Preconceptions in Human Hearing

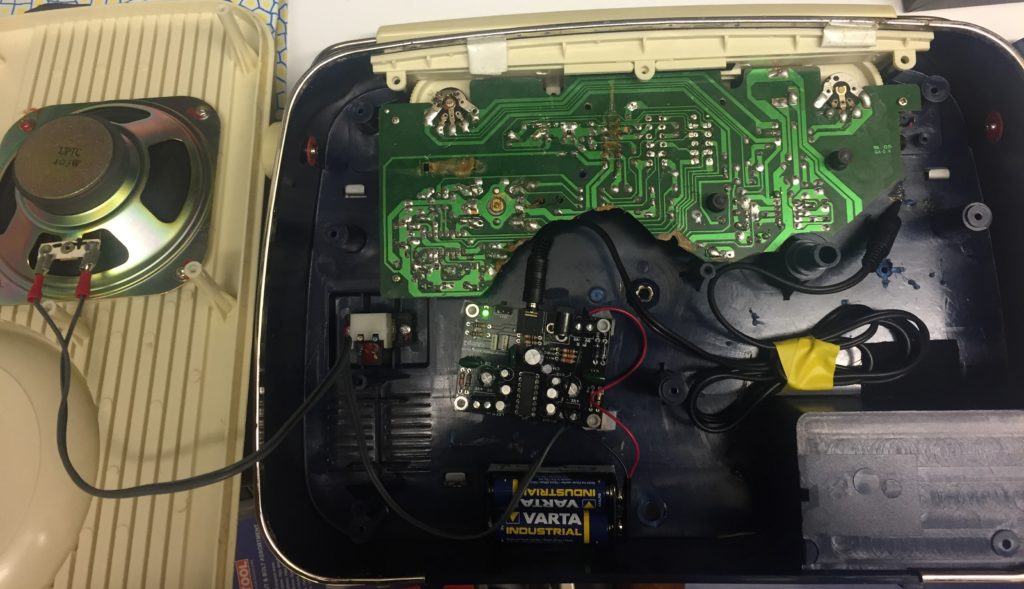

As sound designers, we often have to fight against what something actually sounds like, and what audiences expect things to sound like. For example, an authentic phone ring might not necessarily fit the tone of the piece, and actually, a phone from a different era would suffice in creating urgency and tonality.

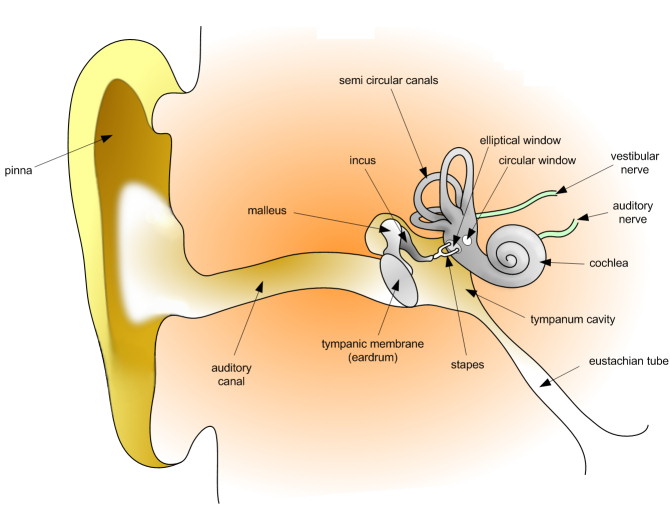

As a starter for ten, human hearing is fairly straightforward. Sound waves are transmitted through the cochlea which then eventually reach the Primary Auditory Cortex and the syntax processing areas of the brain. We can say that these processing areas of the brain share the sound waves and do their best to find some rhythm and harmony in what we are hearing. This is because of the linguistic processing tendencies we have, and our innate need for understanding and communication.

Our perception of sounds stems from our memories, and the human memory is typically untrustworthy. How many times have you shared a story and had someone remember a completely different version? We could argue that it’s the same premise for sound.

While it’s true that our echoic (hearing/auditory related) memory lasts longer and has a quicker processing time than our iconic memory (visual related), and could therefore be described as more reliable; our echoic memory can only hear things once, and things once heard cannot be unheard.

This is also where our short and long-term memories come into play. If you were sitting in a packed auditorium at front of house and heard an announcement (the quarter call, for instance), nine times out of ten we would hear the call, process it, and then completely forget about it. Should somebody then ask you, five minutes later, what that call was, you may just be at a loss as to what it was, but could probably remember the tone, the clarity, and more about the speaker’s voice than the actual message. There are a number of factors to blame here.

Upon recognising that there was no immediate danger, you would blend out the rest of the call, and continue your own conversation. This is our basic selective hearing, but what of the rest of the call? We attenuate the rest of the information and store it in case it becomes useful, but it’s not always remembered accurately. This is further because our memories store a lot of information, whether it be in the long-term or short-term, and intrinsically we link memories to other memories to aid said storage. Of course when talking about sound, and sound effects, it entirely depends on the context of how/when/where a listener has heard them before – no two natural sound effects will ever be the same, and nor will their memory recalls within individual human beings.

