From the mountains of Brazil to the hills of Los Angeles, Fernanda Starling has come a long way in her career in audio.

Fernanda was raised in Belo Horizonte (or “beautiful horizon” in English), the capital city of Brazil’s Minas Gerais state. Surrounded by mountains, “Beagá”– as it is known to locals – is a cultural capital. It is particularly known for giving birth to the progressive-jazz-folk musician collective Clube da Esquina, who are regarded as the founders of one of the most important Brazilian musical movements. In the shadows of this popular music scene, a number of heavy metal bands were founded, including the legendary Sepultura.

Fernanda spent her teenage years going to a variety of concerts and eventually started learning how to play bass. In 2002, she formed her first original band with two other musicians. They recorded their demo with André Cabelo, a well-known local audio engineer and owner of Estúdio Engenho. This was her introduction to the world of professional audio. “For the following one-and-a-half to two years, I kept bumping into André at live concerts,” she recalls. “One of those nights, he mentioned that his studio was so busy that he was thinking about getting an intern. Even though I was already working as a journalist full-time, I didn’t think twice about taking the opportunity.”

She immediately immersed herself in the process of studio recording and editing for music. At the end of 2004, after several months of assisting on recordings and mixings, Fernanda was hired by Cabelo: “his studio became my audio school. It was a non-stop recording environment: we often did three sessions per day, generally with three different artists, of all genres”.

Her proven studio recording abilities also led her to receive a federal grant to work as the main Audio Engineer for the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) School of Music. There, she was responsible for recording and mixing classical albums as a member of an all-women research group between 2007 and 2009. This particular recording project was noteworthy, as it catalogued, recorded, and published more than 250 classical songs written by Brazilian composers for the first time.

As an avid learner, Fernanda also chose to complete an intensive certificate course called “Fundamentals in Audio and Acoustics” at the Institute of Audio and Video in São Paulo.

In the Heart of the Music Industry

In 2010, Fernanda moved to Los Angeles to continue pursuing her education in music production. She completed a certificate in Independent Music Production at UCLA Extension in 2012 and then started an Optional Practical Training program right after graduation, which allowed her to pursue work in her field. Although some might think going back to school later in life would be difficult, Fernanda speaks highly of the experience: “I don’t regret going back to school full-time. It gave me the opportunity to immerse myself into a different culture and meet important industry professionals who still influence my life to this day.”

One of those key people is a music producer and audio engineer Peter Barker. Barker is the co-owner of Threshold Sound + Vision, where Fernanda interned. Under his guidance, she started working as a post-production sound editor and mixer assistant. By the end of 2016, Fernanda had worked alongside Barker on the 5.1 mixes for numerous DVD/Blu-ray projects, such as Dio’s “Finding the Sacred Heart – Live In Philly 1986”, Alan Jackson’s “Keepin’ It Country Tour!”, and Heart’s “Live at the Royal Albert Hall”.

Gradually, Fernanda found herself gravitating from studio recording to film and television audio, where there were more job opportunities. She invested in a full production sound kit and owns all the equipment that is needed to record professional audio on film sets. Since 2013, she has worked as a “one-man band”, providing field recording and mixing for independent short and feature films, commercials, TV shows, and documentaries.

