Missy Thangs is an engineer, producer, songwriter, and keyboardist based in Raleigh, North Carolina. Thangs is currently a house engineer and producer at The Fidelitorium, an amazing and unique studio (complete with guest house!) located in Kernersville, NC, about 90 miles west of Raleigh. Throughout her career, Missy has had the opportunity to work with bands like The Avett Brothers, Ex Hex, Ian McLagan (Small Faces), The Tills, Las Rosas, and Skemäta. Thangs has been a prominent member of the Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill (aka The Triangle) music community since the early 2000s, having performed with The Love Language, Toddlers, No One Mind, and Birds of Avalon. Missy has helped shape the sound coming out of the region not only through her songwriting and musicianship abilities but also from the sound she has crafted in production roles.

What first opened you up to the idea of becoming a recording engineer?

I grew up around pop music; my dad is a pop music freak. He had thousands of CDs and records and was way into MTV when it first came out. There was always music on, and my dad’s happiness was sort of funneled through music, so it was such a part of growing up. He was my informer. He was playing everything from Weird Al Yankovic, to DEVO, to Bowie, to Melissa Etheridge — non-discriminating. If it was a good song, had a good melody, and sounded good, he was all about it, and I think I got a lot of that from him.

I think on a real deep psychological level I’m trying to recreate that feeling. Hearing and making sounds that are exciting and make you feel really good. Often those sounds are big and colorful or raw; those are the things that stand out in my memory. So, it wasn’t listening to music from the perspective of how it was recorded; it was more the way music made me feel that got me into the recording aspect of it.

I hadn’t considered recording as a career until I was in college. I was studying meteorology and French at UNC Asheville and looking for something more. I came across the Recording Arts Program, and I remember looking at the course catalog and feeling like it resonated with me. I was like, “What have I been doing?” I want to be in music, and I want to record music, and so I just jumped into that program.

What was your program like at school at that time? Were you learning ProTools at all?

The program was really small; I was the only woman in my graduating class of 25. We started out on an old Tascam 24-track tape machine and an ADAT machine; then we got the first ProTools in maybe 2000 or 2001, which was the start of working on DAWs for me. As soon as we got ProTools, I was like, “Great!” I didn’t use tape or ADAT at all after that. I instantly felt familiar with and comfortable on the computer.

At that point, had you recorded at all as a musician in the studio, or did you just dive in once you started school?

No, it wasn’t until after I was in the program that I started meeting a lot of other musicians. I started playing in a band called Piedmont Charisma, and that was when I had my first recording experience as a musician. We recorded at a super small space in downtown Asheville. It wasn’t around for very much longer after we recorded there. This was before Echo Mountain was in town and there wasn’t much in terms of recording studios. In school we went to a CD processing plant, we got to visit Bob Moog before he passed away, and we went to a voice-over recording studio, but I hadn’t seen a real sexy recording environment ever, and I was like, “What am I going to do?”

It makes sense that you decided to pursue music for a while if you didn’t quite have the resources to jump into something immediately.

That’s right. I was self-taught in recording up until college, and I didn’t have a really strong relationship with any of my professors, so I was kind of on my own, trying to figure out how to get good sounds and how to run a session. I had some friends and colleagues I had made along the way to bounce ideas off of, but I wish I had sought a mentor or someone to talk to. The idea never really crossed my mind.

You moved to the Triangle after school and gradually started playing in more and more bands, and as your career took off, you had the opportunity to record in bigger studios. Was there anything that you took away from your time as a musician in the studio at that time that you think about now when you’re engineering?

Definitely. My abilities to empathize with how the musicians feel and how to anticipate their needs are tuned in, and I think that is everything. For example, I can understand the feeling of having a bad headphone mix, an inner-band conflict, or not being able to get the right take. My past experiences inform the way I handle all those things.

I think it’s so important to be a recording engineer and also be on the other side of the glass. Sometimes you forget what it’s like to get that nervous feeling while in the band; everyone’s staring at you from the other room, waiting for you to get the right take. It’s a good reminder of how to be while you’re leading a session and how to treat the people you’re working with.

Making a record with people is such a vulnerable experience. It’s so essential for the vibe to be dialed in and everyone to be as close to the same page as possible.

Yeah, everything about this job is about people and vibe. When you are working with a group of people or one artist you are constantly picking up cues on their mood and working with that information and trying to get the best out of them. That’s so much of our job! From bringing people a cup of tea or telling everybody to take a break. There’s a lot going on behind the scenes, but the musicians don’t need to know that; it’s not what they’re there for.

You work with a lot of bands at the Fidelitorium doing live-tracking sessions, do you think this is due to your experience of the music you listened to growing up or the bands you’ve played in, is it the nature of the studio, or a combination?

