Tips and Tricks for Subs and Replacements.

A lot of folks’ first “big break” doesn’t come in the way that you might expect. Mine was a matter of good timing, mostly. I had just finished a run as the A2 on a small new musical, and during the load-out week, my boss pulled me aside and asked to discuss something with me. The show running at the theater’s main stage had become a giant box office hit and was going to extend its run by an additional month. However, the current mixer on that show had a conflict with the final weeks of performances, and my boss, who would usually cover for him, had other things going on. So, did I want to do it instead?

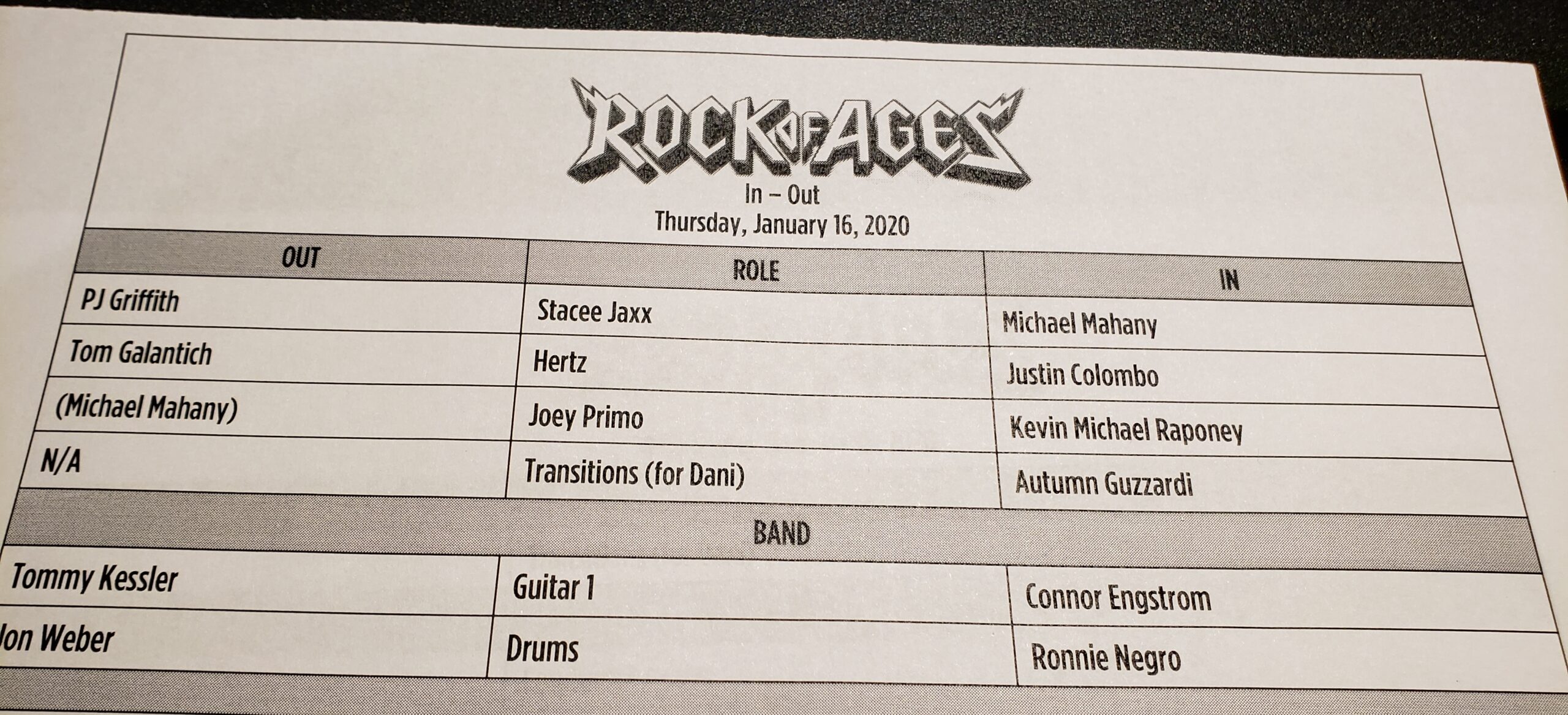

The “In-Out” sheet provided by stage management outlining what understudies and subs are in the show that night. Paperwork created by Pamela Remler, Alison Simone, and Christine Seppala.

I had never been a substitute or replacement on a show before. Ever! I think I might have understudied someone when I was in the ensemble of the eighth-grade musical? But I definitely never went on. Shows in school and college also tend to have really short runs, and often the sprint to get the show open is so crazy that no one gives a thought to having to possibly replace an actor or technician at a moment’s notice. So as a result, these skills are most often learned “on the job.” And they are important skills to have because subbing or replacing someone on a show is how a LOT of people get their start in the industry!

Being a substitute or replacement on a show definitely comes with its own unique set of challenges. Regardless of the situation, it’s always tricky to be the new kid. You’re coming into a group that has already formed, and in all likelihood, they have a bond that comes from having been through the process together up to that point. So, not only are you trying to learn to do your new job, but you are also navigating the social situation and seeing how you are going to fit in. Plus, on the practical side, you will not have been privy to all the decisions that were made throughout rehearsals, tech, and previews, which led to why things are done the way they are. You’re getting a lot of new information but without the underlying context.

Sounds challenging, right? But fear not! There’s a lot you can do to set yourself up for success. So, with that, here are a few best practices for making your transition into a show as smooth as possible.

*quick side note for definitions: I think of a sub as someone who covers for the current mixer in the case of a planned or unplanned absence, and a replacement as someone who is training to take over mixing the show full time. Sometimes they overlap, certainly, there are differences, but hopefully, these tips and tricks will help in either case.

Do as much homework as you can!

One great thing about joining a show that is already up and running is that you don’t have to come in as blind as on an original production. As soon as you’re hired, ask to see the show. See it as many times as you can from the audience before you start watching it from the mix position. This will give you a great sense of how the sound system is laid out, because in all likelihood the show feels pretty different under the balcony vs. second row orchestra. That knowledge will inform your understanding of why the mixer does things a certain way, and how the balance that you hear at FOH is translating to the audience.

If you can’t be in the theater prior to your start date, get any recordings or cast albums that exist and listen to them nonstop. The show that I first came in on as a replacement was a new jukebox musical called Irving Berlin’s Holiday Inn, so there wasn’t a cast album of any kind. My solution? I made a Spotify playlist of all the original songs so that I could at least get a handle on the lyrics, even though the songs in the show were in different arrangements and keys. Ask for any scripts, scores, and show paperwork, so that you’re as familiar with the material as you can be before hitting the ground running.

Read the room

Your first day at the theater should be 99% about listening and observing. What is the vibe like backstage? How does the current mixer interact with people? You can get a lot of knowledge from watching them because they know the people they work with and how to interact with them. They will know which actors want to chat, and which ones would prefer to be left alone to get into character. At least when you’re first phasing in, follow the current mixer’s usual walking paths and tendencies. It will help to create a sense of continuity, because your new coworkers will see that you are not here to rock the boat or upset the existing balance.

Of course, if you get the sense right away that there is some tension, use your judgment about how you might do things differently when it’s just you there. And certainly, you shouldn’t do anything that you are uncomfortable with, or mimic a behavior that you think is making other people uncomfortable. You are your own person, after all. Don’t be afraid to ask your mixer questions about why they do things a certain way or speak to people a certain way once you’re able to talk privately later. But when making those first impressions, take a leaf from the Hamilton book and “talk less, smile more.”

Respect precedent

A follow-up to #2. As we’ve covered, things usually are the way they are for a reason, even if you aren’t sure what that reason is yet. When you start learning to mix the show, do it as identically to the current mixer as you can. Do not change any programming! This is considered rude, as the Mix Bible and Control Group assignments is the original mixer’s main artistic contribution to the piece. Sure, if you’re a replacement, you may do some cleanup of the show file once you’re on your own (spelling errors and such), but for now, mix the original mixer’s show, and mix it their way. Also, if a show runs in multiple cities (e.g., there is a New York production and a touring production), those productions are likely set up to be exact replicas of each other, so that if someone is transferred from one to the other, they aren’t suddenly learning a new way to mix a certain scene. Everyone who mixes the show needs to be able to do it the same way, so you risk creating inconsistencies between mixers if everyone has their own slightly different show file. You should definitely have your own script, set up in a way that makes sense to you, but to make this script you should be copying the notes out of the current mixer’s script exactly, and taking cues where they take them. If you’re replacing someone on a show, your mix will naturally evolve over time, as other folks in the company swap in and out, or after a director or designer comes to note the show. But for now, your job is to do what the current person does.

