Creating a Flying Machine for an Audio Drama

One of the things which I love most about sound design for audio drama is the opportunity it can bring to create entirely new, fantastic sounds. Sounds for creations or beings that don’t exist in our world.

Having worked in sound design and mixing both for short films and voice-based productions, I’ve always thought that creating the sound of imaginary beings or machines for audio drama is both more freeing and more challenging than for visual media. You’re not tied to a physical representation and the obligation to be able to hear everything you see, but you only have audio to “sell” the creation to the listener. Using a processed version of a crocodile combined with your pitch-shifted voice might work brilliantly as the roar massive bear creature in a game, but in an audio drama, the listener may find it hard to believe that sound came from a bear.

I’ve just finished sound designing and mixing the second season of a steampunk audio drama. The writer/director had included several imaginary beings, creatures, and machines in the script, so from the get-go, I knew I would need to dedicate some time to breathing aural life into these creations.

One of these, and probably my favourite to work on, was the fixed-wing flivver. The writer described it like this:

“The flivver is a homage to an early fictional airplane, from H.G. Wells’ ‘The War in the Air.’ It’s more or less like a biplane but powered by different technology – in this case, probably including an aetheric battery – so its turbine whine would sound different. It might also be in some ways less and in other ways more advanced in terms of the aeronauticals.”

This description gave me a starting point for research and sourcing of raw material. I’d be looking at early 20th century biplanes and whatever an aetheric battery was – more on that in a minute.

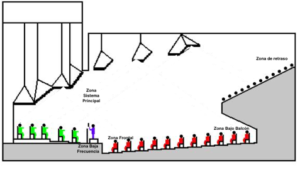

I also knew that I’d have to consider how the flivver sounded from different perspectives. Reviewing the scripts, I noted that I needed six different variations:

– distant perspective, external (heard in the distance from a rooftop)

– close perspective, flying flat, internal (seated in the aircraft)

– close perspective, steep climb, internal (seated in the aircraft)

– close perspective, circling, internal (seated in the aircraft)

– close perspective, leveling out, internal (seated in the aircraft)

– medium perspective, departing, external (heard from the perspective of outside the aircraft as it departs)

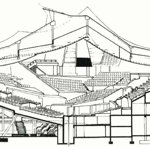

My first piece of research was the sound of early 20th century biplanes. The purchase of high-quality sound library recordings was beyond the budget of the production, so I turned to YouTube as the most likely place to find any recordings of this kind of aircraft. As you’d expect, most videos were from airshows, which meant additional wind noise, crowd walla and applause and occasional commentary.

The amount of noise present in the videos wasn’t too much of an issue. I didn’t want a modern(-ish) biplane sound to be too present in the final sound as the technology didn’t match the steampunk aesthetic. But, I did need enough of it so that the flivver was easily aurally identifiable as a flying machine. It took a combination of finding enough of the right sound, and some careful editing and noise reduction.

After a lot of listening, decided that the sound of the Bleriot XI was the best fit for the base layer of the flivver sound:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RkJymMK33Zk

Next, I needed to add a core engine sound – an engine powered by an aetheric battery, no less. Aetheric energy, as I discovered, is based on a theory developed in the late 1800s by Nikola Tesla, which proposed that the human race could harness the power of the ether (a space-filling medium present all around us) as a source of energy. Ether theories lost popularity as modern physics advanced, so the sound of an aetheric battery is now as speculative as the original theory.

However, there is an invention of Tesla’s that’s still used today to demonstrate principles of electricity and whenever you want to do impressive high voltage displays: the Tesla coil. In the absence of any concrete idea of what aetheric energy might sound like, this seemed a reasonable, and suitably steampunk, alternative. I ended up using a pitched sound of a medium-sized Tesla coil, with an ascending version for when the flivver is climbing. To suggest the kind of mechanics that we associate with steampunk technology, I finally added the sound of a vintage sewing machine.

When I sent the first draft of the flivver to the writer, he felt something was missing – “a sort of insect-like aspect described by Wells, where he talks about the craft’s resemblance to a dragonfly:

“Parts of the apparatus were spinning very rapidly, and gave one a hazy effect of transparent wings.”

I tried various insect whines and flutters and eventually settled on adding the sound of dragonfly wings.

Here’s the finished sound

And in the context of the drama

My next audio drama design and mixing project take me to medieval Europe, which is quite a change of pace! But I hope I’ll be revisiting the world of steampunk audio drama, and its fascinating design opportunities, again soon.