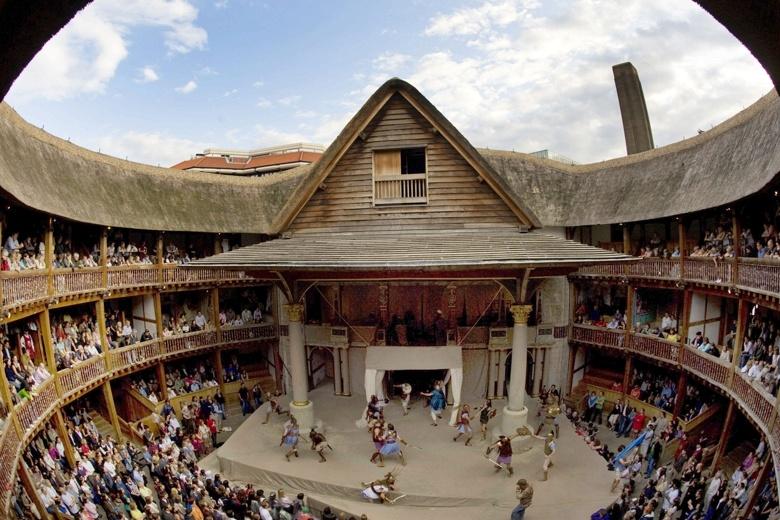

But what does all of this mean for sound design? And particularly sound design for theatre? If we are playing on audience perceptions of what sounds, atmospheres, or even conversations between actors should sound like, then it depends on the effect being sought. If we’re talking a straight play, then a doorbell from 1911 should probably be true to the text – this means a bell on a pull.

On the other hand, I have absolutely used a recorded shop doorbell because it fitted the tone of the piece better. The bell was, due to pitch, smaller than any of the real house bells we tried, which meant it was a slightly lighter sound, and therefore more whimsical. Of course, this steers us into the territory of scenes in a play, and their overall tones (not to be confused with musical tones). A big old rusty house doorbell would often seem too clanky and boisterous for the entrance of the next-door neighbour (unless, of course, this is the exact effect that you’re heading for).

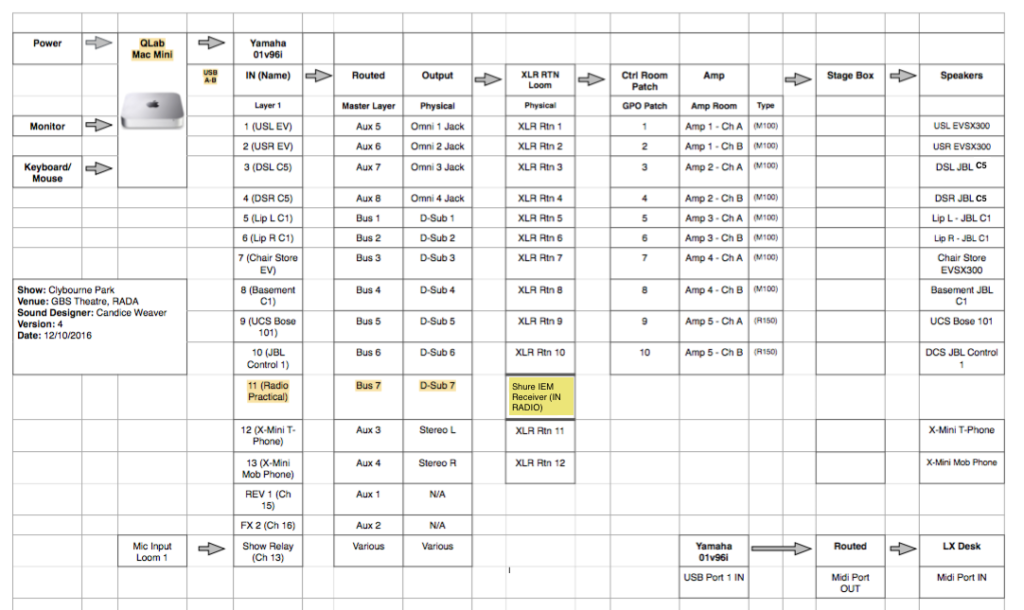

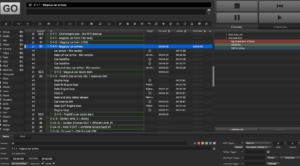

Sound designers will often never use just one sound effect to attain the overall effect that they are seeking; this may be as part of a sequence or even underscore/atmosphere. As we can see below from my recent show A Little Night Music, I used multiple tracks to create two car arrivals:

Sound designers will often never use just one sound effect to attain the overall effect that they are seeking; this may be as part of a sequence or even underscore/atmosphere. As we can see below from my recent show A Little Night Music, I used multiple tracks to create two car arrivals:

It’s often the textures of the sounds that I aim to create when sound designing, and often they do end up being true to what authentic/real-life things sound like, but more often they do not. This can often be for the reasons stated above. It can also end up being that, again, they do not fit the set, tone, or overall direction of the piece.

This is where the overall direction, sound design, and artistic licensing come into play. We can, with our best intentions, want something to sound authentic, however realistically, as designers and artists, we will borrow from different genres and times to make happen what we want to happen. This again, however, can come back to our own personal memories and experiences of sound and effects, and the ideas that they give us in terms of what we want to create.

Ideas fuel other ideas, as do our memories and creative minds, so the more that we feed into said ideas and the ethos of our creations, the more we contribute to the expectations of what things should, or could, sound like.