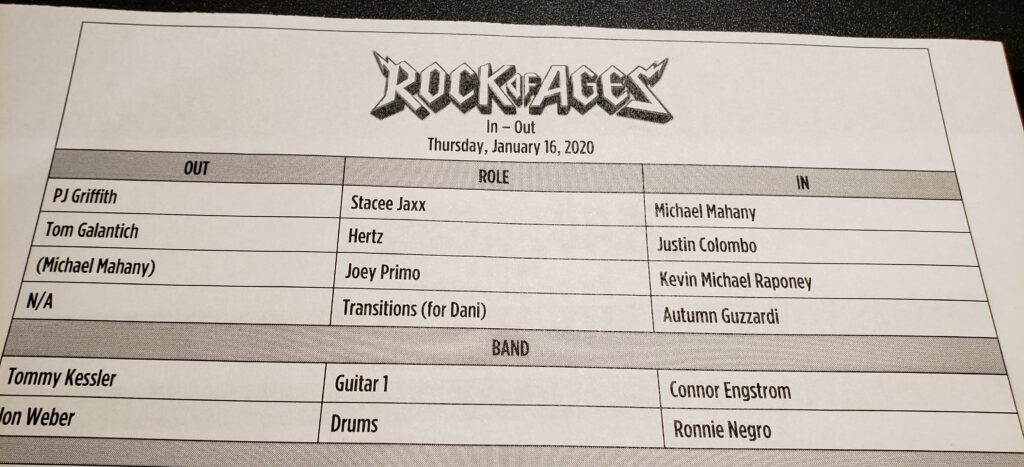

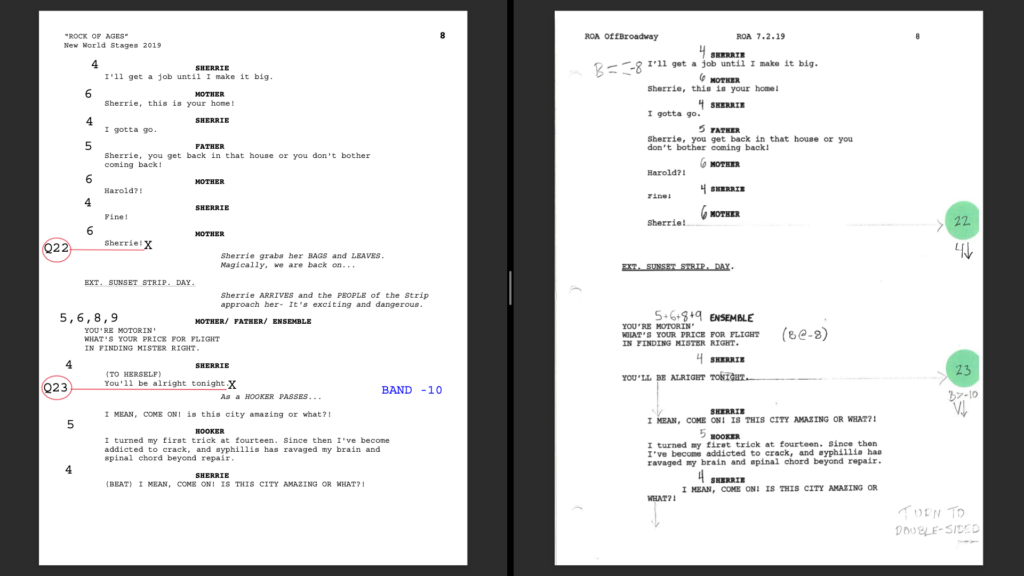

Left-Brad Zuckerman’s original mix script for Rock of Ages Off-Broadway. Right: my version of the mix script. Same notes and info just conveyed in two different ways.

Form smart alliances

In my opinion, the 3 most important relationships that a mixer on a musical has are with the Stage Manager, the Music Director, and the House Manager. Including you, these are the 4 people whose jobs really have no breaks! Y’all are busy the entire show, steering your own related parts of the ship that come together to make a whole production. The stage manager will be able to give you insight into the actors, the general energy backstage, and other things that may help to inform your mix that evening. They can also be an ally when working through scenarios such as a a split track (when there are multiple actor absences and lines/vocals need to be reassigned to do the show “person-down”), a post-show speech, or a special event onstage. The music director is depending on you to make sure the band is coming through well to the house, as well as to the monitors. They will appreciate knowing that you are on their side! The MD knows the show better than almost anyone, and they will know when you might need to make an adjustment based on a sub musician or understudy actor. Finally, the house manager will be able to tell you about any weird audience/patron situations that may affect your mixing. Plus, you can work together to catch audience members using their cellphones to text or bootleg the show, because sometimes you have a better view of the audience than the ushers! This is an ENORMOUS pet peeve of mine personally, and I am grateful to the many house managers who work hard to minimize distractions for those of us who are out in the audience making the show happen.

Learn everyone’s names (and pronouns!)

I used to tell my apprentices that if they only learned one thing in their time working with me, it should be the names of the band members and their subs. I was only half-joking when I said it! This is one of the simplest things you can do to build trust and respect with people. Ask for a face page (a document usually made by stage management, with small photos of the company with their names and pronouns listed underneath them). Study it. If there isn’t a face page, make your own! Get a program or playbill, which should at least have photos of the cast, plus names of the orchestra and crew. Resort to googling and social media stalking if necessary. And if you forget, don’t be afraid to ask! I once walked right into the wardrobe room and said to one of our awesome stitchers “you are always here, and you are so helpful, and I cannot remember your name or pronouns!” Once he told me, I never forgot. Plus, I turned my forgetfulness into an opportunity to build respect not just with this stitcher, but with the whole wardrobe department. It showed everyone in the wardrobe room that who they are and what they do on the show was important to me.

Finally, don’t be afraid to ask questions! The more information you have, the better you’ll do at finding your place and doing your job as well as the person before you. Work hard, be patient, and show a lot of respect. If you’re a replacement, know that you will find your own role in time, so there’s no need to rush it. If you’re a sub, just focus on keeping things consistent on the nights that you are there.

Mid-way through my training on that first sub gig, the music director came up to the original mixer at intermission and said, “the show sounds good tonight!” To which the original mixer replied, “I’m not mixing the show tonight!” That’s how I knew I was doing it right. I had worked hard not just to learn to mix the show, but also to create a smooth and seamless transition between the outgoing mixer and myself. And someone not knowing that that transition had even happened truly was the best compliment of all.

Look out for my next blog in April, where I’ll flip the scenario and talking about TRAINING subs and replacements!