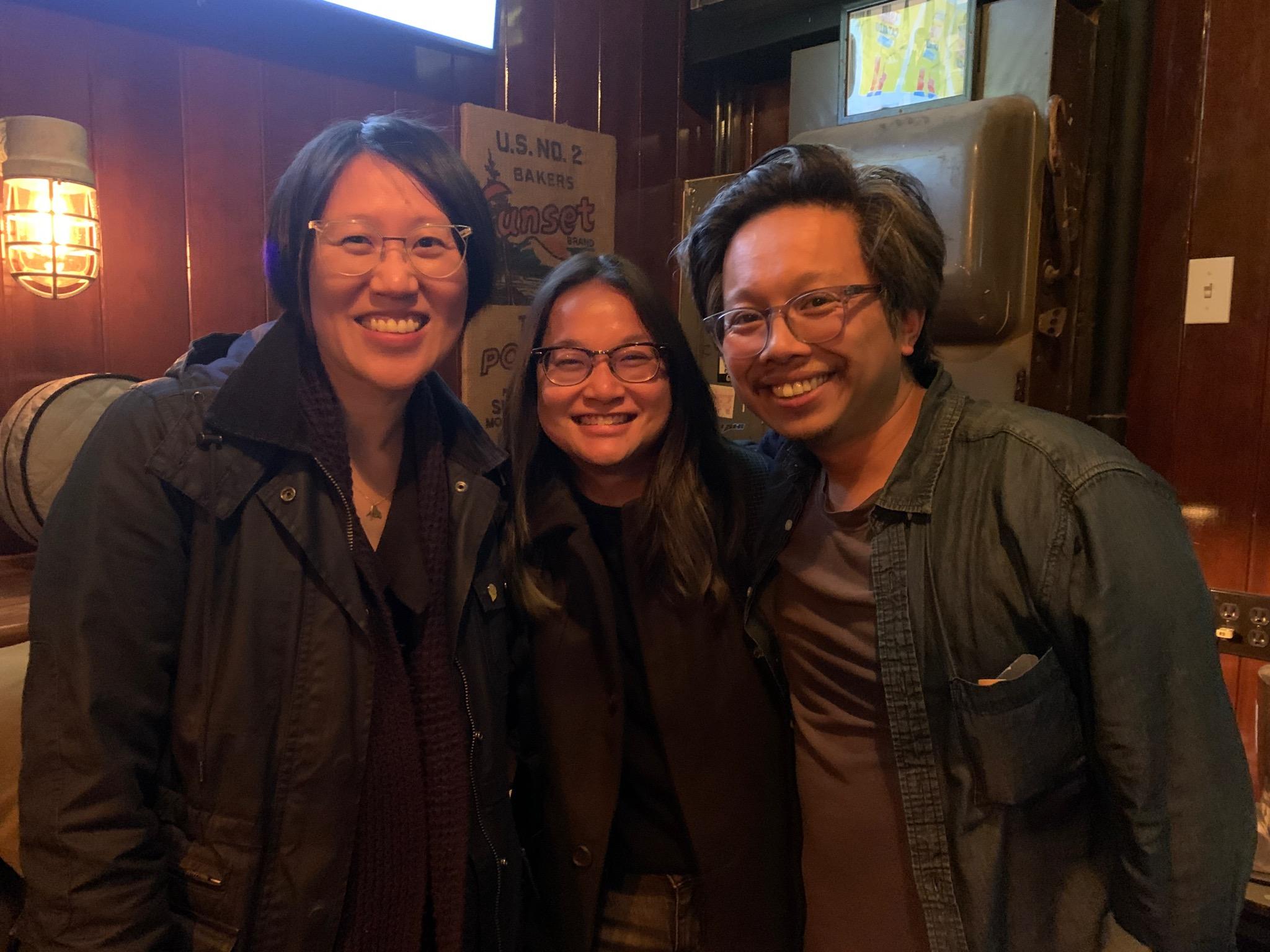

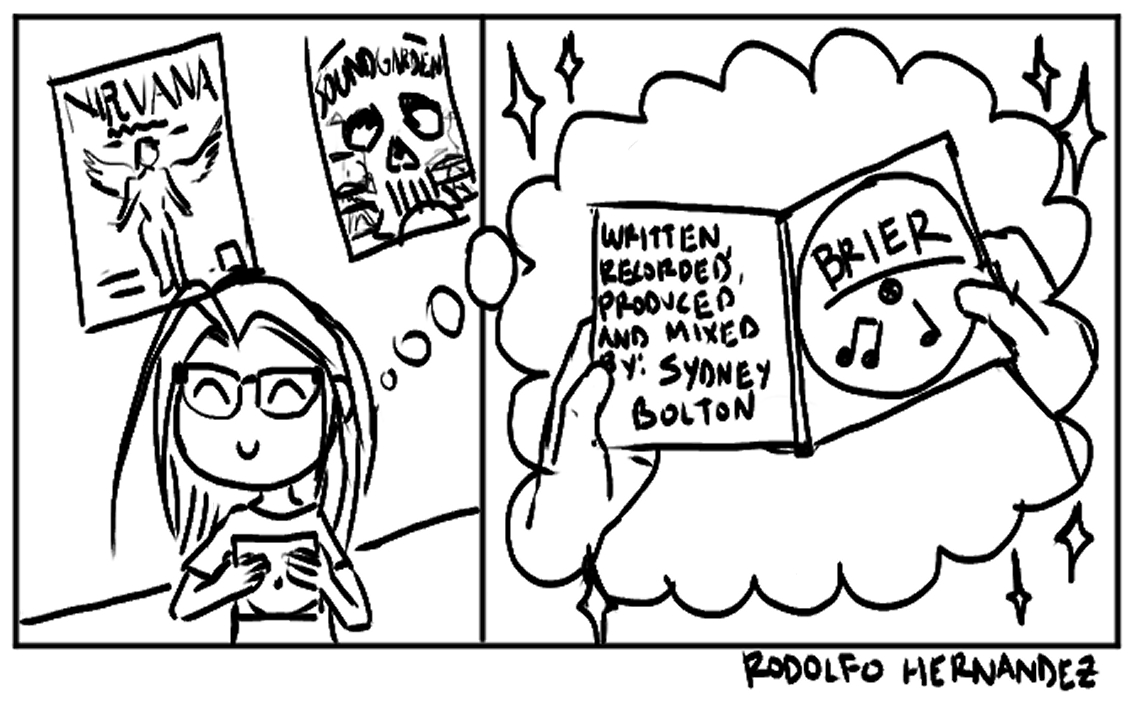

Sydney Bolton Live Sound Engineer, Production Manager and Translator

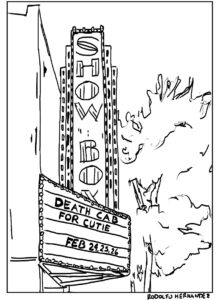

Sydney is a freelance live sound engineer working out of the great Northwest. Working in live sound since 2012 and works for the Showbox / Showbox SoDo, Morgan Sound, Carlson Audio Systems, and The Triple Door. She will be heading out on the road this fall with Gaslight Anthem as their monitor engineer.

Sydney’s interest in audio was sparked during her middle school years when she was recommended to The Vera Project in Seattle. The Vera Project is a DIY project that offers classes in audio, lighting, and studio recording and allows participants to volunteer