The Changing of the Guard – Training subs and replacements on a show

Last month, in Tips and Tricks for Subs and Replacements, we discussed how to put your best foot forward when learning to be a sub or replacement on a show. This month let’s look at the other side of the equation, when you are the one running the show and someone new is coming in either to sub for you, or to take over the show entirely. We will mostly discuss training subs in this post, but the training principles and tips should apply in both scenarios.

Why is having a well-trained sub so important? Well, the old saying “the show must go on” applies equally on stage and backstage! Just as actors have understudies for their roles, it is important that no one person’s health or availability is the “single point of failure” on a production, such that the show literally cannot go on without them if they must call out. Additionally, you don’t want the show to simply “go on” without you. You want it to be as good as it is when you’re the one mixing! When your sub is mixing the show, they are representing you, your work, and the entire sound department, so you want to know you have someone who is going to do their best job and be a good ambassador on your behalf.

I like to break the training process into 3 phases: Pre-Prep (before your sub’s first official day), Training (when your sub is learning to mix the show), and Hand-Off (when the sub finally gets “hands-on faders” and starts mixing the show). Depending on your sub’s prior mixing experience, this process can take anywhere from a few days to a month. Typically, I will ask for 16 performances (2 weeks, assuming 8 shows a week) to complete this process, and I have this is the typical timeline in NYC.

Phase 1: Pre-prep

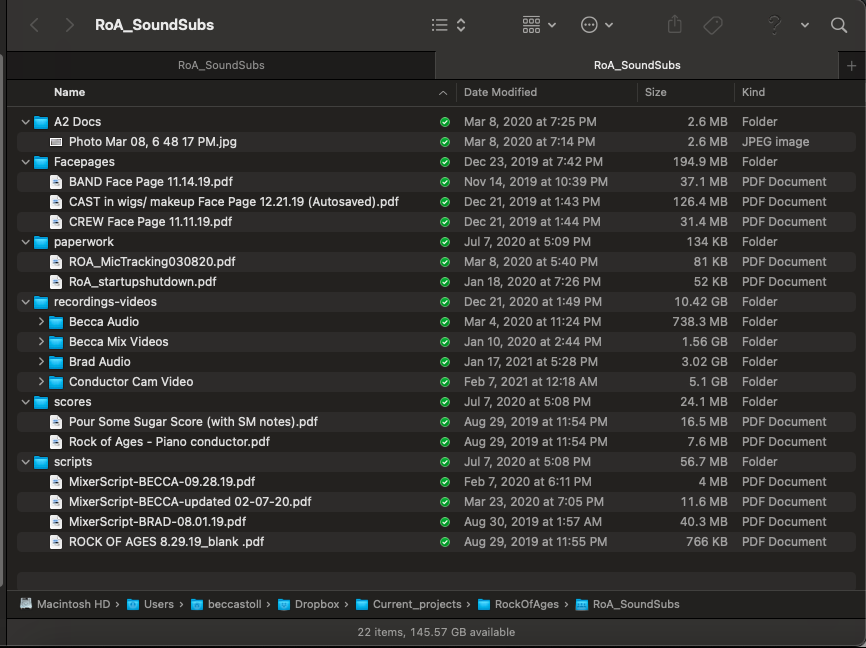

There is a lot you can do to make things easier for your incoming sub before they are even hired. The first of these is to maintain a good mix script! If you read my last blog, you know that I take paperwork and formatting very seriously, because they’re the best tools we have to convey all the information that is needed to mix the show correctly. If your script is paper, think about making a digital version, or at least a scanned PDF. That way your sub can have access to all your notes as they put together their own copy of the mix script. Collect any additional paperwork or training materials that might be helpful to them and organize it all in some sort of shared folder. For example, if a new sub was to join my show, they would be added to a private Dropbox which has my mix script, a blank script, the score, face pages (for learning people’s names), startup/shutdown instructions, show recordings (audio-only and conductor cam), and hands videos that my current sub filmed when he was training so that he could reference them while practicing. Back when I was a stage manager, one of my sayings was “the book matters more than you do,” and this idea certainly applies here. When your sub is mixing for real, you won’t be there to answer questions, so as much of that info as possible needs to be written down and easy to reference.

Phase 2: Training

Once your sub is in the building and training has officially begun, you will want to give them at least a few performances to get familiar with the show, the mix, the pace, and the sound before they start practicing. They should watch the show from the audience at least once before moving to FOH to shadow you. Once they are shadowing you, this is when they can be building their script, taking notes, and asking questions. On Rock of Ages, I had a small table with a video shot of the stage over to one side, plus our console had an overview screen that I could angle towards my sub at the table. This allowed them to watch both the show and a mini-version of my DCAs moving in order to see my strategy for making certain pickups in real-time, and without having to be right on top of me at the console :). If you’re able, try to explain certain things to your sub in real-time while you’re mixing. The more context you can give your sub for why you approach scenes the way you do, the easier it will be for them to mimic your moves. Everyone learns their own way, so give your sub room to do the prep they need, whether that’s watching you, marking up their script, or mixing along with pennies or a practice console. If they are newer at mixing and need more guidance, do your best to instruct them on what to focus on as they train, and what notes they should put in their script to make things as clear as possible.