You work with a lot of bands at the Fidelitorium doing live-tracking sessions, do you think this is due to your experience of the music you listened to growing up or the bands you’ve played in, is it the nature of the studio, or a combination?

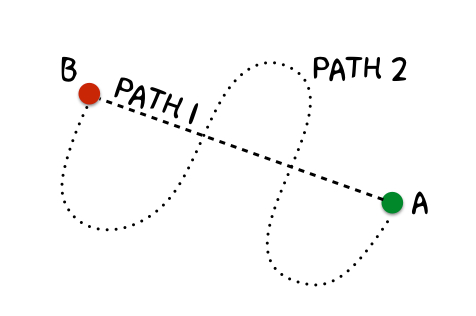

The community that I live in and play in is so intermingled. Everyone is in everyone else’s bands and supports each other, and a lot of people in this community are just here playing music because it’s our lives and it’s what we want to do. My network has sort of facilitated my sound in a way. A lot of people that I’m working with I know personally, and we’ve only got three days, and it’s a five-piece band, and they have a small budget, so we have to make it work. What’s happened as a result of it is that I’ve sort of cultivated this sound for fast-moving sessions. It’s like; you’ve got to track live because we don’t have time to do it any other way!

Then again, the studio does play into that because The Fidelitorium has a large, wonderful sounding room and you can get easily full band in there. There are also a ton of opportunities for isolation so you can get everybody in the space comfortably. It allows me to work quickly when I need to.

What’s happening to me is that my friends, or friends of friends, are hearing a record I did and are reaching out and saying, “Hey I like what you did with this band, we want that sound.” And the way I got that sound was with a quick turnaround live-tracking session. I’ve dabbled in lots of different genres and recording styles, but that’s sort of what I’m doing right now.

It seems like work has been consistently finding you then, which is a positive thing! Do you ever find yourself having to look for work or grow your network in that way? What is that process like for you?

I’m pretty shy; it’s really a lot of word of mouth. There have been one or two bands that I’ve gone up to and been like, “I want to record your band!” But, word of mouth is really everything. A lot of my clients come to me because they’ve heard really great things about other friends’ experiences, and their friends come to me and take a chance with me. It’s really humbling, and a lot of times I can’t believe it. I’ve been really lucky so far, at some point I think I’m going to have to step out of my comfort zone and figure out how to reach new people!

You are now a house engineer at the Fidelitorium, owned by musician and engineer Mitch Easter (REM, Game Theory, Let’s Active). Are you alone a lot in the studio or do you have opportunities where you’re learning directly from Mitch?

Mitch has been my one true mentor. He took me in when I was really down on the industry and taught me what he knows and let me go. I go to him often with questions, and he usually Mr. Miyagi’s me, but every once in a while he offers me some direct advice. I want him to tell me all his deepest mixing secrets, but he’s like, “Who cares? Do your thing!”

I like that idea a lot. I read another article with you where you mention something along the lines of, “the bolder the color, the bolder stroke, the better… there’s no rule in the book.” Can you talk about how this philosophy informs your approach in the studio?

I’m always game for chance or making decisions based on how I feel, versus what’s technically correct. I try not to overthink things, and I’m not afraid to mess up. I think that’s the foundation of where I sit. Being fearless. I want to turn a head. I want people to hear the music from these bands I’m working with and be like “WHAT is that?!” And I think part of that is making bold sounds and being dangerous. It’s not always easy to do, but that’s what I’m striving for.

What should we be paying attention to that you’ve just finished working on? What are your goals for the year?

What should we be paying attention to that you’ve just finished working on? What are your goals for the year?

Well, my main goal for this year is to get back into the studio after having a baby!

A pretty big deal, haha.

I’ve got a lot of cool projects on the horizon! There’s a really talented woman named Reese McHenry I’ve been working with; her record will be out in April. I’ve also been working with this band called Pie Face Girls for a few years that are getting ready to return to the studio to finish a record. And another band I’m going to be recording in May. I’m really excited about – just stay tuned for that, haha.

I’ve worked with many groups with all guys over the years, and I’m finally working with more and more women, and I love it; it’s a nice change of pace. I love everybody I’ve worked with, and I try not to think about it either way, but I have noticed this year that I’m working with more women in the studio and it’s been a really good corner to turn!

What advice do you have for any new or up-and-coming engineers?

Get out there, play in bands, go to shows, and immerse yourself in your musical community! Collect as much gear as you can. Get inside of getting sounds, being experimental, and not being afraid to mess up. Hit up your friends and start asking to record people. I feel like that’s basic knowledge, but it’s an important reminder!

Connect with Missy: