Making Sonic Magic from Auditory Illusions

So, if a tree falls in the woods, perhaps it makes infinite sounds

A few years ago, I attended a talk on wave field synthesis, and to say I was captivated feels like a sorry understatement. Wave field synthesis, if you are unfamiliar with it as I was, is a spatial auditory illusion and rendering technique that produces a holophone, or auditory hologram, using many individually driven loudspeakers. The effect is that sounds appear to be coming from a virtual source and a listener’s perception of the source remains the same regardless of their position in the room. Its application in theatrical contexts is very new, but as the techniques and technology slowly become more widely available, the potential for theatrical applications is astounding.

This introduction to wave field synthesis, in addition to being quite exciting, pointed me towards a categorical lack of knowledge about auditory illusions. Since then, I’ve been filling in the gaps and adding these illusions to my sonic toolbox. Now, quite a bit of theatrical sound design could be considered spatial illusions like, for example, when we recreate actual physical phenomena like the doppler effect. Auditory illusions, however, encapsulate many effects extending far beyond this.

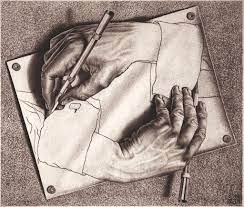

Optical illusions have long been the inspiration for and integrated into visual arts. M.C. Esher’s work, for instance, presents the viewer with impossible objects and perceptual confusions. In psychology and neurology, the study of optical illusions has played a large role in understanding the visual perception apparatus. Due to the historical ease of reproducing and distributing visual material, as opposed to auditory material, visual illusions have long been widely encountered, studied, and applied in artistic works. The history of auditory illusions and their use in psychology, music, sound design, and elsewhere is much shorter.

Auditory illusions, much like visual illusions, reveal the deficiencies and oddities of our perceptual processes, but the auditory and visual systems have their own unique attributes. The field of psychoacoustics examines how the brain processes sound, music, and speech. Hearing is not strictly mechanical but involves significant neural processing and is influenced by our anatomy, physiology, and cognition. Researches have even found that how we unconsciously interpret sounds is influenced by our individual environments, backgrounds, and dialects. Auditory illusions provide key information in unpacking our auditory processes for psychologists and neurologists. In artistic applications, auditory illusions provide similar insight into our perceptional processes and illustrate that there is no one true sonic reality.

Dr. Diana Deutsch, a psychologist at the University of California, San Diego is at the forefront of psychoacoustic research and her work has utilized countless auditory illusions and sonic paradoxes. If you want to hear examples and read her work, visit her website here: http://dianadeutsch.com/. Due largely to her research, there has been increasing understanding of the cognitive factors in the auditory system and how it has evolved over time to help us interpret our sonic environments effectively. Psychoacoustic research has been applied in myriad contexts including modeling compression codecs like mp3s, software development, audio system design, drone flying, car manufacturing, and even, terrifyingly, in acoustic weapon development. In the arts, psychoacoustics and auditory illusions have been applied in musical contexts, sound art, film, and theater, though these applications are fairly nascent.

There are a number of types of illusions that can be roughly categorized as spatial illusions, perpetual motion, and non-linear perceptual effects. More auditory illusions continue to be uncovered and understood, so these categories aren’t rigid. Spatial illusions are already a mainstay of theatrical sound design. We frequently manipulate spatialization to make it seem as though sounds are coming from a particular source or direction other than the loudspeaker producing the sound. Holophones can be created in a number of ways including wave field synthesis as I’ve mentioned. Binaural recording is another example of spatial manipulation, reproducing interaural features and anatomical influences of the head and ear. All of these spatial illusions exemplify a distinction between the physical properties of the sound field and the perception of what listeners actually hear.

Unreal sounds created in the inner ear or brain are a part of our daily lives that we typically don’t notice, and there are several auditory illusions that mirror common visual illusions. A Zwicker Tone, for example, is the sonic equivalent of an after image. Illusions of Auditory Continuity show us that when an acoustic sound signal is momentarily cut off and replaced by another sound, listeners perceive the original signal to continue through the interruption. Through the familiar Precedence or Haas Effect, we perceive a singular sonic event when one sound is followed by another with a short delay time, and that we ascribe directionality based on the first arriving sound. While subtle, these are all valuable design techniques.

Less subtle are perpetual motion illusions. Pitch and tempo circularity is roughly analogous to the barber pole illusion in which a sound seems to be endlessly ascending or descending or a rhythm seems to be endlessly increasing or decreasing in tempo. Both pitch and tempo circularity encapsulate a number of techniques and effects. The Risset Rhythm and Shepard Tone are complex versions. The Shepard Tone most notably influenced the film score for Dunkirk and created a palpable sense of anxiety. Much like Esher’s impossible stairs, circularity illusions are both unsettling and entrancing, a powerful design technique.

There are a number of speech-related auditory illusions. Most famously, the Laurel/Yanny internet phenomenon of 2018 brought speech interpretation illusions into the spotlight. It also demonstrated the incredible subjectivity of our hearing. Similarly, The McGurk Effect presents a puzzling phenomenon in the interaction of vision and speech. When a visual component of a person mouthing a sound is paired with a different sound, listeners perceive neither of the two sounds, but instead a third sound.

Dr. Deutsch has amassed an immense number of Stereophonic Illusions including Phantom Words, Binaural Beats, the Glissando Illusion, the Octave Illusion, the Scale Illusion, the Tritone Paradox, and more. Her work shows us how differently people perceive the same sounds. When we listen to speech the words we perceive are influenced by our expectations, knowledge, dialect, and culture, in addition to the physical sounds we hear. Much of her work has also demonstrated how left and right-handedness influences how complex sounds are synthesized and localized in our heads. In the Tritone Paradox, utilizing sequentially played Shepard tones a tritone apart, some listeners hear the tone ascending while others hear it descending. The potential for designing sounds in which some of the audience experiences the inverse of what others experience is, to me at least, a riveting notion.

While this is brief overview is the tip of the ever-expanding metaphorical iceberg of auditory illusions, I have found that looking into psychoacoustics and auditory neurology provides incredible design techniques and ideas that are not always at our disposal. The potential here that I’m so excited about, is to create audience experiences that rouse questions about the subjectivity of their perceptions of the world around them. Audiences can leave the theater not believing their ears. It also illuminates a greater need for interdisciplinary collaboration and cooperation between fields that often feel disparate: psychology, neurology, audiology, engineering, music, sound design, etc. In my own work, I have yet to utilize almost any of this material (with the exception of spatialization techniques, of course), but it is leading me to think about designing for the whole head, the ear, the brain, and the mind. I so look forward to the continued integration of auditory illusions in theatrical designs, creating sound magic.