BREAKING IT DOWN

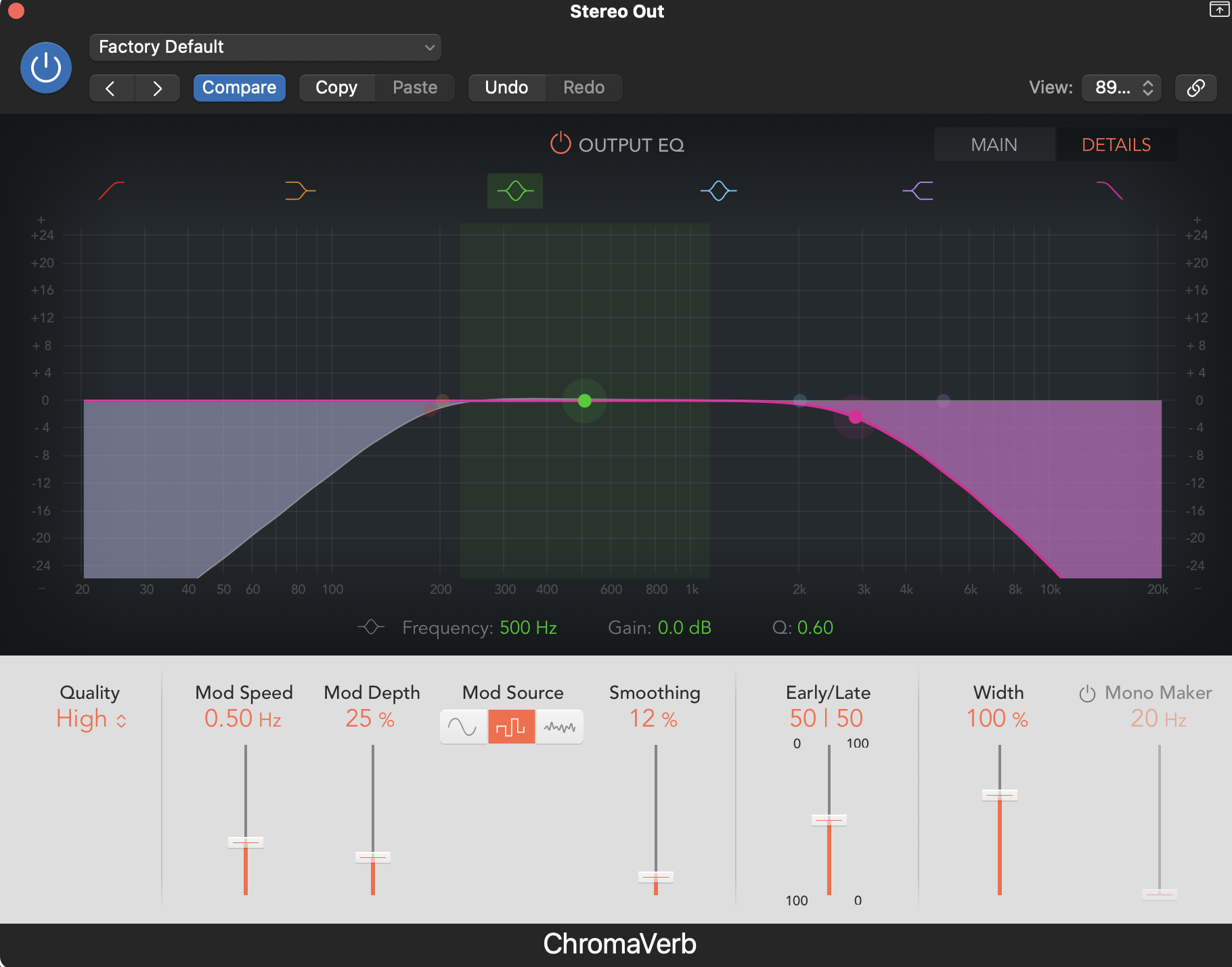

EQ

It is the mixer’s job to EQ effects if they are coming from behind a door, are on a television screen, etc. Basically, anything where all elements should be futzed for any reason. If this is the case, do your mixer a favor and ask ahead of time if he/she would like you to split those FX out onto “Futz FX” tracks. You’ll totally win brownie points just for asking. It is important not to do the actual processing in the SFX editorial, as the mixer may want to alter the amount of “futz” that is applied to achieve maximum clarity, depending on what is happening in the rest of the mix.

It is the sound designer’s job to EQ SFX if any particular elements have too much/too little of any frequency to be appropriate for what’s happening on screen. Do not ever assume that your mixer is going to listen to every single element you cut in a build, and then individually EQ them to make them sound better. That’s your job! Or, better yet, don’t choose crappy SFX in the first place!

