Gain Without the Pain: Gain Structure for Live Sound Part 2

In my last blog, I outlined the basics of gain structure, and how to get to a good starting point for your mix. This time I want to discuss a few situations where you might take different approaches to how you set your gain, and why.

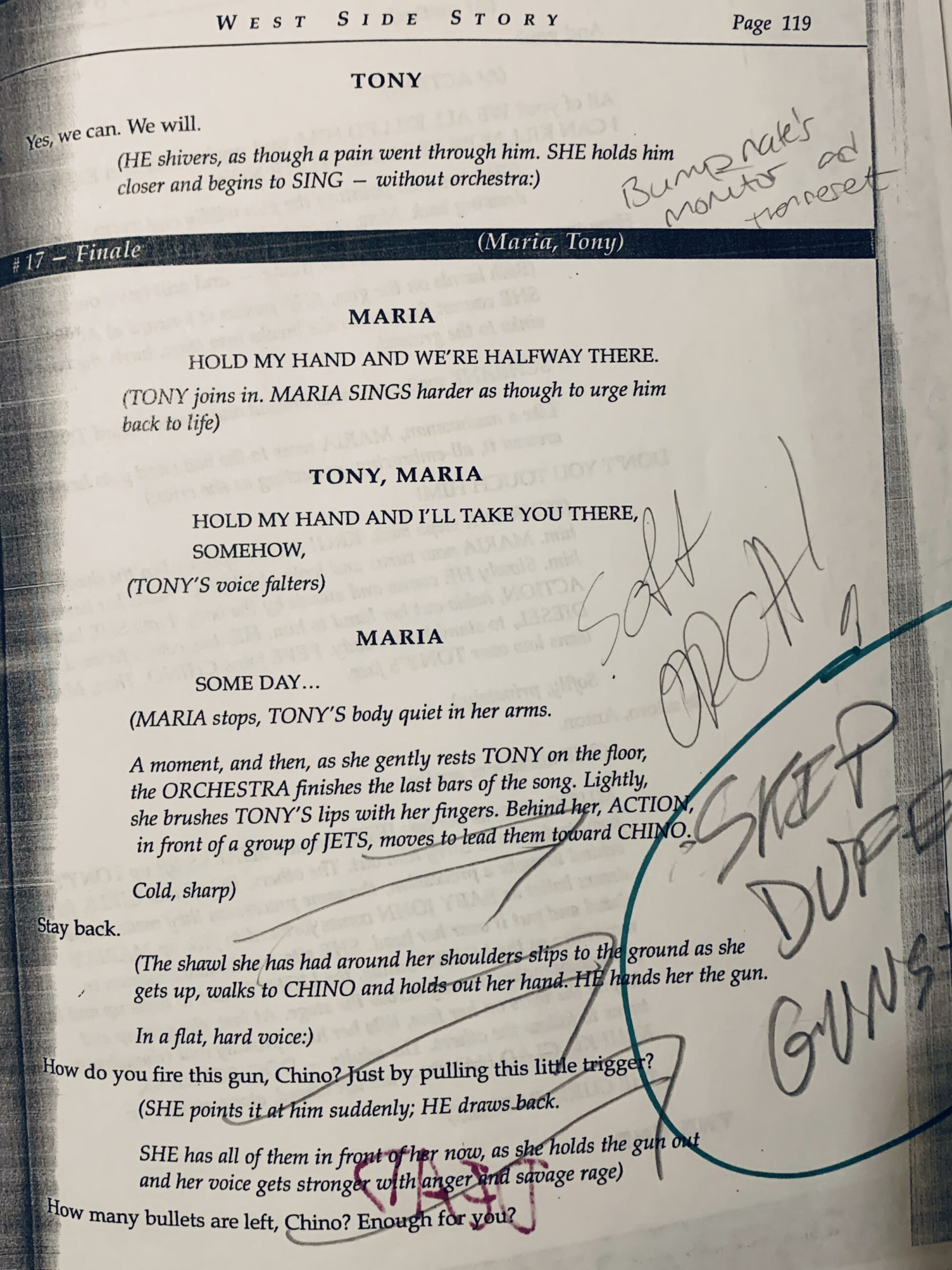

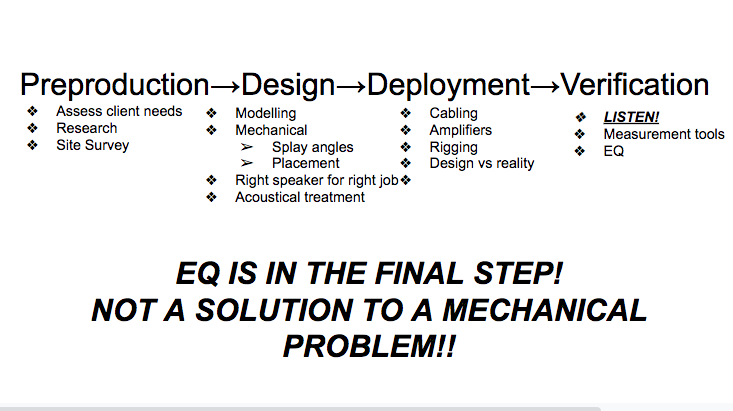

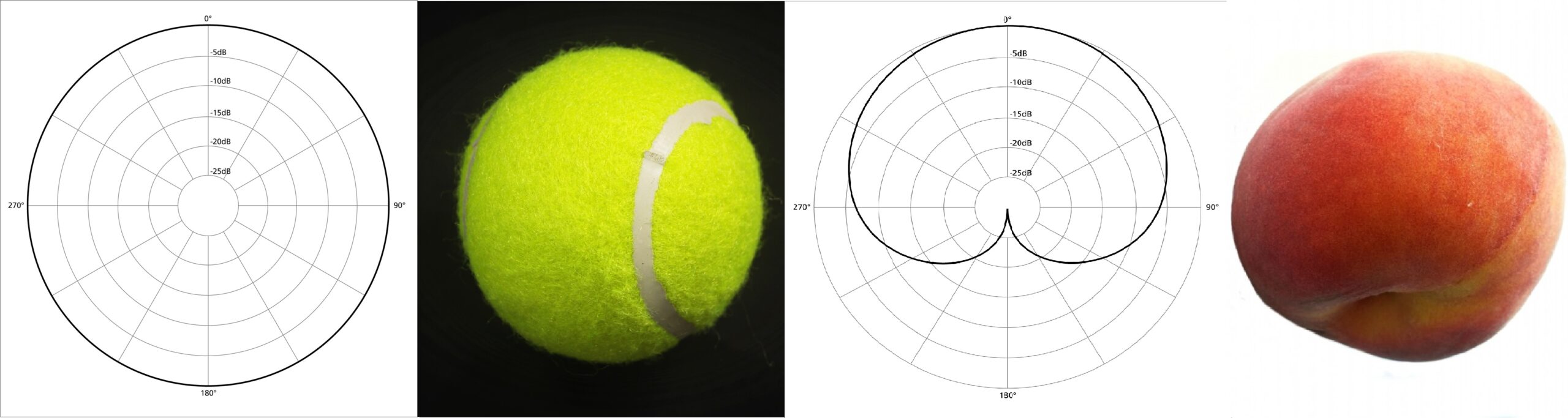

I like to think of gain as a tennis ball growing out of the mic if it’s omnidirectional, or a peach for cardioid mics, with the stalk-socket (is there a word for that?) at the point of most rejection. Bidirectional/figure eight mics always remind me of Princess Leia’s famous hair buns in Star Wars. Whatever you imagine it as don’t forget that the pick-up pattern is three-dimensional. There can be a bit of a subconscious tendency to think of pick-up patterns as the flat discs you see in polar plots, so don’t fall into that trap! The main thing to remember is that as you increase the gain, you’re expanding the area in which the mic will pick noise up in every dimension, not just in the direction of what you want to amplify. This will be more of an issue in some circumstances than others, so they can benefit from different approaches.

Quiet singer, noisey stage

My first example is the one I encounter most often and causes me the most issues. You have a loud band on a reverberant, noisey stage, and you’re trying to get the vocals audible, or even nice! This can be a bit of a challenge even with a strong singer, but a quiet vocalist can seem impossibly lost in the mix. Thinking back to my previous post, the problem in this situation is that the other instruments, the crowd and everything reflecting back off the walls is keeping the noise high in the signal-to-noise ratio. Turning the gain up will just bring more of that noise into your board and muddy the mix. Upping the gain for monitors will increase the likelihood of frequencies in the monitor mix being picked up by the mic, which feeds back to the monitor, which feeds back to the mic… which creates feedback!

