Catherine Vericolli has been working in professional audio since 2003 and is the owner, operator, and manager of Fivethirteen a professional recording studio in Phoneix, Arizona. In her spare time, she teaches audio at the Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences in Tempe, AZ, co-edits Pink Noise Magazine and speaks on industry-related panels.

Catherine Vericolli has been working in professional audio since 2003 and is the owner, operator, and manager of Fivethirteen a professional recording studio in Phoneix, Arizona. In her spare time, she teaches audio at the Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences in Tempe, AZ, co-edits Pink Noise Magazine and speaks on industry-related panels.

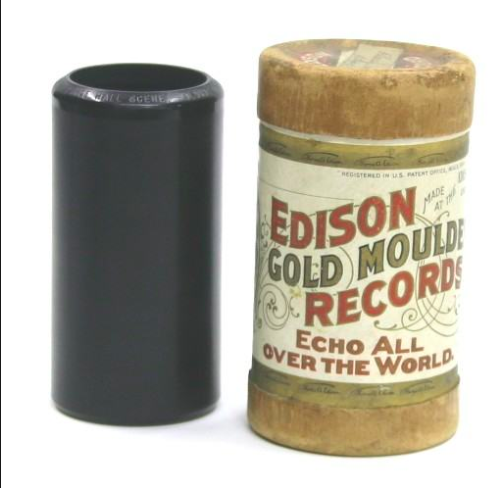

Catherine grew up on 80’s radio and MTV, discovering Metallica and Michael Jackson, while her mom listened to Fleetwood Mac on repeat, complimented by her dad listening to the Carpenters. She was a record collector at an early age and fascinated by how albums could sound so different from one another, especially those released by the same band. She also obsessed with liner notes, and how many people were involved in the creating the album. She also wondered about the recording process. “Records were my books. Much later as a student, I was hooked after a “wave characteristics and the properties of hearing” course. I was pretty much in head first from there.”

Catherine did not initially pursue audio engineering as a career but knew she wanted to work in music. Attempts to understand music theory and realizing she was only a mediocre drummer would lead her tour the campus of The Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences. Her parents supported her choice to go into professional audio and says she learned that if she could explain “how a compressor works to my 86 year old Dad, I can explain it to anyone.”

The rest of Catherine’s education and training came from making “tons of mistakes and figure it out” training, which in my opinion is worth twice its weight in gold over any other educational environment. For me, this came with various internship situations and building a studio when I was 23. I’m still learning, and still making mistakes! Just maybe not as many.”