to work their shows. Sydney says she was “always really interested in music. I actually thought I would become a musician and play in bands, I never thought I’d end up doing audio. When I was a kid I was really interested in how movies were made, and wanted to work in special effects for a while, so as I got older and started going to concerts that interest shifted to what goes into putting on a show and No one wanted to form a band with me, so I figured audio was the next best thing.”

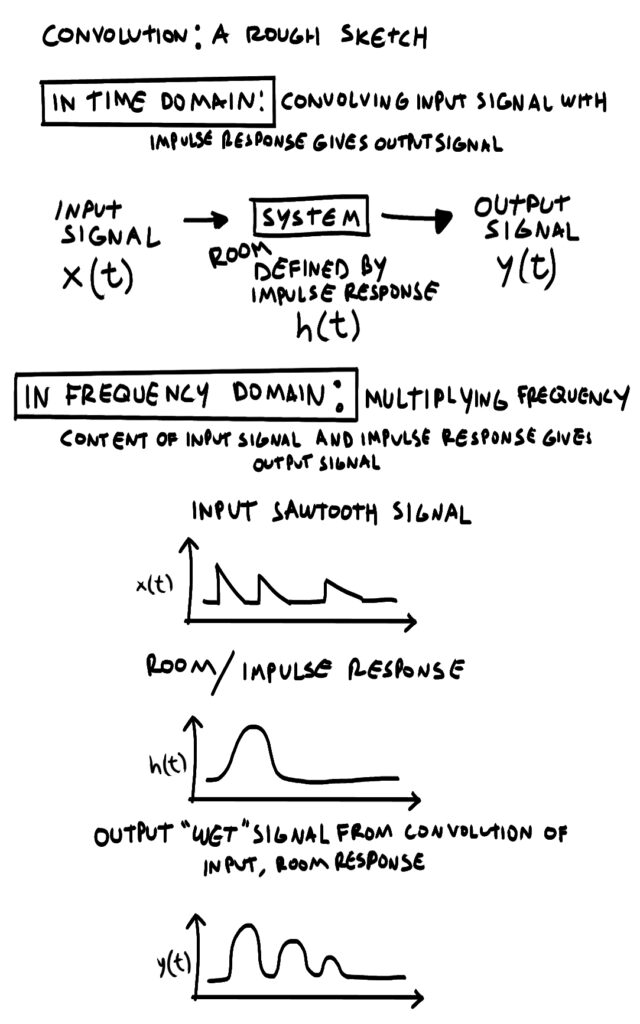

Sydney volunteered with the Vera Project for about a year and a half before being hired full-time. At the same time, she attended the University of Washington and graduate with a degree in Electrical Engineering (focus in DSP).

