Good art lies in the details. Oscar Wilde said of writing poetry: “I spent all morning taking out a comma and all afternoon putting it back in again,” and while facetious (like everything Wilde said), it rings true for all forms of creation. Once you get through the bulk, the initial drive for content, then it’s time for the details. A single comma can make all the difference. It can change the meaning, change the interpretation, change the flow, change the visual aesthetic of the poem. It is a decision as important as the change is small. It’s when you begin to dig in and to polish that art really takes off.

This is no different for music

You can get down your chords and melody, layer your instruments, get broad strokes mixing, and get it sounding pretty (damn) good with ease, but getting that last little push, that takes talent, and it takes time. How much time you have to make a record depends on your budget, and that graph is a smiley face. You start out home recording, no budget, just your time, and you can spend as long as you want creating and fine-tuning and to make the art that you want to make. Eventually, though, you may get the itch to do something more. Maybe you hate engineering or can’t wrap your head around mixing, maybe you want a producer to help you bring your musical vision to life. Maybe you just want to experience going into a studio. So you save and save and when you’re ready to realize that studios and engineers and producers are expensive. Thousands. At best you can do a couple of days. You’re now losing time. Now, instead of having forever, you have hardly any time, and the details get left behind. Of course, as your budget gets larger you can afford more time until you’re working with so much money that you’re back where you started, able to spend as long as it takes (unless you have a deadline) in order to get your art the way you want it.