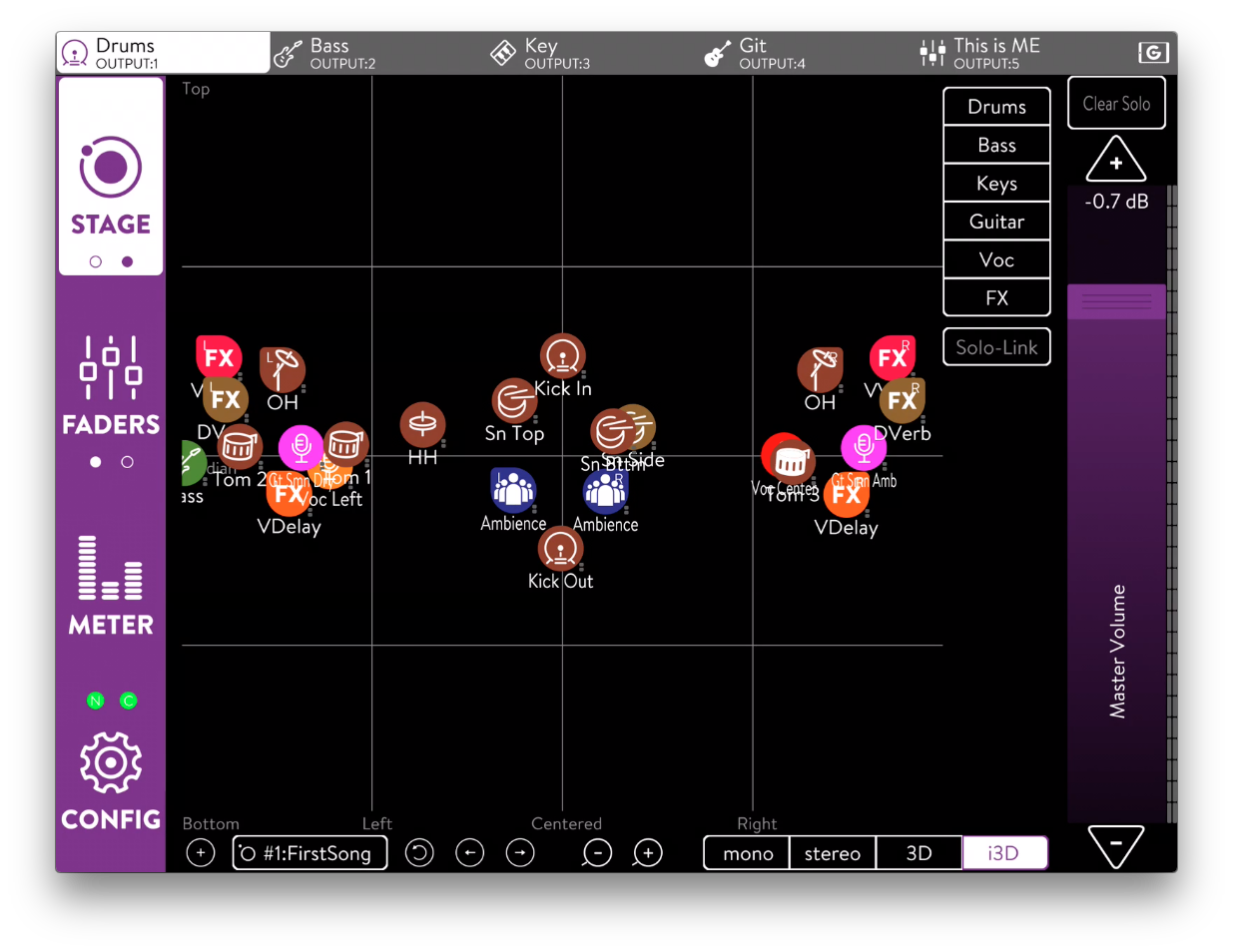

After graduating from The Conservatory, Catherine decided to stay in her hometown and create a comfortable, quality, and professional recording space for her friends and musicians in the local scene. On her way to working as engineer full-time and launching Five Thirteen, Catherine had several odd jobs, from “manual labor to coffee slinging early on while things were being built, etc. They were more placeholders than anything. I had a record store gig that I loved but inevitably spent my whole check on used records that came in, so- not great for my wallet but pretty nice for my collection. I dabbled a bit in live sound gigs when I was younger, but I always felt like I didn’t have the time I needed to get it right! I realized that working on my toes wasn’t nearly as comfy as sitting in a control room with time to tinker. Still to this day I look at live sound folks and am in awe. It isn’t easy. Nowadays I teach audio on the side. Most of the pro audio folks here in Phoenix do. Teaching is rewarding but can suck more out of me than a lot of records I work on. Again, another thing I’m in awe of- full-time teachers. That isn’t easy either.”

Fivethirteen is coming up on their 12 year anniversary and keeps Catherine busy. She is a jack of all trades, managing, engineering, operating all aspects of the studio. She has headed up all console installation and outboard wiring since the first console 2” machine. Catherine considers herself an analog purist and the studio has a nice selection of analog gear.

Catherine is an editor of Pink Noise Mag, (which is currently on hiatus) dedicated to increasing the diversity of voices speaking about record making and to fostering an intellectual tradition to accompany the practice of record making. Pink Noise grew out of the frustration with the persistent male-dominance and chauvinism in the recording scene. The publication has an unabashedly feminist slant.

What do you like best about your job?

Tough question, mostly because my answer is always changing. I think early on I enjoyed seeing a project through from start to finish- simple engineering. This was before I had a staff, or anyone to bounce ideas off of. Later on, I was super into room designing and tech work.

When we built our mixing suite add-on in 2006, most of my focus shifted to getting this right, and the engineering workload went mostly to the staff. I still really love this side of studio ownership. Being able to troubleshoot a problem on the fly successfully can be just as rewarding as anything else. Most of what I enjoy now lies more on the production side of things. I’ve never really been into computers in the control room, so I always try and grab the physical gear first- outboard, tape machines, etc. Now that I have the time to keep all of the analog stuff up to par, it’s easy to incorporate them into any existing project. These days I can pick and choose what projects to get into. I get to spend more time with my staff, bounce around ideas, and the most rewarding thing- I get to watch them grow. It’s great. I also have a lot more time to focus directly on the client. I probably enjoy this the most. The people side of things is really where the magic lies.

What do you like least?

