Some Facebook groups I found in the LA area.

I’d like to note that a reel typically consists of a compilation of clips of live-action or animated TV shows, films, or even video games where the sound is replaced with your own edit. The materials you choose can come from released media where you can use the existing sound as a guide for your edit. However, it’s also a great opportunity to collaborate with up-and-coming filmmakers in your creative community to put together the sound design from scratch. This was particularly common while I was in Boston where college students majoring in film and audio post-production could easily work together to fulfill a project. While it’s certainly not necessary for a great reel, I recommend using Facebook groups to connect with filmmakers, creatives, and more sound editors in your area.

KEEP IT SHORT

If you’ve been searching the internet for tips for your portfolio reel, this is probably the most common tip you’ve seen. While a “short” reel may be defined differently to various editors, it’s important to consider the attention span of the person viewing your reel and the variety in your reel. A good rule of thumb is to keep your reel between 2-4 minutes long. However, how you break down that 2-4 minutes can make a big difference, which leads me to my next point…

TAILOR TO YOUR DESIRED POSITION

Just like with any other resume, your portfolio reel should also be tweaked and adjusted based on the position you’re applying for. It’s important to get all the right information for the places where you want to work or for whose work interests you. For example, Boom Box Post specializes in post-production audio for animation, while Pinewood Studios focuses on live-action. A larger studio like Skywalker Sound spans across media, but many of their releases involve heavy live-action fighting sequences. Now, think about how to break down your reel based on the kinds of post-production studios you want to join. A portfolio reel for an animation-focused studio might include 3 1-minute clips involving different types of animation, while a portfolio reel for a large-scale live-action production studio could have 2 2-minute clips with long and dynamic fight sequences.

HAVE AN ORGANIZED DELIVERY METHOD

Your portfolio reel will most likely come in the form of a compiled video with a sharable link. Sometimes (however not as common) employers may ask to see the full ProTools session instead of or along with a link to a reel. If this is the case, they are evaluating your organization skills, so it’s essential to have all tracks labeled, clips organized, and a smooth signal flow in your session that makes it easy for them to see what’s happening and listen without any problems. We have a great blog on keeping your ProTools sessions organized, which you can read here. You can also check out this blog we have for solid file naming, which will give a great impression if you’re sending more than just a link to employers.

Example of Vimeo platform.

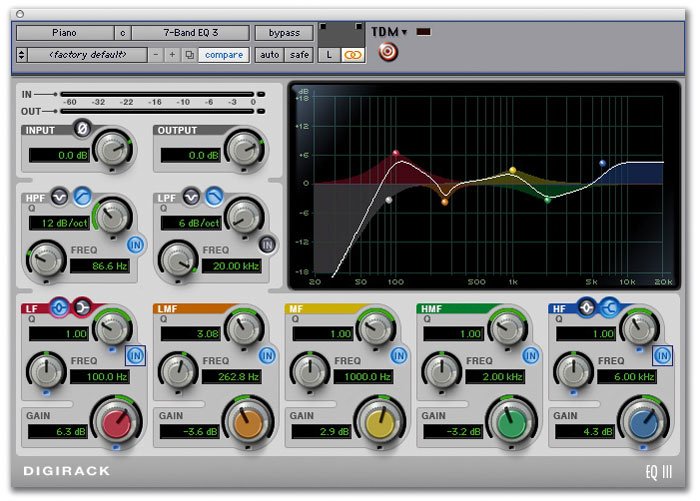

ProTools EQ-III.

If you’re sending a sharable link, there are a lot of great viewing options that are easy to use and easy for others to watch, including Vimeo, Youtube, and Squarespace. Once you’ve compiled your work together in a ProTools session and bounced a Quicktime video of your work, you can upload that video to any of these platforms and include text information to describe the work you did on each clip, breaking down dialogue, Foley, and sound effects.

CONSIDER EVERY ASPECT OF THE PROJECT

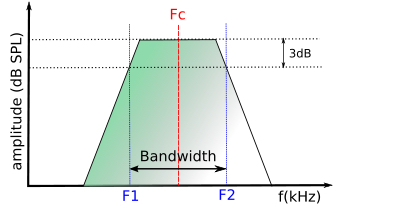

While you may be applying specifically to a sound editing position, you still have a chance to show off your understanding for the big picture. This can include recording your own sound effects, Foley, and dialogue, and putting together a basic mix for your reel. Adjusting levels and panning, and using stock ProTools plug-ins like EQ-III to balance out any unwanted frequencies is a great way to show your understanding of how your effects relate to each other.

Sometimes it is easier to record some of your own sounds instead of finding effects from libraries. While Soundly and Splice both offer a limited amount of free sound effects, other general library platforms like Pro Sound Effects can be very expensive. Recording your own Foley or vocal effects can offer more flexibility, and you can also put together your own sound effects libraries to show to employers, simply by collecting those sounds and creating playlists in SoundCloud.

Ultimately, your portfolio reel should have a concise demonstration of your skills as an editor, it should highlight the style or genre of the studios of your interest, and it should be easy to access and navigate through. Portfolio reels can come with a lot of opportunities to show off organization skills and resourcefulness, so be on the lookout for more ways to impress potential employers when you start building your reel.

If you enjoyed this blog, check out these:

AUDIO POST-PRODUCTION DATA MANAGEMENT TIPS

GET TO WORK! 5 TIPS FOR BREAKING INTO POST SOUND

HOW TO CRUSH YOUR FIRST GIG AS A SOUND EDITOR