Breaking into Live TV

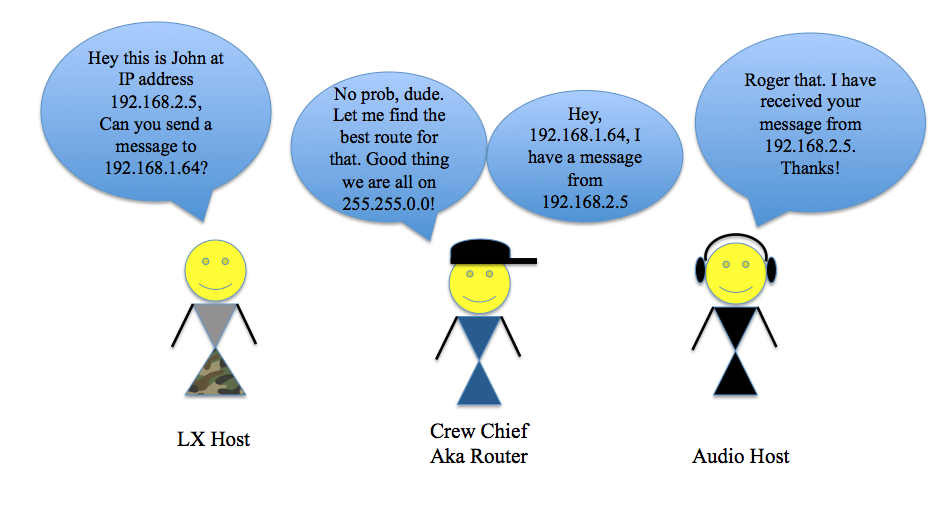

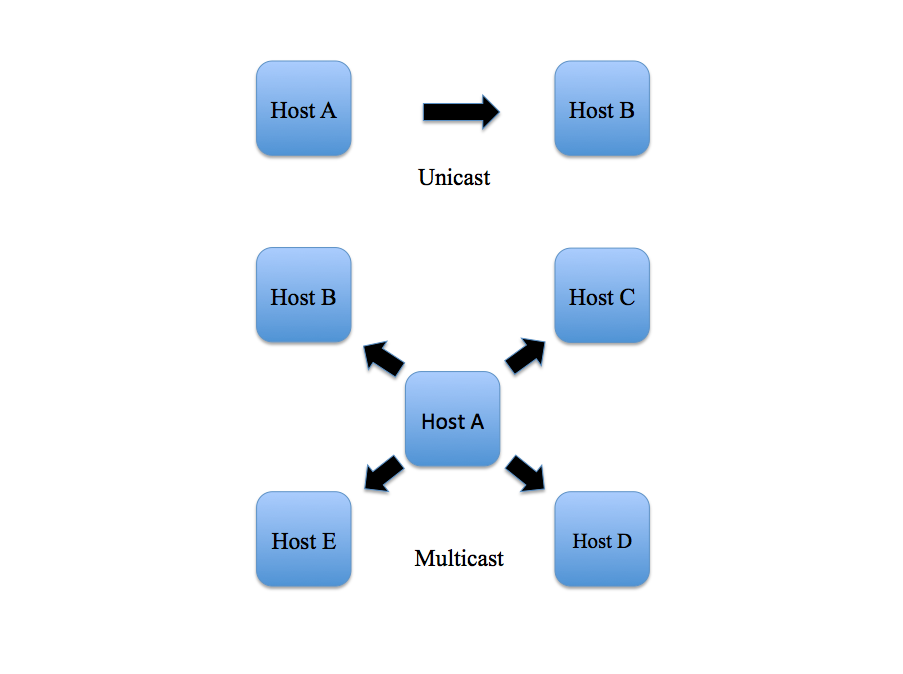

On the Broadcast side, Fernanda stays busy as a Pro Tools Operator/Recordist for live and live-to-tape productions. Her credits include big shows such as Celebrity Family Feud, Grease Live!, MTV Video and Music Awards, The Christmas Story Live! and The Oscars. Typically, she works from remote TV units: “besides the audio broadcast truck, responsible for the mixing of the production elements, music and concert productions also require an additional truck – or even two, depending on the complexity – to handle the music mix of the live performances.”

Fernanda in the Mojave Desert recording sound for the tv series “Big Red: The Original Outlaw Race” (NBC Sports).

Since 2016, she has also worked with Music Mix Mobile West (M3W), an award-winning remote facility company that specializes in recording and mixing music for broadcast. M3W regularly handles audio for award shows and live music performances on television, such as The MTV Movie & TV Awards, the Grammy Legends Award, iHeartRadio Music Festival, iHeartRadio Jingle Ball and KROQ’s Almost Acoustic Christmas. Asked why she likes broadcast audio, Fernanda states: “the complexity and live element make it both a challenging and fascinating environment. These types of television productions typically encompass 160 inputs (and up to 192!) and feature numerous live performances with quick changeovers, so the multi-track recording plays a crucial role. What you hear on air is always a live mix, but the mix settings are prepared in advance.”

In the lead-up to the event, she records the soundchecks & rehearsals. Once the act leaves the stage, she plays back the captured audio so the music mixer can revisit the songs, fine-tune the mix and create snapshots for the live show. Alongside M3W’s co-owners, the renowned audio engineers’ Bob Wartinbee and Mark Linett, Fernanda has recorded countless A-list acts such as John Mayer, Kanye West, Taylor Swift, Beck, Lady Gaga, and Alicia Keys.

Her credits also include working as an assistant and audio engineer for the multi-Emmy Award-winning sound engineer/ playback mixer Pablo Munguia, who she met while studying at UCLA. She has worked alongside him in music playback mixing for The Grammy Awards, The American Music Awards, The Oscars, and The Emmy Awards, amongst others. For these award shows, Fernanda is responsible for building and testing the playback systems at the shop and then assisting Munguia on whatever he needs during the production.

A multi-talented engineer, Fernanda is grateful for all the opportunities she has had in the entertainment industry: “being able to stay true to my musical roots and working with legendary audio engineers is definitely one of the best parts of the job!”

You studied journalism at university. Do you wish you had had the opportunity to study audio engineering first?

Is audio engineering school really worth it? This is a common question and I have always wondered that myself. To be sincere with you, after I had finished high school and had to pick a career, I didn’t even know that audio was an option… The reality in Brazil is different from North America. I became more familiar with the audio world while working as a journalist.

Back when I started my post-secondary education, there were no universities offering a bachelor’s degree in audio. There are a few private audio schools in Brazil, most of them in São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, but they just offered short-term certificate programs. Today, if I am correct, there is actually one university in Brazil offering a degree in audio engineering.

The way I’ve always tried to compensate for the lack of having an audio diploma is taking multiple short-term courses and classes to fill specific gaps in my knowledge as I advanced in my career.

It seems that the audio industry is much different in Brazil then what we experience in North America. Can you speak to the differences?

Like I mentioned above, there is little access to formal education in audio. Besides that, the limited access to professional high-end gear may be one of the biggest differences. Brazil’s tariff regime is ridiculous! Imported manufactured products are subject to a wide range of taxes at all stages of the chain. Because of that, the final price of an audiovisual product is two to three times more expensive than it would be in the US. Therefore, independent studios in Brazil are not as well equipped as the American ones. One of the first lessons I learned from my first studio mentor, André Cabelo, was that gear is not the most important thing in the business: neither for making a good mix or to build and keep your clientele. What counts most is mastering the craft, having a relationship of trust between artist and the engineer, and creating a welcoming environment.

Another difference is that federal government incentives play a big role in the Brazilian audiovisual and music production world, particularly in the independent scene. Maybe because of that and other cultural aspects, independent Brazilian artists get more of a chance to perceive music as more of an art then as a product?

Can you explain what you mean by these federal government incentives?

There are numerous kinds of tax relief, i.e. tax benefits and incentives at all levels of government (federal, state, and local) in Brazil. Some grants, for example, are based on fiscal incentives that allow for companies or individuals to invest a share of their income in cultural projects in exchange for a tax reduction. Those benefits not only help to promote and democratize the access to culture but also directly supports independent artists. When an artist receives a grant, they can dedicate themselves to their craft, record & promote their album without worrying about working multiple jobs to fund their musical career. Besides helping musicians directly, these policies also benefit studio owners, audio engineers, and other professionals involved in the Brazilian music industry.

I will say I was shocked when I arrived in the US in 2010. I was used to a non-stop recording environment back in Brazil and it seemed that here, very few independent artists had the budget or opportunity to go to the studio and record full albums.

What about the TV Broadcast and film Industries? What are the biggest differences between America & Brazil?

When we talk about TV programmers and filmmaking, it is almost unfair to compare the production capabilities of both countries. This is because of the difference in the size of their populations, and the difference in the ability to recover production costs domestically. It is often cheaper for Brazilian media companies to buy series & films from the US than to produce their own. In Brazil, the content produced outside the TV broadcasters, including film, is reduced and depends on government incentives.

Another difference is that broadcast TV is an extremely concentrated sector in Brazil, dominated by Rede Globo. They are one of the largest commercial television corporations outside of the United States and the largest producer of telenovelas (soap operas) in the world. Generally speaking, the US is famous for producing and exporting film, while Brazil is famous for producing and exporting telenovelas. It’s actually really impressive what the Brazilian TV industry has managed to create: there are three original soaps going out every evening, and each series lasts approximately 200 episodes.

Can you tell us more about your experiences as a musician?

The FuDogs at the “Venice Beach Music Festival

Although music is my passion, I also had to focus on my careers, which were first journalist and then audio engineer. The best bands I played in were the ska ones. I Brazil I had a 7-piece ska band called Os Inflamáveis (The Inflammables). We had tons of fun playing together in small venues and festivals. Before I left Brazil, we were playing every Sunday at a local pub. I used to say that playing ska is my therapy: the bass lines are interesting to play, and the music lifts you up! I also joined other bands while I lived in Béaga and played as a hired musician for an artist called Makely Ka, but Os Inflamáveis was by far my favorite experience.

When I moved to LA, I really missed playing in bands. One day, out of curiosity, I checked the musician section on Craigslist and I couldn’t believe my eyes! There was a post about an opening for a bass player in a local ska band and went to audition. I passed the audition and joined the Fu Dogs, we played together for five years at several special events in Santa Monica and Venice, as well as well-known venues like The Roxy. I also played briefly with an original power trio called Bombay Beach Revival, and with FEMZeppelin, a female Led Zeppelin cover band.

It seems that Belo Horizonte had a vivid independent music scene. Besides playing in bands, is there anything else you miss?

I would say that it’s quite easy to become a workaholic when you live in LA, especially when you love what you do. I definitely miss Beagá’s nightlife and the social life I used to have… There was always something to do! If I wasn’t going to my friends’ concert, I was bumping into them at cultural events or festivals or we were enjoying a good conversation at the bar. This popular local saying perfectly sums up life in my hometown: “se não tem mar, vamos pro bar” (we have no sea, let’s go the bar).

What is your favorite piece of gear?

I don’t have a particular one any recording device fascinates me for its capacity of capturing the uniqueness of a specific moment and then being able to play it back later!

I do use redundant Pro Tools Systems for broadcast recordings and Sound Device’s 633 mixer/recorder for my one-band-man field recording. At M3W’s studio truck, I oversee running a redundant Pro Tools MADI System (up to 196 inputs each) for audio recording (one as backup) and a satellite system for video playback locked to either of the recorders. I also like combining a flying pack of Pro Tools Madi and Sound Devices 970 when I have a gig that requires redundancy and a high track count below 64 inputs.

What advice would you give to young women looking to get into the audio field?

Try to learn from other people’s experiences. Surround yourself with those who know more than you. Read manuals. Be open to changes. Be professional. Understand the psychological aspect of working with artists… And remember that there is no right or wrong path, just keep working on your skills, take care of your emotional health, be worthy of trust, and be patient.