Mixing. I’ve never been a fan, especially now that so much happens in the box. I love tracking. It’s really easy for me to keep things simple while capturing. When I’m mixing, I find myself wanting to click on all the things… like what does this crazy plugin do? Is it faster? Easier?? and that’s my “nope” moment. Most of the time I “track to mix,” so my mixes aren’t that much different than my final rough at the end of a tracking day. Clients sometimes ask: “Aren’t you going to use all the plugins?” …. No. No, I’m not. Most things that sound good, sound good from the start. At least that’s my experience. For me, simplicity is key.

What are your long-term goals?

I don’t have any specific things in mind, other than to be able to continue to support myself financially and to contribute positively to the industry. I travel a ton for various audio endeavors, and I really enjoy it. I’d like to do more of this long-term, and continue to learn from folks in the industry that I admire. There’s so much going on in pro audio that I don’t know anything about! For example, I have an awesome friend that does incredible restoration work, and I’d love to learn more about that.

What if any obstacles or barriers have you faced?

I think anyone who chooses pro audio as a career faces obstacles or barriers. Personal, financial, social… the list goes on. It’s not a very forgiving industry. I think for me honestly, the biggest barrier I’ve faced is my location. Phoenix is a very tough market. Sort of a desert island if you can forgive the pun. We have a pretty measurable lack of community due to the fact that we’re such a young city, and all spread out over a giant geographical area. There is yet to be a “musicianship bar” set, meaning the amount of hours you have to put into your craft isn’t as many as you might have to in order to be successful in larger markets. This leads to a more uneducated clientele in general. Things like pre-production are rarely included in budgets. This leads to more unrealistic exceptions when it comes to time, quality, and cost. There’s a “fast” / “cheap” / “good” vin diagram out there somewhere….

How have you dealt with them?

The best way I’ve found to deal with the fore-mentioned obstacle, in particular, is to travel as much as possible. The more I get involved in things outside of my market, the more I learn. I always come back with more tools and ideas to better educate my clients, which always leads to better recordings.

Advice you have for other women and young women who wish to enter the field?

My advice for women or young women who want to get into pro audio is the same advice I’d give to anyone: Be good to yourself. If you’re not comfortable in a situation for any reason, it’s ok to do the best thing for yourself. Meaning, there are lots of opportunities out there, and it’s ok to find the one that’s right for you. Find a facility, mentor, or gig that treats you the way you want to be treated. Otherwise, it’s not a fruitful learning environment.

Must have skills?

An unyielding willingness to learn, and the ability to greet failure as a gift, are KEY. Also never underestimate the importance of being kind. Whenever someone asks me what I think “the one thing” is to being successful in this industry, the very first thing that always comes to mind is don’t be an asshole. Crude, but so so true.

Do you have a few stories you can tell that have taught you valuable skills? Whether industry people skills or tech skills?

Years ago I was asked to be on a panel at a pretty well attended audio conference. It was my first one. I was super nervous about the whole idea and didn’t feel at all like I belonged there. Basically, the whole experience for me was pretty terrifying. I didn’t really know anyone, so it overall it was an uncomfortable atmosphere, not to mention I was the only woman on the panel. Afterwards, I got chatting with an established, Grammy-winning engineer who basically said. “Look, no one really knows what they’re doing. We’re all just trying to figure it out. We’re all just winging it. You’re doing great.” I was like whoa, seriously? It was a life-changing moment for me in my career. That engineer ended up becoming a wonderful friend, and I’m still very lucky to have him around to remind me that I’m doing alright. Another side note to this story is that much later I met a young female engineer who was doing a ton of bad ass amazing things. She started a killer publication dedicated to featuring women in audio and ended up opening a studio of her own. She gave a speech in PA that I was lucky to attend where she told a story about a life-changing moment that she had when she saw a woman on an audio panel. That woman was me, and it was that same panel. Pretty amazing when life-changing moments come full circle.

Do you ever feel pressure to be more technical or anything else than your male counterparts?

No. I never feel pressure to be anything more than I want for myself. I should add, that this is a learned position that doesn’t always come naturally. It comes from acceptance and experience, and it’s definitely not always a luxury.

Is there anything about paying your dues you wish you would have paid more attention to that came back to haunt you later in your career?

Totally. Not having a mentor is the first thing that comes to mind. I’m lucky now to have a whole handful of mentors that always offer great advice, but if I had made this a priority early on, I think I would have had a lot more confidence as a young engineer. I would probably have a lot more confidence now!

What are your favorite plugins or equipment?

None of my favorite things are plugins. I do however have a short list of things that make engineering very enjoyable for me. Coles ribbon mics, pretty much everything Rupert Neve Designs makes (top of that list is our 5088 console), and our Studer A80 1/2” deck.