In an ideal world, the other players would set their instruments at reasonable levels, and the vocalist would sing loudly, close to the mic. This would increase the signal-to-noise ratio naturally. Unfortunately, this often doesn’t happen for one reason or another, and you need to fix it at the board. In these situations I try to keep the gain as low as possible while still picking the vocalist up. I use high and low pass filters to get rid of the unnecessary noise in ranges away from the vocalist’s frequencies. I might EQ a few bits out of the vocal channel where other instruments are being picked up more than the singer, and might EQ out some vocal frequencies from other channels to give them some more space to be heard. I then try to have the fader as high as possible while still leaving some headroom. Setting your master fader or monitor mixes at +5 instead of 0 can give you the extra volume you need, while keeping the gain as tight as possible. I very rarely find myself needing to turn an entire mix-up mid-show, and if it comes to it I can just turn up all the sends from the channels instead. There are plenty of other tricks to get vocals to stand out in your mix, but that is beyond the scope of this post.

Wandering keynote speaker

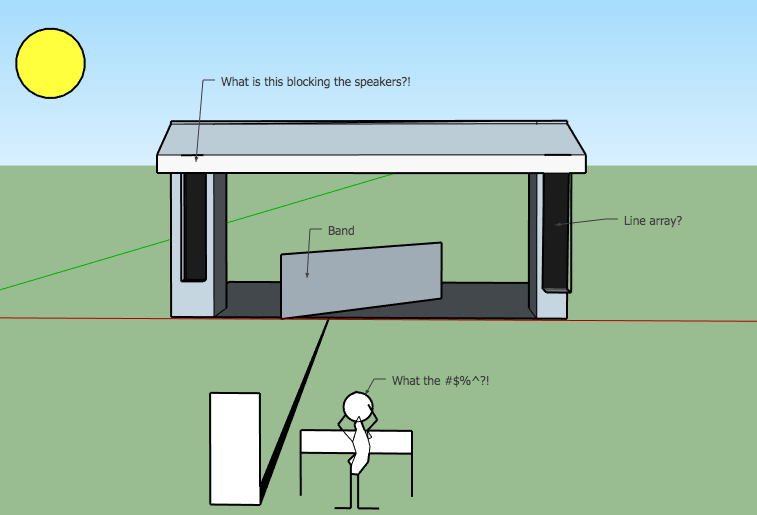

On the other end of the noisey gig spectrum is the classic corporate speaker who won’t stay near the lectern mic. I think one of the most misunderstood aspects of live sound by people outside our industry is that the mics pick everything in their field up, in every direction, whether the sound is intentional or not. For example, I had someone loudly shuffle their notes and bang them on the lectern, cough and say something privately to an assistant right by the mics as they were supposed to start their speech. They then fully wandered the 20 metre (roughly 60 feet) wide stage, talking at normal conversational volume, expecting the mics to pick them up perfectly, no matter where they were. Quickly muting the channel when it’s apparent the speaker is still preparing solves the first issues, but there’s not much you can do about audibility when they’re metres away from the mics. This is an extreme example. However, it is very common for people to stand at a lectern but talk quite far away from the mics, turning their heads repeatedly to gesture towards their presentation.

Hopefully, the stage at a conference isn’t as noisy as a rock band in a club, and the audience are mostly quietly paying attention rather than screaming and cheering. It’s less common to have stage monitors, and with any luck, the PA is quite far away from the mics. In this case, you can get away with turning the gain up, to catch more of what they’re saying. Just remember to add a pretty strong compressor for when they inevitably lean in and suddenly talk loudly, directly into the mics. This can also help if you have several people using the lectern without soundchecking. You can set the mics to as high a gain as is stable, so even if they’re quiet you’re covered. If they’re loud you can always turn them down.

Popping lavalier or headset mics

You don’t always want your sound source as close to the mic as possible. Plosives in speech; the consonant sounds made with a burst of air, like p’s and b’s, can sound horrible on sensitive mics like lavaliers or headsets. These mics can also pick up too much sibilance. In these cases, it’s best to move them slightly further away or off-axis (by a matter of millimeters) so they aren’t in the firing line of the speaker’s breath, then turn the gain up to compensate. You might have noticed that lavaliers are often attached completely upside down for recording or TV. This stops the mic capsule being battered by those plosives and reduces sibilance, and the recording engineer can turn the gain up as much as needed without worrying about feedback because there are no speakers in the room.

I hope these examples have helped you to see how gain structure is just another tool in your mixing bag of tricks. There are good rules of thumb to follow for getting a decent signal-to-noise ratio quickly, but they aren’t written in stone. If you need to move the balance around or adjust different aspects of the channel strip to make your particular situation work, just try it (gradually if the show is already live!). It’s easy to talk about what the correct approach is in a textbook situation, but real life is very rarely ideal. Do what you need to do to get it working. If it sounds good in the end, that’s all that matters.