CAREER START

How did you get your start?

I got my start at a DIY venue called The VERA Project in 2012, and I worked there from 2012-2016. I was a volunteer for about a year and a half before getting hired by their FOH staff.

How did your early internships or jobs help build a foundation for where you are now?

I was fortunate enough to join The VERA Project when there was a full staff of experienced engineers working at other venues, and it was those connections that really helped build the start of my career and get me outside gigs, especially once I turned 21 and was able to work in bars.

What did you learn interning or on your early gigs?

I learned a lot. I think the main thing I learned was to have confidence in myself and my skills because I was a high schooler in charge of running shows on my own. I got very used to being underestimated and doubted and learned to ignore people’s misconceptions of me. I developed strategies to deal with people that were being judgmental and ignorant and also learned the importance of letting the people that did accept me right away know how meaningful that was.

Did you have a mentor or someone that really helped you?

I would say I’ve had a few throughout the different stages of my career.

Back at The VERA Project, there was one engineer in particular named Chris Gibbs who did a lot to get me to the point where I could take shows on my own. He was also responsible for throwing me a lot of the first gigs I got outside of The VERA Project as I started to outgrow it.

Kelly Berry took a chance on me while I was still in high school and working for his small audio company was my first introduction to production work. Josh Penner, Robin Kibble, Alejandro Irragori, and Ryan Murgatroyd have all been very supportive and helpful with navigating the touring side of things.

More recently, I credit Josh Wriggle with seeing my potential as a production manager, convincing me to give it a try, arguing with the right people to make it happen, and mentoring me through the whole process. Aside from production managing the occasional Showbox show I also production manage at a smaller venue and take occasional production assistant work.

CAREER NOW

What is a typical day like?

It varies a lot depending on what job and venue.

On a typical day doing venue sound, I’ll show up and we’ll load in the tour, and get them set up. When they’re ready to soundcheck I’ll hand over drive lines and open up the PA. About half the time, especially at the larger venues I work at, the tour will be mostly or completely self-contained and that is pretty much all I have to do until load-out. If I do get to mix, I’ll talk to the support when they arrive, double-check that the input lists and stage plots we got are accurate, find out if they have any specific mix notes for me or any other requests, prep everything for soundcheck so that we can just throw and go. One of the main venues I work at has a 5:00 PM noise curfew most days, so usually opener soundchecks are pretty rushed – we are lucky if we get half an hour.

Working for production companies is obviously very different since you don’t have a system to walk into and sometimes the builds are very big. Usually, we’ll show up, dump the trucks, more often than not wait for the staging company to finish building the stage. From there we organize which cases go where and layout power, audio, build towers if needed, and fly PA. I am usually patch, so once the PA is in the air I get to work laying out everything that goes on the stage – placing subsnakes, coming up with a patch plan for all of the acts, micing everything, having a plan for changeovers, making sure the A1s know the input list. Then we do the show, take everything down, get it all back in the cases, and get the cases back in the trucks.

Production managing is very different. Hopefully, the tour has gotten back to me and I have all the information I need, but that’s not always the case. I usually show up a couple of hours before venue access, in case the tour arrives early and also so I have time to print and set out day sheets, give the shopper plenty of time to get hospitality shopped, tidy up the green rooms, etc. I like to hand over any cash to the tour first thing so that I don’t have to think about it, and if there’s a runner I introduce them to the tour manager as soon as possible. After the security meeting before doors, the rest of the day is managing parking, scanning in receipts and filling out paperwork, refilling the tour’s ice, and dealing with whatever problems arise. At the end of the night, I introduce the tour manager to our house manager to settle, help clean out the green rooms once the tour has left, and head home.

How do you stay organized and focused?

When it comes to scheduling, I use a digital calendar but also have a paper one hanging by my door that I write all of my workdays and call times into. I know my limits and try to avoid working more than 5 days in a row, and I also try to keep one regular weekday off (usually Mondays) and at least one weekend day off each month. It helps keep me sane – that I can have a little bit of regularity to my schedule, and I know that there’s at least one day when my schedule will match up with friends who work regular jobs.

What do you enjoy the most about your job?

