Maxime Brunet is a freelance live sound engineer, primarily mixing FOH & tour management. She also works in music venues as both a FOH & monitor engineer. She has been working in live sound for ten years and touring for six. She has toured with a variety of artists over the years, including Wolf Parade, Chloe Lilac, Operators, TR/ST, Kilo Kish, Marika Hackman, & Dilly Dally.

Early Career – DIY Punk, Radio, & Trial By Fire

Growing up in Ottawa, Canada, Maxime played in DIY punk bands, promoted shows, & attended as many concerts as she could. She started her professional audio journey when interning at a community radio station in high school. After completing her internship, she was offered a position as the production coordinator: she recorded ads and station IDs, as well as helped volunteers edit interviews, and trained them on how to use the recording equipment and DAW. She developed an interest in mixing and began recording and mixing her own bands, in which she played bass & sang.

Maxime attended the University of Ottawa, where she studied political science. During her undergrad, she started shadowing live sound engineers around town. Eventually, she was hired at Café Dekcuf/Mavericks, a popular two-story venue. It was ‘trial by fire;’ she recounts learning something new every shift and really having to work on understanding how to fight feedback, properly run a soundcheck, and learning how to mix. Though she had already toured as a musician, she really wanted to try her hand at being a touring tech. She asked bands who said they liked working with her to take her on tour. In 2014, her hard work led her to tour North America & Europe with the noise metal band KENmode.

In late 2014 she moved to Toronto, where she got a job at The Mod Club, a 650 capacity local venue. This position was instrumental in helping her to hone her abilities. For the first time, she was working in a venue where there were 2 engineers on her shift – FOH & monitors. She found & worked with a community of inspiring audio techs in Toronto, who pushed each other to increase their skills, shared job postings, & looked out for each other. This was the first time she really felt like she was part of an audio community.

Perseverance & Breaking the ‘Grumpy Sound Guy’ Stereotype

❖ How did your early internships or jobs help build a foundation for where you are now?

I learned perseverance through mixing my first shows – my mixes certainly didn’t sound great at first, but I realized that if I didn’t keep working at increasing my skills I’d never get anywhere in this field. Audio is a long-term job, we’re all continuously learning new skills and improving.

❖ What did you learn while interning or on your early gigs?

Sometimes it’s not about being the most skilled, it’s about how you work and relate to the people you’re working with. I certainly wasn’t the most technically skilled mixer when I started working in venues, but I genuinely cared about the sound the artist wanted to achieve and tried to develop relationships with the musicians instead of just demanding they turn down their amp. I realized from working alongside one too many “grumpy sound guys” that I would get further if I was nice to the artists, promoters, & crowd.

❖ Did you have a mentor or someone that helped you?

I’ve had many mentors, and they’ve all been instrumental in helping me achieve success in this field. From Slo’ Tom at Zaphods teaching me the ropes, to Ben at Mavericks answering all my questions and helping me improve my mixing skills, to Keeks in Toronto pushing me into the professional touring world, I’ve had a lot of support and I am very grateful.

Current Career & Adapting to a Post-Covid World

❖ What is a typical day like for you on the job?

As a touring tech, waking up in a hotel, answering emails before we start our daily drive, loading into the venue, making sure hospitality has arrived, soundchecking, making sure the band is comfortable, making sure the show runs on time, mixing the show, settling the show, loading out, & getting everyone settled for the night in the hotel.

❖ How do you stay organized and focused?

I use apps like Mastertour to upload day sheets and Google Drive to keep documents remotely – it’s always important to have important documents (insurance, passports, etc) on a cloud. I upload as much information as I can before the tour starts; as a tour manager, it’s important to be organized and know what each day looks like ahead of time in order to plan drive times, etc.

❖ What do you like best about touring?