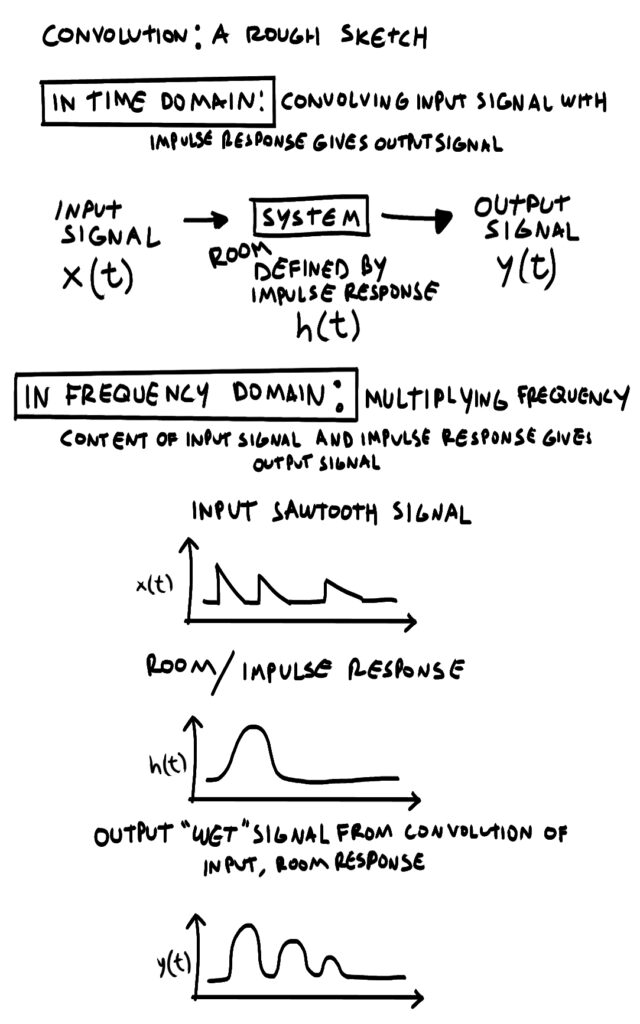

REVERB/DELAY

It is the mixer’s job to add reverb or delay to all sound effects when appropriate in order to help them to sit within the physical space shown on screen. For example, he or she may add a bit of reverb to all sound effects which occur while the characters on screen are walking through an underground cave. Or, he or she may add a bit of reverb and delay to all sound effects when we’re in a narrow but tall canyon. The mixer would probably choose not to add reverb or delay to any sound effects that occur while a scene plays out in a small closet.

As a sound designer, you should be extremely wary of adding reverb to almost any sound effect. If you are doing so to help sell that it is occurring in the physical space, check with your mixer first. Chances are, he or she would rather have full control by adding the reverb themselves.

Sound designers should also use delay fairly sparingly. This is only a good choice if it is truly a design choice, not a spatial one. For example, if you are designing a futuristic laser gun blast, you may want to add a very short delay to the sound you’re designing purely for design purposes.

When deciding whether or not to add reverb or delay, always ask yourself whether it is a design choice or a spatial choice. As long as the reverb/delay has absolutely nothing to do with where the sound effect is occurring, you’re probably in the clear. But, you may still want to supply a muted version without the effect in the track below, just in case, your mixer finds that the affected one does not play well in the mix.

COMPRESSORS/LIMITERS

Adding compressors or limiters should be the mixer’s job 99% of the time.

The only instance in which I have ever used dynamics processing in my editorial was when a client asked to trigger a pulsing sound effect whenever a particular character spoke (there was a visual pulsing to match). I used a side chain and gate to do this, but first I had an extensive conversation with my mixer about if he would rather I did this and gave him the tracks, or if he would prefer to set it up himself. If you are gating any sound effects purely to clean them up, then my recommendation would be to just find a better sound.

PITCH SHIFTING

A mixer does not often pitch shift sound effects unless a client specifically asks that he or she do so.

Thus, pitch shifting almost always falls on the shoulders of the sound designer. This is because when it comes to sound effects, changing the pitch is almost always a design choice rather than a balance/spatial choice.

MODULATION

A mixer will use modulation effects when processing dialogue sometimes, but it is very uncommon for them to dig into sound effects to use this type of processing.

Most often this type of processing is done purely for design purposes, and thus lands in the wheelhouse of the sound designer. You should never design something with unprocessed elements, assuming that your mixer will go in and process everything so that it sounds cooler. It’s the designer’s job to make all of the elements as appropriate as possible to what is on the screen. So, go ahead and modulate away!

NOISE REDUCTION

Mixers will often employ noise reduction plugins to clean up noisy sounds. But, this should never be the case with sound effects, since you should be cutting pristine SFX in the first place.

In short, neither of you should be using noise reduction plugins. If you find yourself reaching for RX while editing sound effects, you should instead reach for a better sound! If you’re dead set on using something that, say, you recorded yourself and is just too perfect to pass up but incredibly noisy, then by all means process it with noise reduction software. Never assume that your mixer will do this for you. There’s a much better chance that the offending sound effect will simply be muted in the mix.