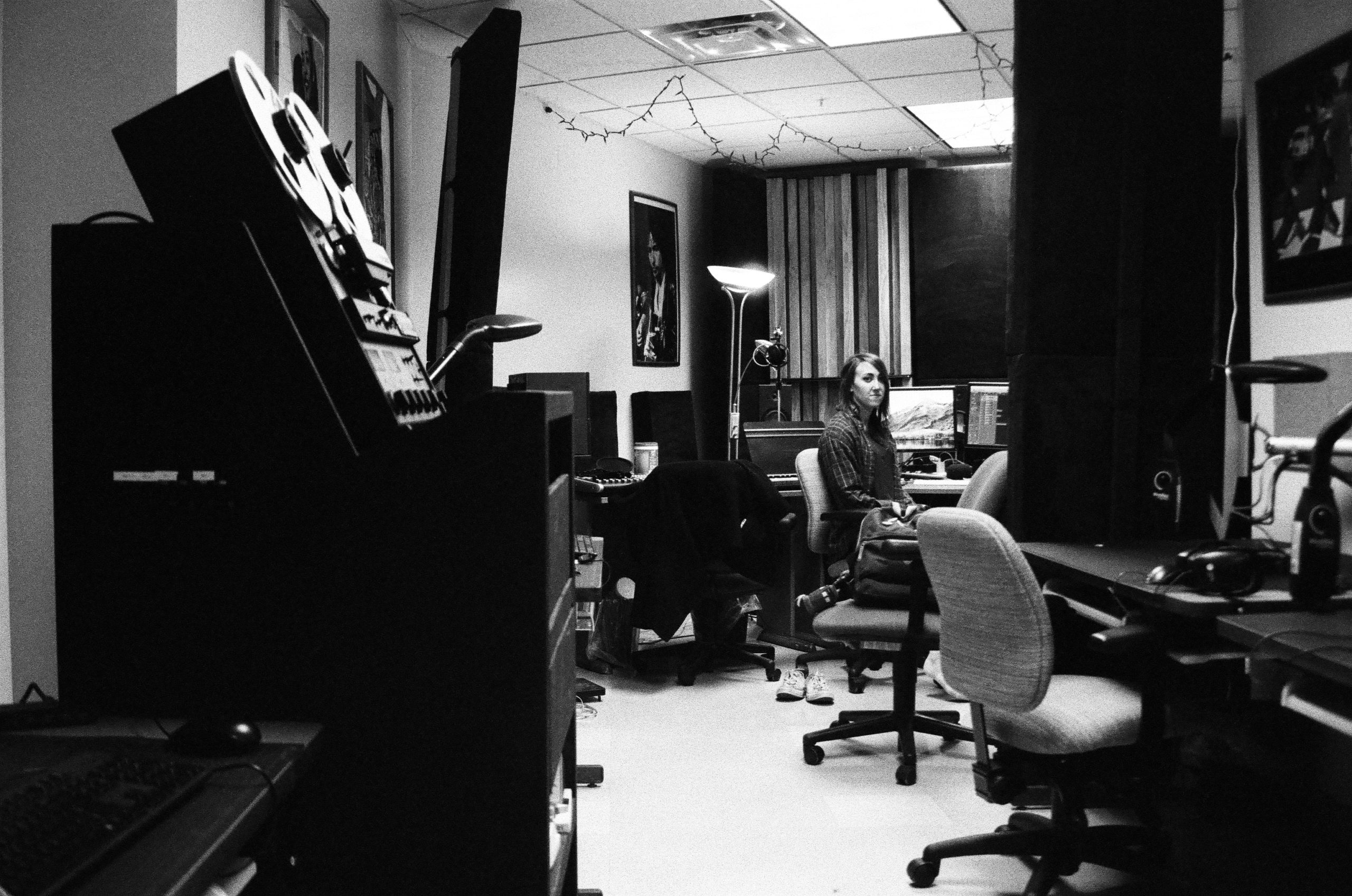

Hoping for a million-dollar budget is probably out of the realm of possibility for you, as it is for most artists, but that doesn’t mean you can’t put the level of creation into your art that you want. Enter what I call hybrid recording (Not to be confused with recording with analog gear into a DAW like it used to refer to. These days, that’s just called “recording.”). You do your initial recording in a studio, getting your live tracking and as many parts as possible done (especially drums), and then go back to home recording for the rest of it. That’ll give you that studio sound, and that studio experience (since, you know, you’re recording in the studio), while also giving you the freedom and flexibility to not only create the art you want but also do so without feeling forced by time and by money into inspiration. That can yield amazing results, especially with a talented producer who can mitigate the anxiety of the clock (it is the producer and engineer’s job to keep track of time, btw, not the artists’), but sometimes what you really need is a late-night cup of coffee and a pair of headphones in the place you’re most comfortable.

Because of the pandemic, I’ve been doing a lot of distance/email producing, and I will say that it’s actually working out pretty well. My artist will record their song, with all the time they need to construct arrangements and get the right takes, and then email me a mix. I’ll listen through, make notes that I send back, and we’ll do it again for the next version until we’re both happy with the arrangement and the performances and feel the song is ready for mixing. It takes a lot less time on my part than actually going into the studio to do overdubs, and it gives the artist that flexibility and freedom. Yes, it does mean that I can’t be there to coach performances and to stoke inspiration in the moment, which are all really important roles for a producer (probably the most important), but that doesn’t mean we can’t get amazing results, because we do. It just takes a little while longer, a little more back and forth, and a little more guesswork (depending on the rough mixes).

So how does a recording session like this work?

For a 10-12 song LP, you’re going to be looking at 3 days in the studio. The first day will involve a lot of setup (low end 4-6 hours, possibly more), and at least the first two days will be over ten hours. If your engineer or studio won’t work that long, then you’ll have to add on another day. Be upfront with your budget, and try and have some padding in case things go over. Your producer/engineer should be able to adjust things to work with your needs. Maybe you skip using all that fancy outboard gear that takes a bunch of time to set up, so you can get an extra song or two done on day one. Still, you shouldn’t push or rush your way through everything in less than two days. I’ve done 6-7 song days before and they suck, and the results sound like it. In order to prepare to go in, though, you’ve got to practice. I tell my artists to practice two hours a day for two weeks leading up to their recording session. And why wouldn’t you? You’re spending a lot of money and you want to make the most out of it, ample practice not only gets you the best results but saves you money.

Editing is a vital part of making music, and good editing can often be the difference between sounding indie and sounding pro. Even with the practicing, you’re not going to go in and be a one-and-done kind of thing. You need to do multiple takes, no only because you need material in case you notice things you want to change later on, but because if the first take is great, the second take can always be greater. And there are always parts of each take that are better than the same parts in others. Even that killer magic take. Basic take comping will take up a good chunk of your recording time, and you don’t want to also have to spend that time having the individual parts edited. That sucks. It sucks for the band because it costs money, and it sucks for the engineer because editing is boring. I try to put off editing until after the recording session to save on studio fees. In a perfect world, I’d spend about 1-1.5 hours editing a song. In reality, I’ve spent 4-6 before, because the bands don’t listen to my practicing requirements. If I have to spend four hours per song on editing, for our 12 song LP that’s over a full week of work. Vs less than two days. How much money do you think you’ll save by practicing.

Once we get our studio tracking done, and our editing, it’s time for the actual fun and the whole point of this article. I’ll send you rough mix stems, so you can adjust your drum and bass and guitar and whatever levels, and then you’ll do what you do best: make magic. We do our back and forth, and once everyone is satisfied, we move on to mixing.

Mixing is a vital part of making music. It’s when we make all the different tracks we recorded sound good together, take care of that EQ and compression we skipped to save on studio fees, and handle the final creative touches to really make something special. Mixing can take a lot of time, certainly, the first song does, and might end up costing as much or more than your tracking session. You can get mix engineers for cheap, you can get those who are expensive. You can even get

Finally, we get to mastering. Mastering is the final polish that gets the songs ready for release. This is typically done by a different engineer to get a different pair of ears on the production. And after that, we’re done!

What I’ve outlined here is not making records on the cheap. There are oodles of ways to get your budgets down to next to nothing. Make friends with someone who has a home studio, invest a few hundred bucks into your own equipment, find someone fresh out of engineering school looking to build a discography. But if you want the next step, something more, working with an established pro in a proper professional studio, then this is a way to go about it that can give you that sound and experience, and make something that would otherwise be unaffordable just about within the realm of possibility.

But seriously, practice.

Lillian Blair is a producer, engineer, and audio educator working out of the Seattle area. She is currently a staff engineer at The Vera Project Studios, where she chairs the Audio Committee, teaches studio recording and audio mixing and mastering. She is also co-founder of the new Audio Engineering Certificate Program at North Seattle College.

Corporate Sponsors

Corporate Sponsors