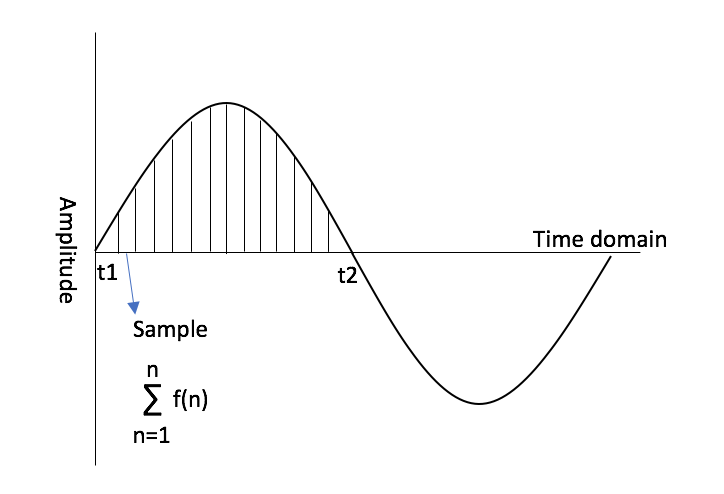

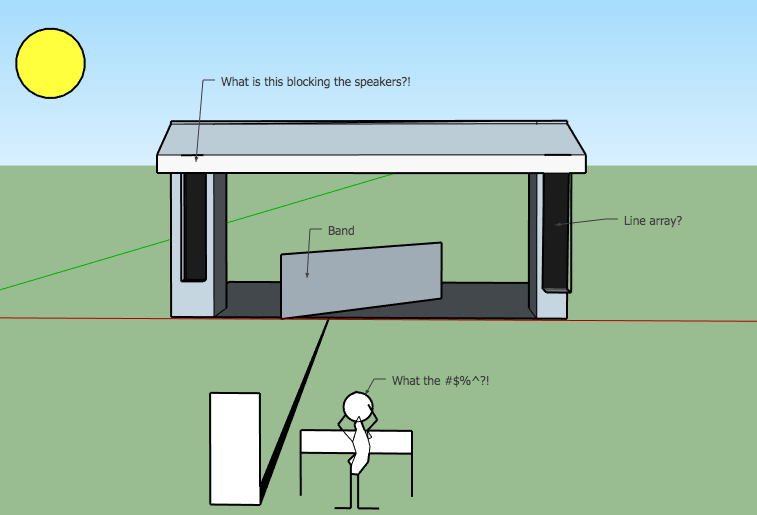

Mixing in a different city every night. I am a person who loves daily challenges, I don’t love routine (though there is a certain routine to load in and shows).

❖ What do you like least?

The long hours & being away from friends and family. I’ve made a lot of great friends touring, but it can be difficult to miss events that family and friends can attend (for example I am always working Friday nights, which is often when people who work 9-5 host parties).

❖ What is your favorite day off activity?

Exploring new cities, eating local food (particularly sweets!), having a good coffee, and catching up on some reading. I also love sending postcards.

❖ What are your long-term goals?

I’d like to get back into studio mixing. I recently purchased an audio interface again and a pair of studio monitors, I’d love to mix friend’s musical projects. When touring comes back, I’d also love to get back on the road – I miss it so much!

❖ What are your short-term goals?

Making it through 2020. This year has been quite a challenge, but I’m grateful to have a strong community of tech friends who checked in and supported each other through these tough times.

❖ What, if any, obstacles or barriers have you faced?

I, fortunately, haven’t faced too much sexism in the field, but I’ve definitely had to explain to club owners that I was qualified to mix or had bands tell the local crew to not make rude comments about me.

❖ How have you dealt with them?

I remind myself that sexism is, unfortunately, a part of modern society and try and brush it off as best as I can. I have a job to do, someone’s rude comment about me being a woman won’t stop me from having a great mix that night. As I was told by a musician: “we hire you because we know you’re great at your job”. I still think about this comment, and it reminds me there’s a reason I’m mixing on these tours – I am talented.

❖ How has your career been affected by Covid-19, & how have you adapted to the current situation?

As a live engineer, my work disappeared in March for the foreseeable future. As things are very uncertain for the music industry at the moment, I decided to return to school to increase my skills. I am currently a student at Concordia University in the Graduate Certificate in Communication Studies. I am planning on applying to Masters programs in 2021.

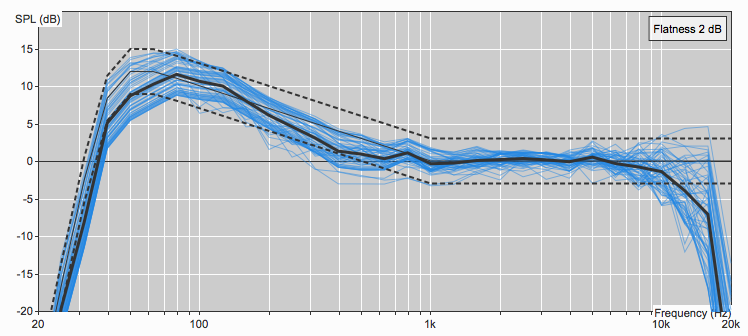

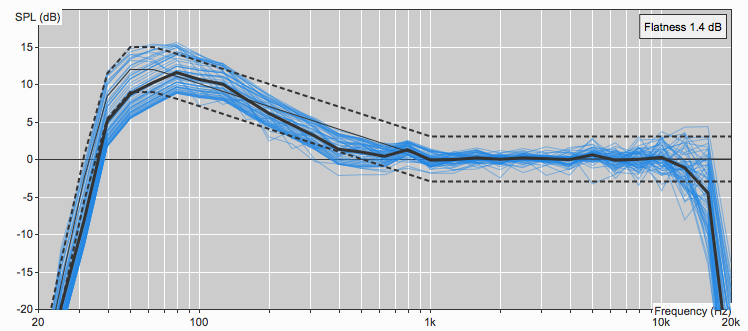

❖ Favorite gear?

Digico consoles, Telefunken & Sennheiser microphones. I’m fortunate enough to tour with talented artists: a good band will sound good on ”bad” PAs and lower-end mixing consoles, but it’s nice to have good tools on hand. I always travel with my own vocal mics (my personal favorite is the Telefunken M80); it’s a definite advantage to use a mic with a tighter pickup pattern on loud stages to really make your vocals pop in the mix.

❖ Must have skills in the industry?

Problem-solving and the ability to multitask.

❖ Advice you have for other womxn who wish to enter the field?

Be determined, persevere through those first few rough gigs and keep looking for opportunities. No one is instantly great at their job, we have all had bad gigs. Live audio isn’t the kind of field where jobs will just appear on a website, you need to constantly network and look for the next gig. It will be harder to be taken seriously as a woman and you will face barriers, but I do think that artists and management are starting to understand the value of hiring women.

More on Maxx: