Audio Guides and Creating Intimate Audio Outdoors

I’ve been approached to work on audio guides in the past, but for one reason or another, never actually got to work on one. So when a director at the Arcola Theatre got in touch with me about sound designing an audio guide for their summer outdoor theatre project, I said yes, please!

The project was a community performance-based outdoor installation in East London, UK. Supported by the local council, the experience focused on personal and social responses to mental health and well-being. One area would have pop-up performances and participatory activities like group yoga and dancing. The other was a sixty-minute audio guide that would take audience members through a constructed “labyrinth” that explored the process of “getting better.”

In theory, sound design for audio guides is quite straightforward when compared to standard theatre sound. As you’re designing for headphones or earphones, you don’t have to worry about speaker placement, so everything can be done in the studio and delivered ready to go. Of course, you can always have added layers of complexity such as multiple delivery systems and infrared or RF triggers, but ours was a much simpler setup.

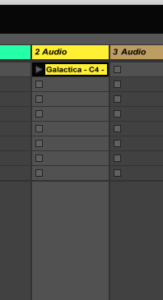

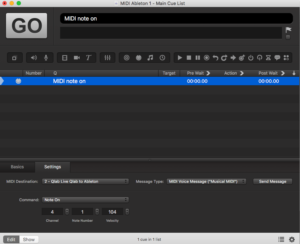

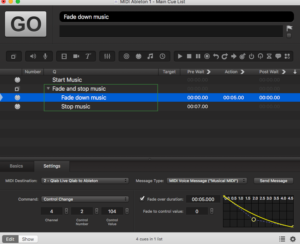

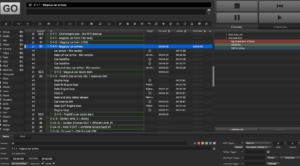

We had hired a single wireless Sennheiser 2020-D tour guide system, which would play a single continuous file from five iPods connected to five different transmitters on separate channels for our five audience groups. Each group would be guided by silent performers through a series of different spaces, including a family birthday dinner, doctor’s surgery, surreal interactive WebMD bingo game, and calm centre.

With any audio guide, the most important element is the voiceover, as the audience relies on this for context, explanation, instructions, and in the case of this project, the narrative thread. Recording clear, high-quality voiceovers was, therefore, my main priority.

In an ideal world, I would always record all voiceovers for a show in a professional studio with a voice booth – usually my own. In the real world, budgets and actor availability often don’t allow for this, which is why I had to record the majority of the voiceovers for this project in a rehearsal space in the theatre. I have a portable voice recording booth for situations such as this, but without time to treat the room further, there wasn’t much I could do about the reflections, nor about the level of external noise. At one point, we were competing with a swing dance lesson in the next room – not the best accompaniment to an emotional narrative about mental health!

I know that it’s often possible (though never preferable) to get away with less high-quality recordings in a theatre because when played out through speakers, the acoustics of the venue will mask a lot of the recording faults. Headphones are a lot less forgiving, however, and I was concerned that the less-than-professional recording set up, not to mention the increased noise floor, would lower the overall quality of the guide.

At this point, I turned to what I knew about the technology that we’d be using – or at least, what I could find out about the technology, as I wouldn’t be able to hear the sound through it until the dress rehearsal.

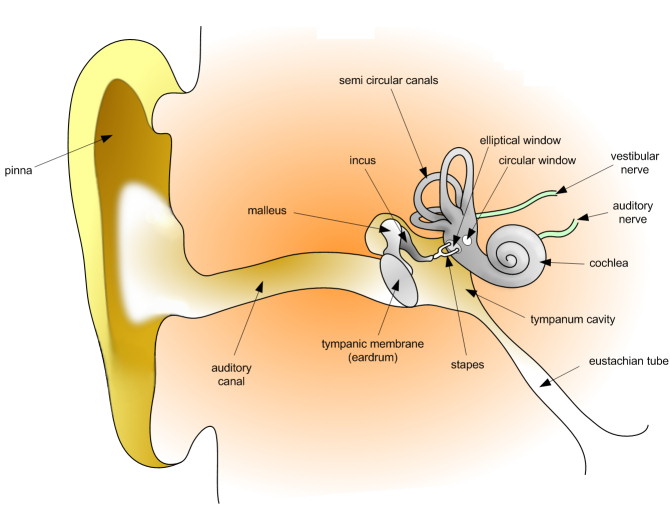

The HDE 2020-D receivers are known as “stethoset” receivers, presumably because they have a stethoscope design where the earphones are attached directly to the receiver by fixed curved handles. The design has practical merit – without headphones, there was no danger of the audience tangling wires or disconnecting the headphones from the receiver pack – but from a sound perspective, it isn’t the best method to deliver a subtle soundtrack. The earphones don’t block out much external sound as headphones would, and the weight of the receiver pack limited how snugly you could secure the earphones into ears. They also had a frequency response of 100Hz – 7kHz. This range is pretty limited, but it worked in my favour for this particular project. Given that the frequency range used for speech transmission (telephones in particular) is around 300Hz – 3.4kHz, I could filter off most of the noise from my recordings and still have an intelligible recording. Filtering, plus the use of background music, masked most of the room sound in the voice-over recordings.

After the recording sessions, my main task was creating two sixty-minute versions of the guide – one with a female narrator, one with a male. After clean-up and editing the voiceovers were all fine, but I was conflicted about how loud to make the background soundscapes. Without being able to hear my audio through the receivers in advance, in the performance environment, it was hard to judge how present they needed to be. I did know that the audio guide would be competing with a live sound system in another area of the installation – but without knowing how loud or how far away this would be, it was tricky to know how much this would affect the audibility of my guide.

The dress rehearsal was our only chance to test the audio through the delivery system, in a performance scenario, while music was playing in other areas of the installation. I quickly discovered that for the audio guide narration to be clearly audible through the receivers, the gain had to be set to maximum at each level – iPods, transmitters, and the receivers themselves. Not ideal, but at least the audience could hear their guides!

The dress rehearsal was our only chance to test the audio through the delivery system, in a performance scenario, while music was playing in other areas of the installation. I quickly discovered that for the audio guide narration to be clearly audible through the receivers, the gain had to be set to maximum at each level – iPods, transmitters, and the receivers themselves. Not ideal, but at least the audience could hear their guides!

Unfortunately, the ambient noise of the performance environment (a public square), plus the loose fit of the earphones meant that my more subtle soundscapes were often inaudible. While this didn’t seem to hamper any understanding the audience had of the performance, some of the more immersive moments lost their impact. Although maybe it was unrealistic of me to expect this with an urban outdoor performance!

If I have the chance to design another outdoor audio guide, I know that I’ll push for a more powerful playout system (for more volume!) and to have access to the delivery system earlier. I’ll also agree on a production schedule that allows for testing the finished audio in the performance space ahead of the dress rehearsal. Finally, I’ll have a more realistic idea of how much subtlety you can realistically achieve in a design delivered through a tour guide headphone system, and how much is actually necessary. After all, as long as the audience can follow the story, you’ve achieved your key goal.