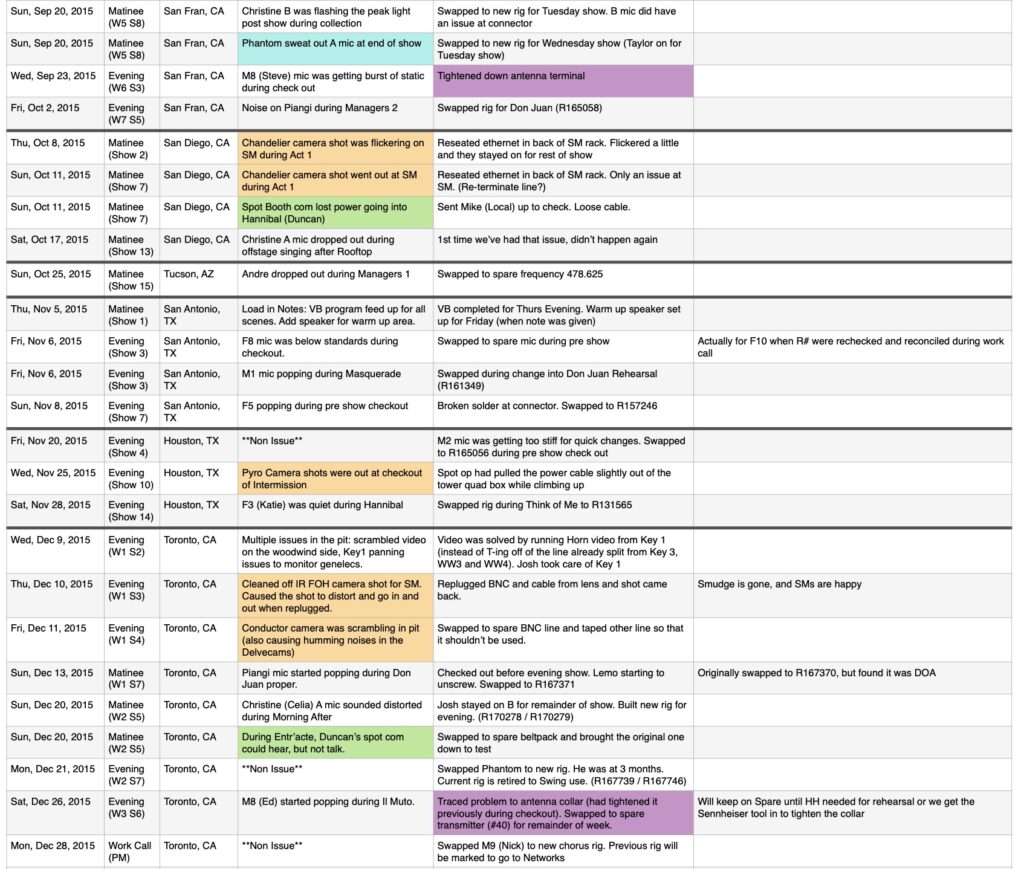

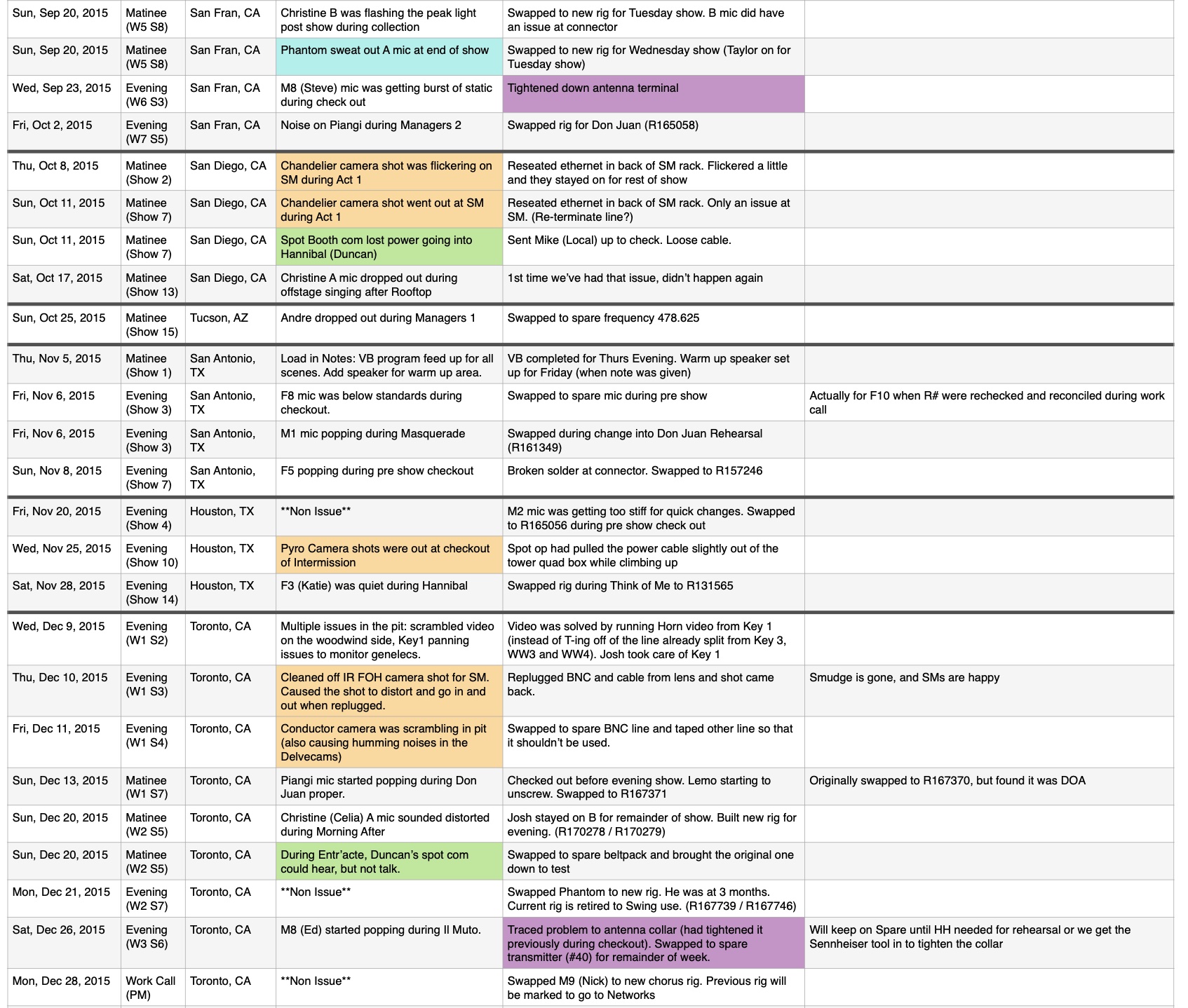

For troubleshooting documentation, I had a running lists of problems that happened during the show (this I didn’t actually start until a year into my time on Phantom, but it’s something I wish I’d started earlier). It was anything from mics breaking/popping to com or camera issues to sweat outs to RF dropouts. I included what the problem was, what we did to fix it, and if there was any additional information or follow up that occurred. I added automatic highlighting in cells for keywords like “camera,” “Phantom,” “com,” or “antenna” so it was easy to find reoccurring issues.

These are all merely examples of what you might find useful and want to incorporate into your own workflow. All it really boils down to is: What do you need to feel prepared in your job? I personally enjoy busy work like typing a script or collecting mic ID numbers, and it helps me feel more organized and prepared for my job, so I’ll happily do it. But paperwork is not a one size fits all scenario, so it’ll take some trial and error to figure out what your organizational style is and what information you want to have within easy reach. My systems were developed over several years of paying attention to what others did and then incorporating them with my own preferences. There are things that change for every show as I learn more and find better ways to do things, so ask others for help and watch what the people around you are doing. You never know where you’ll pick up something good!