Phase 3: Hand-off

It’s finally time for your sub to start doing some real mixing! Rather than just have your sub dive in head-first and mix the whole show their first time, it’s best to give them bits and pieces of the show to start with and build up from there. There are 3 common methods that I know of for handing off a show: “top-to-bottom,” “bottom-to-top,” and my personal favorite, “inside out.” If you are handing off a show “top-to-bottom,” you will have your sub start by mixing the beginning the show, and then you will take over and do the rest at a logical “hand-off” point, such as during an applause break. The next night, they will again start mixing from the top, but go on for longer before handing back to you. This way, they are always mixing the show in sequential order, and they will always be starting by mixing a part of the show that they have done before. This can help to build confidence, depending on your sub’s experience and personality. “Bottom-to-top” is the same method, just backwards. Your sub starts at the end of the show (for example, with the finale) and then your “hand-off” point moves earlier and earlier. Handing off “bottom-to-top” can be great because the regular mixer sets the tone for the show, and the sub has a benchmark that they can follow once they take over.

Finally, handing off “inside-out” is when you have your sub start with mixing small sections in the middle of the show, then build out from there until they reach the “bookends” of each act. I love this method because I can tailor my sub’s hand-off schedule to them more specifically. It also has the same advantage as “bottom-to-top” where I can start things off and give the sub a sense of where their levels should be that night. Typically, I will first give my sub some easy stuff to mix in the middle of each act, such as intimate dialogue scenes and solo or two-character songs. I’ll try to make sure that they get a section with some sound effects if the show has those so that they can get used to juggling that responsibility with making their pickups. The next day, I will either add entirely new chunks of the show to their list or extend the length of the chunks they are already doing. Again, this is dependent on the content of your show and the experience of your sub. In this method, the original A1 will find in a few days that all they are mixing is the beginnings and ends of each act, and finally, the whole show will be “handed off!”

These methods all take some advance planning to make sure that your hand-offs are clean, and it’s good to make sure your sub, stage manager, and music director are all privy to the plan each night. You don’t need to go into major detail about who is mixing which exact lines of dialogue, but those folks will be able to give good notes about what they are hearing and what might need adjusting between you and your sub.

Optional Phase 4: Noting and Brush-Ups

If time allows, try to make sure that your sub-mixes at least one entire performance by themselves prior to your planned absence day, if applicable. If things are progressing well and your show is fully handed off, the last thing I like to do is give my sub one show where I am not at the console with them, so that they can practice “flying solo.” At this show, I will sit in the back of the house so that I can get to the console quickly if I need to, but mostly I will try to write my notes down and stay out of their way! This really is the only way that your sub will learn to solve problems and make decisions without you there to help, which is exactly the goal of training them in the first place!

Once your sub is fully trained, you should make a schedule for them to come in and mix a brush-up performance every few weeks, with you noting them from the house. Even if you aren’t planning to take a day off, it’s important to make sure your sub stays fresh, and that can be hard to do if they go months without mixing a performance!

What if your theater isn’t in the habit of hiring and training subs? I know from personal experience that it can be hard to sell a producer on this idea, especially in low-budget venues or on short show runs. If you are met with resistance, ask your producer to think of it this way. Training a sub is like taking out an insurance policy for the show. Putting in the time and resources to train a sub in advance will likely result in a higher quality mix than if someone untrained must attempt to mix the show “cold.” Or in the worst-case scenario, the producer might have to cancel an entire performance and refund everyone’s tickets. Hopefully avoiding both these outcomes is in their best interests too!

On a side note, one of my sincerest hopes is that when theater returns post-pandemic, the need for trained subs, paid sick days, paid personal days, and thorough contingency plans will be taken much more seriously by everyone. No one should ever feel like they must “power through” if they aren’t feeling well, and I think that we all now realize that having a sick person in the building is not worth the risk it poses to everyone else! No more “war stories” about sick A1s trying to mix with their sinuses totally blocked or with a nausea bucket next to them (I, unfortunately, speak from personal experience on both). Also, we have always known that this work can be mentally taxing, and I hope that when we reopen workers will feel that they can advocate for themselves better in that arena too, whether by asking for support outside of work or taking a mental health day without fear of repercussions.

I hope this post and my previous blogs have helped to shed some light on this important aspect of running shows! Whether you are the sub or are training the sub, these tips and tricks will help you make sure that your show sounds the best it can, regardless of who is mixing it.