I am the happiest on days when I get a mix dialed in that I feel proud of, on the days that I do sound for friends’ bands, and on days when I get to work with bands that I am a fan of. Those are the days that remind me why I do this. I also appreciate the huge variety of music that I get to work with – I’ve been introduced to genres that I didn’t know existed and found out about so many great artists through work. Even if it’s not music that I personally like, enough other people like it enough to show up and keep me employed that night. When I can’t appreciate that anymore it will be time to find another job.

What do you like least?

I don’t like that no matter how tired you are, how far away you’ve come from for that gig, or how injured or sick you are, there’s probably someone that had even less sleep than you, that came from even farther away to get there, that hurts more or feels worse than you. That’s the side of our industry that I don’t like.

What are your long-term goals?

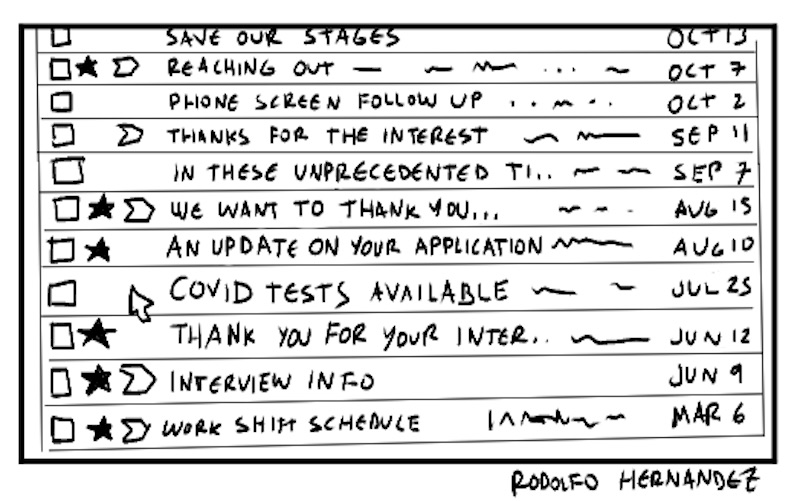

I want to tour. I was really close before the pandemic, and have had many near misses since things reopened, but it just hasn’t worked out yet.

What if any obstacles or barriers have you faced? How have you dealt with them?

I’ve dealt with the usual misogyny that most women in this industry will face at some point, and I’ve written for SoundGirls in the past about experiencing racism for the first time. There are venues in town that I know I can’t work at if I want to be treated well and paid the same, and that’s frustrating but you just have to work around it. I’ve noticed too that lately it’s taken coming across some of the few other Asian people in this industry to find people willing to go out of their way to support me and give me opportunities, and while the solidarity is nice it’s frustrating that my career seems to hinge on it.

Mostly I just try to let it roll off of me. As I said above, I think confidence is key. I know that I’m a good tech and that the right opportunities for me will come along. Finding the people who support you and stand up for you, and keep them close by is also really important. I feel like I have gotten to the point where I have a really solid group of people around me, that has made a huge difference in how I feel at and about work.

But if it bothers you too much and you don’t want to put up with all of it, that’s totally valid too. I know that I have thought about quitting many times. In the end, I like my job and the people I work with too much, but that might not apply to everyone. It can be hard sometimes.

Advice you have for other women who wish to enter the field?

Be confident in yourself first and foremost. Until you get to venues big enough to have a separate monitor position you won’t have anyone to back you up or help troubleshoot, and there will be many times where you will need to stand up for yourself and trust in your skills.

Find the people that want to help you succeed and stick with them. Always say thank you. And once you get to a point where you can help others, try to create opportunities for those below you.

Also, don’t be afraid to turn down gigs or walk away from places that aren’t treating you well. If you are good at what you do, there will always be more work. There is a lot of pressure to say yes to everything, especially when you’re first starting out, but you don’t have to.

Must have skills?

You absolutely have to be able to keep calm under pressure. We spend a lot of time in hurry-up and wait mode but do enough shows and you will have one that goes catastrophically wrong.

You also shouldn’t be afraid to ask questions and own your mistakes. No one starts off knowing everything, and mistakes are part of learning.

Be someone that people like to work with. Technical knowledge can always be learned, but being someone that is on time and pleasant to be around will get you much farther.

Favorite gear?

I’m mostly on DiGiCos these days, and we’ve got Quantums at my main places of work. I got to try out nodal processing for the first time the other day when mixing monitors and it was pretty cool.

Translator

Knowing other languages can be surprisingly helpful too. During the pandemic, I revised Spanish translations for the plugin company Goodhertz and translated a new plugin into Spanish from scratch, which is a job I never knew existed. I speak several languages and I find it an excellent way to win over international crews (and it can also make facilitating communication much easier).