Confronting Bad Behavior

Let’s face it: it can be hard to stand up for yourself.

As women, we are socialized to be friendly, nice, helpful, informative – this works against us. We make up a tiny portion of the audio industry, which makes us more susceptible to disrespect and often means we are on our own (or at least, it feels that way). And in my case, the person I am confronting is practically guaranteed to be physically bigger than me, and probably older too.

I have been asked if I know anything about sound, aggressively quizzed on my resume and technical knowledge, told that I do not belong and have even been flat-out ignored countless times. More often than not, these situations come out of ignorance rather than an intent to harm. After I explain why I am upset they understand, and we are able to move on. But it is still extremely frustrating.

Below are some strategies that I have developed for setting boundaries and confronting these types of behavior head-on. Personally, I like to word my reaction so that the uncomfortableness I am feeling is reflected back onto the other person, but the sharpness of my response varies greatly depending on what was said and whether they are open to listening. Theoretically, you should only have to explain why a situation is not OK once.

Option #1: Play dumb and ask “why”

This strategy works best with offensive jokes and similar lines of questioning. Pretend that everything is a simple misunderstanding on your part and continue asking for more explanation as to their motivations for asking or telling you something. Repeat as many times as necessary.

- Why are you asking me that?

- Sorry, but is there something about me that implies that I don’t know anything about audio?

- What makes you think that was an appropriate thing to say to me?

- Actually, I’m afraid I don’t get why [offensive joke] is funny. Can you explain?

Option #2: Shut it down

Word your response strongly and matter-of-factly. I like to use a polite but stern voice while making it clear that I’m upset. Ideally, the conversation will end there; if the person keeps pushing, I make it clear that I am done talking about the subject by changing the subject back to work (and sometimes explicitly stating so).

- I do not like being called ‘honey. Do not call me that again.

- Let me finish my sentence/conversation.

- Actually, this year is my eighth year in live sound, I wouldn’t be working here if I didn’t know anything.

- I find it a little insulting that you would ask me if I know anything about sound. I didn’t imply that you were incompetent when you got here.

- I have told you already that I am not interested in a date. Can we finish the show like professionals or not?

Option #3: Ignore it

Sometimes the potential consequences outweigh speaking up, or it just doesn’t feel like a battle worth fighting. Dealing with these situations can be exhausting, especially if they’re ongoing or recurring – there’s no shame in simply not feeling like fighting.

In some cases, it’s not even remotely clear what action would be useful. When the man you’re hoping will hire you goes on a 15-minute semi-incoherent rant about how racism doesn’t exist, where do you even begin? It’s been over a year since that happened, and I still have no idea what could have been said that wouldn’t have just extended it. In fact, sometimes ignoring a behavior is arguably the best way to go about things. (I’m thinking of the sound engineers who whistled at me like a dog and blinked their flashlights on and off at me whenever they wanted my attention, respectively).

Option #4: Involve more people

If addressing the matter isn’t working privately, sometimes calling the behavior out with others within earshot is enough to end it. Of course, that depends a lot on the attitudes of the people around you, and whether the perpetrator of the behavior has any shame.

If you aren’t having success, ask someone else to help you. Tell your coworkers what is going on and ask them to back you up or keep an eye out for you. Ask someone with more authority (or perceived authority) to help.

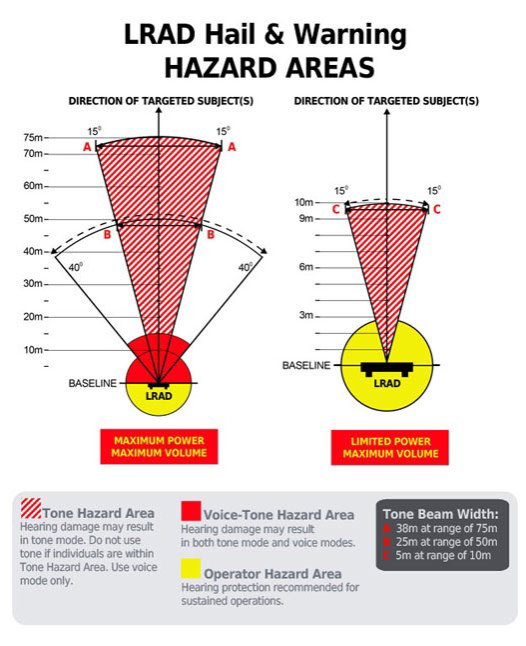

In extreme cases, you might have to find ways to physically deter the person from reaching you. I have kept security next to me to ward off a DJ who repeatedly came into the booth, took my decibel reader, made a reading, and refused to leave until I had turned it up to the unreasonably loud level he wanted. You do not have to handle things by yourself.

Option #5: Accept defeat

So you’ve shouted into the tour manager’s ear five times that you are not compressing the DJ mixes, the DJs themselves are triggering the speakers’ compression because their gain is so high. You’ve even shown him that you don’t even have the soundboard’s compressor enabled. But he’s still explaining to you that it’s your fault. At this point, it’s time to get a coworker to come over and repeat the exact same thing because repeating yourself into oblivion is an extremely inefficient way to get things done and irritating on all sides.

So you’ve shouted into the tour manager’s ear five times that you are not compressing the DJ mixes, the DJs themselves are triggering the speakers’ compression because their gain is so high. You’ve even shown him that you don’t even have the soundboard’s compressor enabled. But he’s still explaining to you that it’s your fault. At this point, it’s time to get a coworker to come over and repeat the exact same thing because repeating yourself into oblivion is an extremely inefficient way to get things done and irritating on all sides.

Unfortunately, sometimes it becomes clear that you will not get anywhere with a specific person. Whether they won’t let you get a word in, won’t listen to the words you are telling them, or act like you don’t exist, nothing is going to give. In this case, I find it useful to find a third person (at least older than me, usually male) to let my communication flow through, which is annoying is necessary to get things done first try. Obviously, this is my least favorite option, but it’s important to know when to cut your losses.